Back in cinemas this week, Hideaki Anno’s feature-length finale breaks hearts, bodies, and the fourth wall.

Though the finality of its title would eventually become a misnomer, due to the new trilogy of ‘Rebuild of Evangelion’ films, The End of Evangelion is a mighty conclusion. Designed to replace the controversial final two episodes of Neon Genesis Evangelion, The End of Evangelion expands the series finale’s contemplation of emotional crutches and human connection to an apocalyptic scale.

A combination of scheduling and budget issues as well as Anno’s indecision around the ending lead to the show’s infamous finale, a pair of episodes that threw out the central conflict, instead opting for a metaphysical group therapy session taking place within its character’s minds, made with simplified drawings and various other rough materials. It was bizarre and abstract – almost photo-collage – and drew a lot of ire for that strangeness. While its production context is too complicated to summarise in brief here, the feature film The End of Evangelion was later made as a new ending for the show.

The show itself centres around Shinji Ikari, a teenager recruited by his absentee father Gendo in order to pilot a skyscraper-sized mech called an Evangelion (colloquially called an ‘Eva’) and fight the Angels, Eldtrich alien monsters that are attacking the city of Tokyo-3. Traumatised after being forced to kill a friend, Shinji is despondent.

It’s a finale that reduces its would-be hero to his lowest point within the first few minutes, and only keeps descending from there as his defeatist attitude finally screws things up beyond complete repair; it’s the harshest the series has ever been towards its protagonist, a sort of self-loathing present in Anno’s critique of otaku-dom as an emotional crutch.

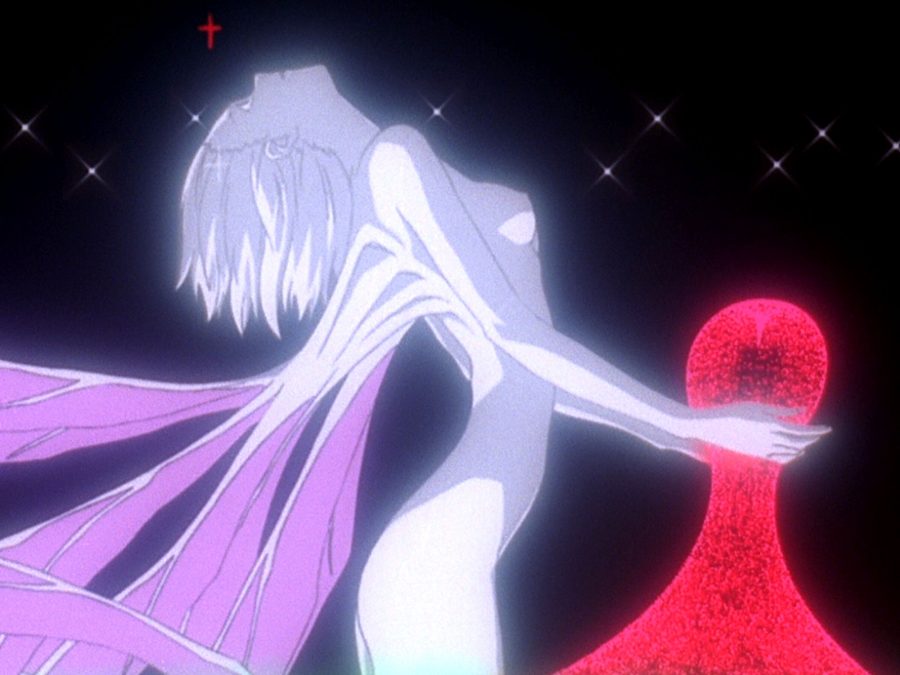

The End of Evangelion is reputed as a depressing and fatalistic film – but it’s far from it. Its emotional breakthrough is given vivid, thrilling form, told with more optimism than is often credited, even as the imagery becomes more and more hellish and macabre. It’s also simply incredible to look at, with bold splashes of colour in every frame, with nuanced movements from the humans and humanoid robots alike, with weight and detail in both its action and its quieter moments of drama.

That being said, this is still a film filled with plenty of action, and is among the finest Anno has ever directed. The final stand of Asuka, Shinji’s fellow Eva pilot, is particularly awesome – for all this writer’s talk about the psychological traumas of Evangelion, this is still a film in which a giant red robot roundhouse kicks a helicopter.

Yet some of the most astonishing moments in the film come from Anno revealing the artists’ hand behind the imagery, with a use of animatics and rough sketches mixed in its onslaught of montage. It even breaks the line between film and audience as it switches to live action, reflecting a cinema audience back at its viewer. The End of Evangelion draws attention to its own construction, “destroys itself” to reveal the emotional truths of its cast.

That extends to every element of the feature. Both Yoshiyuki Sadamoto’s character design and Ikuto Yamashita’s mechanical design are focused on human frailty; the mechs bleed and suffer in parallel to their pilots. That annihilation of the body in the film’s first half eventually moves onto the annihilation of the ego in the second, and then the aforementioned boundaries of animation itself.

Various onslaughts of montage gradually collapse each respective barrier in the film, until only the one between world Anno resides in and the world his characters reside in remains – and then that breaks too, in spectacular fashion. It’s the product of a marriage between Anno’s previous work in animation and his various genre influences, as well as the experimental sensibilities that he would further develop with his live-action work, finding peculiar angles through his use of digital handheld.

Still, even with its faster pacing, there’s no traditional third act throw down or grand reveal; just a boy being taught to believe that he might have a shot at being happy. Even as the Evangelion franchise has continued into remakes, the core of it has always been about what is rather poetically stated at its conclusion: changing yourself into someone better. The End of Evangelion is perhaps only vaguely hopeful, plenty has still been lost, perhaps permanently. But its characters have changed themselves, and progress is progress.

Published 10 Nov 2021

One of the most popular anime franchises ever, perhaps at its most daring.

Bewildering and genuinely very upsetting amidst its baroque, impeccably crafted spectacle…

…but also exciting, hopeful, nearly impeccably made. Congratulations!

The producers of Avatar prequel The Legend of Korra expand on Netflix’s dark fantasy series with a bloody “anime”.

The anime master behind Paprika and Perfect Blue left behind several incomplete projects which could still be realised.

Pyrokinetic mutants, shirtless firefighters and eco-fascists collide in the first feature film from Studio Trigger.