Hungarian colossus Béla Tarr’s ‘last film’ is a magnificent, towering achievement.

Somewhat facetiously, and with tongue placed firmly in cheek, the Irish literary critic Vivian Mercier wrote that with ‘Waiting for Godot’, Samuel Beckett had ‘achieved a theoretical impossibility – a play in which nothing happens, that yet keeps audiences glued to their seats. What’s more, since the second act is a subtly different reprise of the first, he has written a play in which nothing happens, twice’.

What might he have made of The Turin Horse, the ninth theatrical feature from Hungarian colossus, Béla Tarr? Surely he’d admire the cyclical nature of a descent into darkness in which nothing happens, six times.

In much the same way that only a singularly gifted wordsmith such as Beckett could transform said nothingness into the most intoxicating of propositions, Tarr’s uncompromising formal control ensures that The Turin Horse remains nothing short of riveting.

Narratively stark and possessing an austerity of tone that eschews the absurdist moments of levity present in 2000’s Werckmeister Harmonies or his magnum opus from 2004, Sátántangó, this supposedly final film continues to explore such notions as the immutability of human nature, the futility of resistance against predetermination, and the inescapable stasis dealt by the cards of fate. These thematic preoccupations have long characterised Tarr’s work and are made especially bleak in this case by the defeating drudgery of survival that negates even the concept of hope.

A characteristically dazzling opening sequence sees a lame farmer driving his horse through a typhoon of Old Testament proportions. Later, we’re introduced to the farmer’s daughter and the oppressive routine of the pair’s daily chores, underscored by the recurring dirge of Mihály Vig’s string score.

With title cards announcing the passing of days, the same scenes recur with subtle but increasingly significant and monumental shifts in perspective. Close-ups of weathered faces reveal no trace of emotion. With conversation non-existent, character and relationships are divined through action; the few words between the pair are exchanged with perfunctory haste. A single scene with a passing neighbour, stopping by to share a glass of moonshine and some worldly wisdom, offers perhaps the one chance to read some higher purpose into these lives led without significance.

But beyond such sisyphean cycles of repetition, the father soon disavows any question of transcendence with a forcefully abrupt, “Come off it! That’s rubbish!” As the well dries up and the stubborn horse refuses to move, Tarr sinks the pair further towards the literal darkness that will finally envelop them.

Whether the cinematic rapture of the final moments are to be considered nihilistic or ecstatic – full of hope at man’s capacity for survival or weighed down in resignation at the ultimate pointlessness of existence – is a question for each viewer to decide for themselves.

Whichever way you look at it, though, if this does prove to be Tarr’s last film, one couldn’t ask for a more masterful, purely cinematic coda to this singular and most Beckettian filmmaker’s astonishing career.

Published 1 Jun 2012

A new film by Béla Tarr is the cinematic event of any year.

To misquote Woody Allen: “Potatoes... A lot of potatoes... A tremendous amount of potatoes.”

A magnificent, towering achievement.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s hypnotic metaphysical noir is towering, tough and very, very pretty.

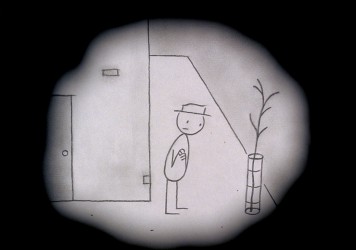

The first feature film from Austin-based animation powerhouse, Don Hertzfeldt, is a rapturous joy to behold.

Leonardo DiCaprio feels the wrath of man in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s awesomely violent revenge western.