Earlier this week Ken Loach, promoting his new film I, Daniel Blake, levelled an attack at the BBC (and by extension the TV industry in Britain) by claiming that news coverage is rightwing and TV is too taken up with cosy, nostalgic period dramas that present a false and rosy view of history.

He’s right. Though there are pockets of resistance, the overall flavour of television and indeed cinema in Britain tends towards the conservative. Loach pointed the finger at Downton Abbey, but Poldark, Victoria, The Durrells in Corfu and War & Peace are just some of the other recent costumed entertainments he might well have named to make his point. Next up is The Crown, the new series by Stephen Daldry and Peter Morgan which retraces the early days of the courtship between Queen Elizabeth II and her husband, Prince Philip.

In film, recent period dramas about the establishment figures Stephen Hawking (Oxford) and Alan Turing (Cambridge) have starred Eddie Redmayne (Eton, Cambridge) and Benedict Cumberbatch (Eton, erm, Manchester), while A Royal Night Out, about the queen and Princess Margaret bunking off royal duties and having it large for an evening, was released last year.

If not all of these films and TV shows are cosy per se – the battle of Borodino was a bitch – their appeal still rests on presenting an image of the past that flatters modern sensibilities with ideas of past glamour and sophistication. Victoria presents a zingy and beautiful queen, against all evidence we have as to her character; Poldark gives us a completely banal look into a totally fantasised past in which the birth right and nobility of the aristocracy was self-evident and undisputed. If period dramas don’t all have to be ahistorical and cosy – and Loach himself has made three period dramas with a leftwing viewpoint on historical events, with more than their fair share of death and misery – it certainly seems that audiences are increasingly looking to be comforted in their concept of an idealised country.

How not to tie this into Brexit, and the false picture politicians presented of Britain when advocating for it? Audiences apparently don’t want to be reminded of unpalatable truths about the constitution of Britain, which has never been all white, never been peaceful, never fair.

Is Britain interested in reflecting its own political realities in fiction, onscreen? The problem isn’t merely that the working classes are seemingly out of favour now, both on screen and in drama and film schools – it’s that British minorities in general are having a hard time of it. Last week in an address to mark the start of the BFI’s Black Star season, David Oyelowo bemoaned the lack of opportunities for people of colour in British film – and it’s certainly true that he won’t be cast as AA Milne or Captain Wentworth any time soon. He, Idris Elba, Naomie Harris, Archie Panjabi, Thandie Newton and John Boyega are just some actors who have had to look to the United States for work. The BBC’s ambitious diversity and inclusion strategy, set out in April, is presumably still in its early stages.

The overall view isn’t totally miserable: Sally Wainwright’s Happy Valley presents working class lives, and particularly women, and Ordinary Lies, written by Daniel Brocklehurst, takes its cue from a vein of British social realism that Loach pioneered. The BBC mini-series Capital aimed to show a cross-section of society and in addressing the banking crisis took aim at a political issue of our time. This Is England ’90 bowed out just last year, more acclaimed than ever.

In the past few years, Under the Skin took a sideways look at working class Scotland, and – of all films – Paddington broached the subject of immigration. But what Loach correctly deplored, namely a lack of real engagement with current politics in Britain’s film and TV output, is hardly possible to deny. Will Britain’s parlous state prompt filmmakers to talk more about immigration, inequality, racism, poverty, or are we going to keep looking inward?

Published 21 Oct 2016

Ken Loach’s latest polemic has a vital message that’s diluted by some heavy-handed direction.

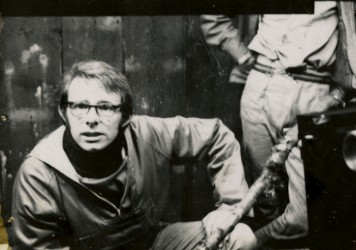

One of Britain’s most lauded and long-serving leftwing voices gets the whistlestop biog treatment.

By James Clarke

Land and Freedom shows the personal and political sides of this 80-year-old conflict.