Slowly casting off their association with dense and inaccessible art cinema, subtitles have become the translation norm for Western audiences. Yet sometimes the most powerful subtitles are the ones that aren’t there.

Leaving non-English dialogue untranslated has long been a way to ‘Other’ certain characters and cultures, damning them to irrelevance or impenetrability. For example, as the western genre has sought to eulogise the mission of white settlers, for a long time Native American characters were rarely, if ever, translated (when Native languages were used – often it was gibberish, or even English dialogue played backwards). Yet this allowed room for subversion, too. As chronicled by the 2009 documentary Reel Injun, some Native American actors, knowing that the filmmakers wouldn’t bother to subtitle their dialogue, turned their lines into jokes and insults that allowed them to take revenge on the film even as it stereotyped them.

Similarly, when graffiti artists were hired to dress a set in Arabic script for Homeland they wrote ‘Homeland is racist’, hiding a protest against the show’s negative depiction of the Middle East in plain sight. The fact that this story only broke once the episode had aired shows how little care the producers took with the show’s translations. Yet it also demonstrates that untranslated language is not always in the control of filmmakers, particularly when it is used only as part of an orientalist visual style.

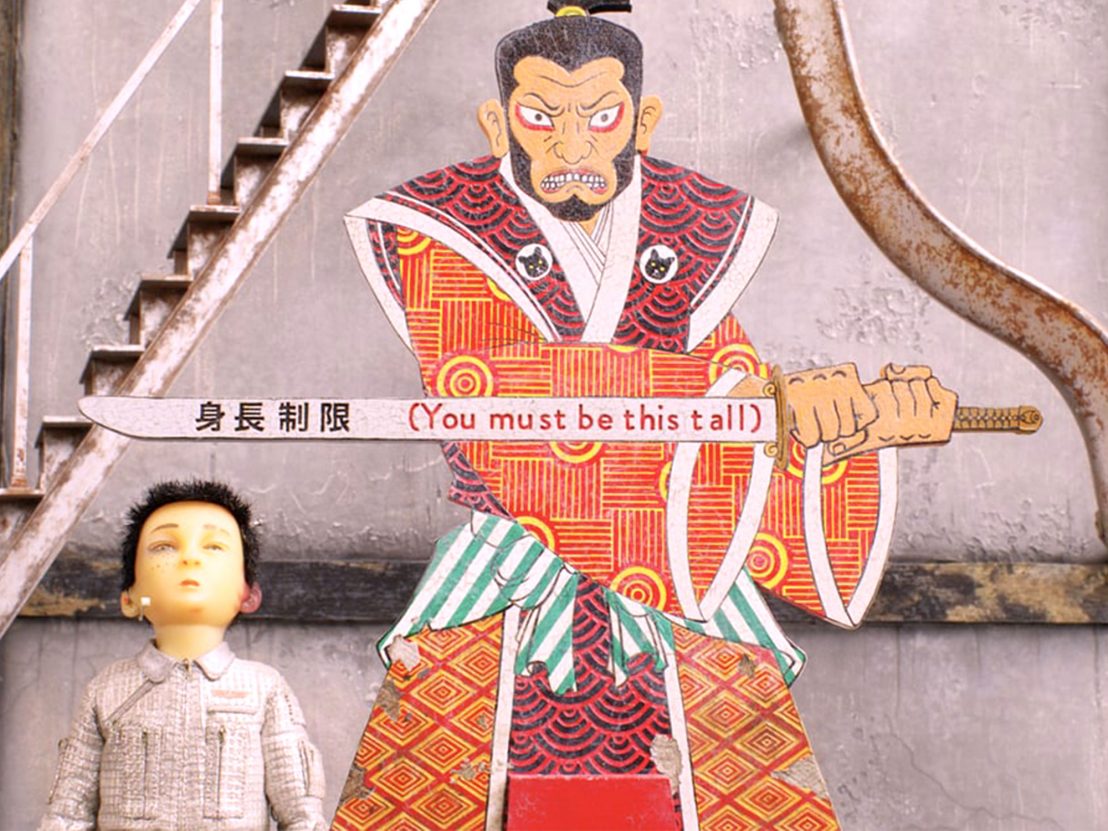

This was the criticism levelled at Wes Anderson after he left the bulk of the Japanese dialogue in Isle of Dogs unsubtitled (though it is often translated by other means). Similarly, David Lowery’s A Ghost Story subtitles its ghosts’ silent dialogue but not the Spanish of minor Latino characters. The effect of these choices remains hotly contested – at the very least, it indicates that we can never assume a single viewing experience. Skipping translation does not mean that those words are not understood – it just means that they are not understood by everyone. Of course, incongruous subtitles can provide humour, as in Annie Hall and the infamous scene from Downfall that’s become one of the internet’s most enduring jokes.

Recent science-fiction cinema posits a future that elides translation in a different way. In 2017, both Ghost in the Shell and Blade Runner 2049 featured English-speaking protagonists explore a multilingual city with ease – they understand dialogue in languages they never speak, suggesting that either technological advancement or naturalised linguistic diversity has eliminated the need for translation. Yet these moments are rare enough to feel tokenistic, and they ignore the fact that translation is a necessary part of multilingualism. Cutting out the process of translation is simply one way to dispense with the issue altogether.

Both of those films heavily display the Asian signage that is a mainstay of futuristic urban landscapes, but the dialogue is still mostly in English. Also released in 2017, Valerian is set in a city that boasts over 5,000 languages, yet English is practically the only human language we hear. Meanwhile 2005’s Firefly, set in the 26th century, features Mandarin exclusively for the untranslated profanities of its otherwise English-speaking characters; we meet next to no Chinese people. It seems the humans who go into space are selective in the languages they take with them.

But not all missing subtitles are simply deference to the supremacy of English. Kelly Reichardt’s 2010 western Meek’s Cutoff, set in 1845, follows a group of white settlers traversing the Oregon desert who along the way capture a Cayuse Native American – only credited as ‘The Indian’. They don’t share a common tongue, and his dialogue is not subtitled, so it’s not clear to us or them if he will lead them to water or to an ambush.

The Indian is no simple stereotype. Rather, his presence highlights the discord between the settlers and the land – his home – that they have charged into. As they try to guess his intentions, they are clearly drawing upon their own hopes, fears, and prejudices. Blowhard guide Stephen Meek advocates protectionist violence, whereas Michelle Williams’ pragmatic Emily Tetherow wants to cultivate trust with the stranger. Their fractured power struggle is far more intractable than a mere language barrier. In fact, Meek’s Cutoff is a film about invaders struggling to understand all sorts of signs in the unforgiving landscape where they become lost.

Moreover, the characters’ communication is marked by differences other than language. It is repeatedly the men who gather and make plans, while the women keep their distance and make guesses as to the conversation. For the women in particular it’s clear that all of Meek’s macho discourse is a sign not of his knowledge but of a vain, blustering ignorance. And they all believe that the language of trade and barter has a universality that will see them through – Emily even decides to help the Indian only because, as she says, “I want him to owe me something”. They are hopelessly unprepared for their mission, and highlighting the difficulties in translation only serves to make this clear.

Perhaps the most radical recent example of non-translation is 2014’s The Tribe, a film about criminal enterprise at a boarding school for the deaf. The dialogue is entirely in unsubtitled Ukranian sign language. It’s an audacious move, particularly given the already difficult subject matter, yet The Tribe succeeds with a startling structure and visual design. There is no musical score and only 34 shots, all of them wide, with no close-ups or inserts that might obscure the action.

This austere style makes for uncomfortable and at times harrowing viewing – we are, in the absence of aural dialogue, compelled to fix our gaze. Omitting translation lays bare the essence of communication: we all try to capture what we can of what’s being said, all according to our own biases, experiences, company, and viewpoint. Of course, the story can be gleaned without subtitles, but the nuance depends on the audience.

The point isn’t that translation is unimportant, but that it is multifaceted, complex, and never objective. This fact is overlooked by subtitles that are built to be as undisruptive as possible. Yet every aspect of a film’s construction is a sort of translation: the way a character is shot, how that shot is cut, and the accompanying music all transfer as much meaning as words spelling out their dialogue.

Linguistic diversity is a part of life, whether it’s navigating a dozen languages in the course of a day or mediating between different generations. Indeed, when it comes to how people actually communicate day to day, the boundaries between different languages, gestures, signs, or behaviour are not as firm as they might first appear. We all pick up these different tools as and when we need them, changing them in the process. And no form of language, be it Bengali, body language, or emojis, can resist the tides of change. Those films that use translation – or its absence – to challenge, involve or provoke the audience can help develop the capabilities of cinema to more intricately reflect how we all communicate, or fail to.

Published 21 Apr 2018

These bonus moments have become a mainstay of modern blockbuster. But are they a cynical marketing tool or cinema’s secret weapon?

This antiquated tradition could hold the key to ensuring the survival of smaller cinemas.

As streaming platforms vie with major film studios for viewers’ attention, great work is at risk of being lost in the content ether.