Taken from the Japanese word for ‘turmoil’, Ran unfolds slowly over the best part of three hours. Its story is grand but its plot is relatively simple. It is Akira Kurosawa’s epic retelling of William Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’, interwoven with the history of Japan’s 16th century Civil Wars and the legend of Morikawa, a feudal warlord who had three sons as opposed to Lear’s three daughters. Hidetora, the Lear figure, gives up his power and divides his kingdom among his progeny. Turmoil ensues.

In its newly restored 4k format, Ran is returning to cinemas this month to coincide with Shakespeare’s 400th anniversary. It is Kurosawa’s final masterpiece, a stunning meditation on mankind’s capacity for relentless destruction made by a 75-year old director who had come to feel profoundly troubled by the world around him, had tried to kill himself a decade earlier and who was struggling to finance his films.

“Man is born crying. When he has cried enough, he dies,” observes Kyoami, the fool. Like his Shakespearean counterpart, he remains by his king’s side and has all the best lines. A kind of distressed nihilism runs through the film. Walking through a landscape of ash and smoke, Kyoami’s master Hidetora, old and stricken, turns to him and says, “I am lost”. “Such is the human condition,” comes Kyoami’s reply. It’s a serious line but also one of the film’s few jokes.

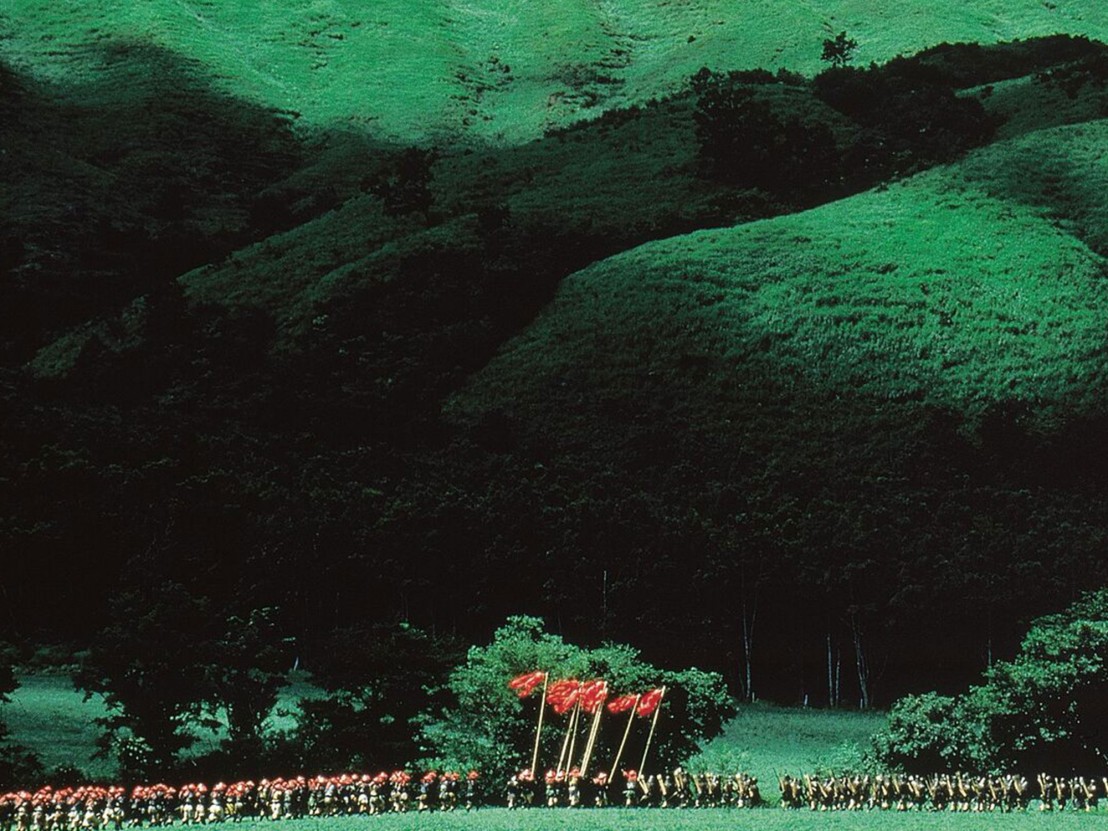

These observations sit perfectly within the epic framework of the film. With a budget of $12 million, Ran was Kurosawa’s most expensive film and was, at the time, the most expensive Japanese movie ever made. Every aspect of the film is grand: the ideas, the emotions, the aesthetic and even the movement of the actors, which is pronounced and deliberate, indicative of some overriding trait possessed by the character they are playing.

It is also a film unafraid to deal with the kinds of questions historic writers since Homer have grappled with, particularly humanity’s seemingly endless capacity for self-destruction. This could easily have led to a ponderous, pompous or simply flat piece of work. Modern day blockbusters, many of which owe so much to Ran, so often fall into this trap. They have all the visual grandeur without the intellectual weight.

Ran has Shakespeare at its source and is driven not just by the staggering beauty of its images but by the all-encompassing tragedy of its story. There is no easy get-out for the viewer either, no reassuring salvation. The amorality of the film reflects the amorality of life. We don’t leave the cinema feeling like we’ve been given a nice comforting shot of cultural opium, but instead staring into the dark heart of humanity.

By the mid-’80s, Kurosawa was practically blind. A painter before he turned filmmaker, the Japanese auteur drew and painted thousands of images to show his team what he wanted Ran to look like. This process transfers to the experience of watching the film, which at times feels closer to perusing traditional Japanese painting or European impressionists and expressionists in the ever-moving halls of a gallery. This experience recalls, in its more pastoral, European moments, Kubrick’s compositions in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. In the battle scenes, the colour, smoke, scale and weaponry are reminiscent of director Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo.

For the warriors of Ran, there is the hope of some kind of glory in battle, followed by an honourable death, though a devastating twist calls this into question, acting like a punch to the stomach. The fate of those outside the army is suggested by Tsurumaru, a character who has been left blind and alone by Hidetora’s warmongering. He has long hair and delicate features. He is vulnerable, as we all are, to the devastation of the world around us. Shorn of his final protection, a picture of the Buddha, we last see him teetering on the edge of a precipice. In this world, we are alone, we cannot see. The Buddha has no place in these lands.

Ran is released in the UK on 1 April and will be available on DVD and Blu-ray from 2 May. To find out where the film is screening near you visit independentcinemaoffice.org.uk

Published 23 Mar 2016

By Adam Cook

Nagisa Oshima’s 1968 film Death by Hanging is now available courtesy of The Criterion Collection.

If you liked The Hateful Eight you’ll love Sergio Corbucci’s 1968 film that inspired it.