Fifty years before Andrew McCarthy rode a motorcycle with Kim Cattrall clutching his waist, another department store model was experiencing the lifestyle of an A-list celebrity. No magic involved here – this is an all-too familiar Hollywood tale; overnight fame followed by an inevitable slump into obscurity. But this isn’t the story of a flesh-and-blood starlet.

Cynthia weighed 120-pounds, had freckles on her cheeks and was rarely seen without a cigarette in her hand and a vacant look in her eye. She commanded attention wherever she went, always with Lester Gaba at her side. Gaba worked as a soap sculpture before helping to revolutionise the mannequin design industry in 1936. Prior to this, models tended to be heavy and unwieldy, and had a habit of melting in warm weather. When department store B Altman and Company commissioned Gaba to make a series of mannequins based on a number of socialites, it was the beginning of what became known as the “Gaba Girls” phenomenon.

After this success, Saks Fifth Avenue wanted in on the action and a star was born – or rather made. Cynthia soon went from modelling clothes to attending the best shows, clubs and restaurants in New York City. She was gifted jewellery from Cartier and Tiffany, wore Dior and custom-made hats designed by Lilly Daché, and was even invited to the wedding of Wallis Simpson and the Duke of Windsor in 1937 (sadly, Netflix’s The Crown neglects to include this detail), although she didn’t attend the nuptials. She lived the sort of life Holly Golightly could only dream of.

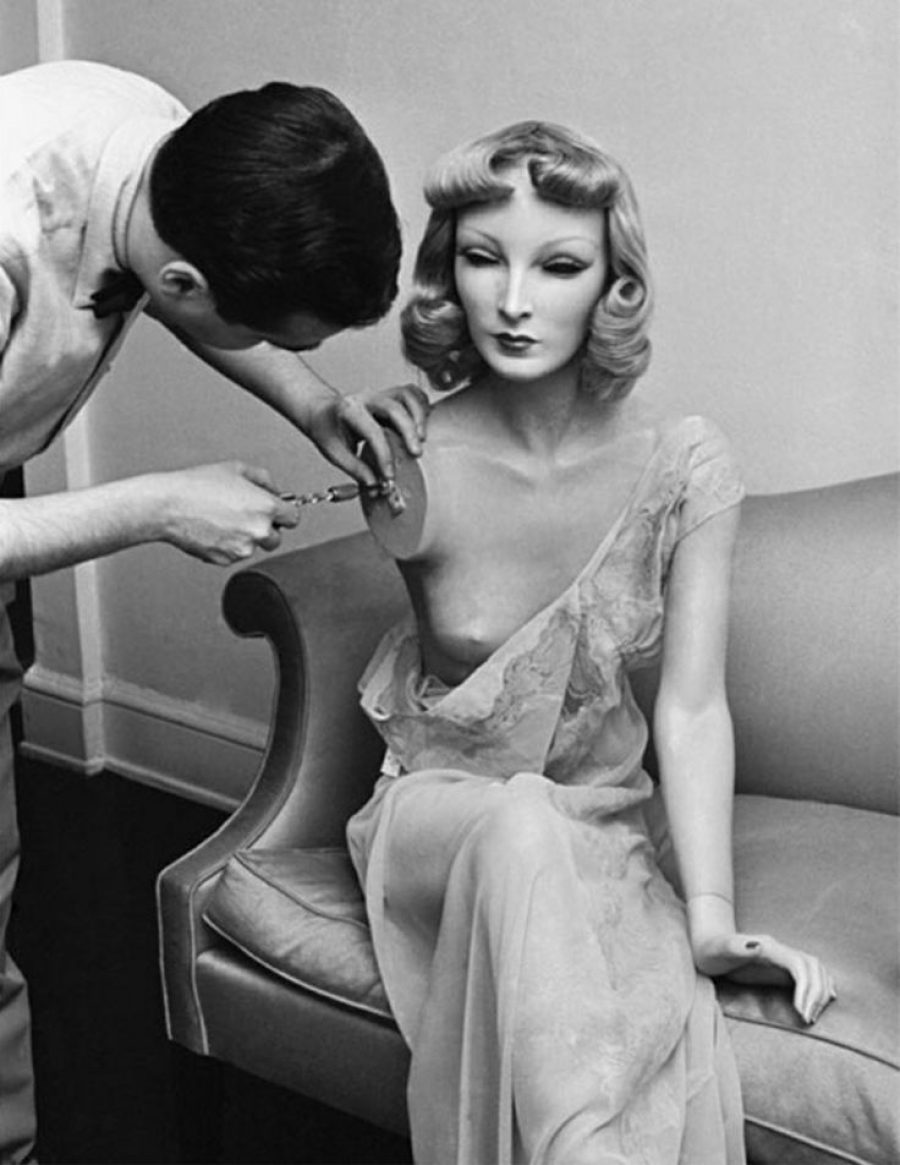

A Life magazine cover story beckoned; legendary photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt captured Cynthia in various states of undress and construction. One shot, showing her cloaked and bound, appears incredibly sinister, but this was really Gaba’s way of protecting his doll. The stark reality of Cynthia’s existence was not covered up. There was no protecting her modesty or pretending she wasn’t plaster and paint – even if Gaba sometimes blamed her lack of talking on laryngitis. Eisenstaedt photographed her getting a manicure, having her lipstick touched up, at brunch, in a bar and on a New York City tour bus checking out the sights with tourists. Cynthia: she’s just like us.

Timing is often just as important as talent, and Cynthia’s rise and fall is predicated on both these aspects. She was one of the first lifelike mannequins, and by treating her as though she were a living, breathing person, she ended up living the life of one. And like so many other models who have followed Cynthia’s path, she tried her hand at the movie business, appearing in the 1938 Jack Benny/Joan Bennett comedy Artists and Models Abroad. This was during Bennett’s blonde ingénue phase, where she played a rich girl wishing for a simpler life. Edith Head made Bennett’s costumes for the film, which was heavily marketed towards women with an interest in fashion – the type of women who almost certainly knew who Cynthia was.

Artists and Models Abroad plays on mistaken identity, but unlike the 1987 rom-com Mannequin, Cynthia doesn’t spring to life. Hiding out from the police in a theatre full of mannequins, the police officer pursuing Jack Benny’s character bops Cynthia on the head to see if she is real. The realistic dummy provides the perfect hide-in-plain-sight scenario.

Some are destined to spend decades basking in the limelight, but this wasn’t the case for Cynthia. First there was heartbreak after she slipped off a chair in a beauty salon and broke into pieces; her death was reported to the press. War came for Gaba as he was inducted into the US army in 1942. But this wasn’t the end for the world’s most famous mannequin. Hollywood is littered with comeback narratives and Gaba had something special planned for his star.

Despite the various changes the entertainment industry went through during and immediately after World War Two, Gaba was determined to aid Cynthia in this next stage of her career. In 1953 he spent $10,000 on modifications (equivalent to nearly $100,000 in today’s money) so that she could “speak” and move. He then sought out private investment and attempted to land a TV deal for this ‘living’ doll.

The former soap sculpture had turned to the medium that was now selling soap, but after 20 failed auditions, the rejection became too much. In a candid 1960 New York Times interview, Gaba offered an explanation as to why his endeavour failed: “Cynthia never made any sense. She muffed lines.” Alas, a gimmick only works as long as it sells.

Despite the close bond between creator and model (in the same interview Gaba recalls riding in a car with Cynthia and suddenly beginning to feel that she was a real person), their relationship eventually grew stale. “So one day,” Gaba confesses, “while absolutely disgusted, I took Cynthia down to the studio of a mad scientist in Greenwich Village and left her in the attic.” Not quite the same fate as your average fallen starlet, then, but this unceremonious dumping still rings true. Cynthia was a mannequin that became famous, but by 1960 the industry had turned to actresses for inspiration – real-life stars such as Audrey Hepburn, Brigitte Bardot, Anita Colby and Suzy Parker.

So where is Cynthia now? Gaba retired from the mannequin design business in 1962, keeping his fashion column for Women’s Wear Daily until 1967 and staging fashion shows thereafter. What became of Cynthia is a mystery, but for a brief period in the 1930s she was a genuine superstar. Her rise and fall were swift; the impact she left on the mannequin industry indelible. Should she ever resurface from some dusty Greenwich Village attic, she would be the perfect choice for the lead role in her own biopic. And she won’t have aged a day.

Published 18 Feb 2018

The Olympic figure skater turned actor was a huge celebrity in her day – but controversy was never far away.

Tale of Tales is a return to a much darker, more traditional form of fantasy storytelling.

Five Came Back reveals how a handful of famous directors went to war and came back changed.