Released in 1948, Rope remains one of Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest technical achievements. Initially intended as a “stunt”, the film was a triumphant experiment in innovative recording techniques. Hitchcock modernised several cinematic processes, challenging the basic principles of editing while encouraging others to do the same. It was a significant evolutionary stepping stone for the director.

A piercing scream leads us into a penthouse apartment. Inside, we voyeuristically observe Brandon (John Dall) and Philip (Farley Granger) strangling their friend, David. The pair believes their social and academic superiority will allow them to get away with the crime, confidently hiding David’s body in a wooden chest, around which a party is about to take place. Yet their cool exteriors soon crack, when their college professor (James Stewart), begins to question them.

Based on Patrick Hamilton’s 1929 play, Rope took inspiration from Leopold and Loeb, two affluent students who murdered a child to validate their intellect. The story captured the snobbery of 20th century high society, of pre-yuppie socialites and academic segregation. It borrowed from American hard-boiled fiction, where urban violence was traditionally used to condemn the hierarchy. With Rope, Hitchcock bought into this social finger-pointing, openly criticising the upper classes, and simultaneously denouncing an entire fan base.

Hitchcock was fascinated by the Aristotelian Unities, and since his film was based on a play, he seized the opportunity to shoot Rope in real time – a daring cinematic first. Rope explored the relationship between time, space and action, reinventing established recording concepts with long takes, another industry first. Hitchcock was able to create a traditional drama for the modern age. Early films were made up of hundreds of shots, each lasting between five and 15 seconds. While 1963’s The Birds was constructed from 1,360 shots, Rope required just 10. Each scene ran for the full length of a film reel: 10 minutes. To counteract the necessary cuts, whenever the reel needed changing the cameraman would close in on blank surfaces, beginning the next reel with an identical shot thus imitating continuity.

To accomplish this, cameras were placed on dollies. The set was fully mobile – even the faux clouds moved across the skyline. These complex mechanics took place silently, since the soundtrack was recorded directly. Equipment was placed on special lubricated surfaces, to minimise noise. The notion of recording live dialogue was entirely unthinkable in mid-20th century cinema, but Hitchcock accomplished it with masterful resolve.

In 1948, Hitchcock gave way to modernity, and Rope became his first colour film. Though initially hesitant, Hitchcock eventually settled for a diluted colour palette, which neither improves nor impairs the film. Shooting in colour proved problematic, since the action of the film began in daylight and ended at dusk. The skyline backdrop was carefully controlled to reflect the changing hours. The entire film was carefully planned and meticulously executed, like a military operation.

With Rope, Hitchcock threw out the rule book and left a new blueprint for future filmmakers. The film provided so many industry firsts that Hollywood began to fundamentally question the entire process of making movies. Rope is an astonishing feat of cinematic engineering – a pivotal piece of work that demonstrated Hitchcock’s meticulous pursuit of authenticity and his ability to redefine an entire art form.

Published 29 Apr 2016

By Ivan Radford

The director’s deep affection for his home city can be felt throughout his revered body of work.

By Adam Cook

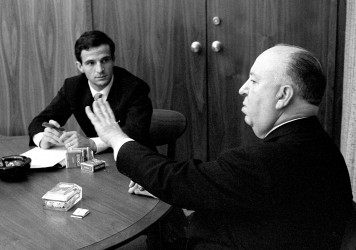

Two grand masters come head to head in this insightful documentary from film critic Kent Jones.

By Tom Graham

Twenty five years on from his death, the novelist famed for his film noir screenplays remains a key influence.