Juliette Binoche goes looking for love in this scintillating comedy-drama from French director Claire Denis.

A white backdrop stapled to a floor, filmed from a high angle; on it crouches Isabelle (Juliette Binoche), a Paris-based abstract painter. Brush and palette in hand, she begins to move around, filling in the space beneath her feet. The shot ingeniously positions Isabelle as author and subject. The canvas pulls double duty as her frame and ours. It offers a glimpse of a creative process that is serenely yet maddeningly enigmatic. Are these slow, languorous, black-on-white strokes planned, or extemporaneous? Or, put another way: does Isabelle already see the bigger picture, or is she just making it up as she goes along?

Let the Sunshine In is very much the proverbial portrait of the artist, as well as of an artistic community, marking the first time that director Claire Denis has explicitly dealt with creativity as a theme (not counting her documentary portraits of her mentor Jacques Rivette and choreographer Mathilde Monnier). It’s also, at least superficially, a romantic comedy, tracking Isabelle – who is 50, divorced, and sharing custody of a 10-year-old daughter – through a series of troubled relationships and sexual encounters with men in what is referred to insistently (by one of her suitors, a snide gallery owner played by Bruno Podalydes) as her “milieu”. The common denominator between her partners, who include a banker, an actor and a curator, as well as her evidently artsy ex-husband, is a well-heeled snobbishness and solipsism that extends, by action and implication, to Isabelle herself.

It is in this unshowy, unsparing examination of class and social status that Let the Sunshine In shows its hand. In 2013’s Bastards, Denis railed against late capitalist monsters whose deep pockets subsidised bottomlessly depraved appetites. Now, working in what seems to be a lighter mode, she continues her project. When Isabelle explains to a female friend that she was only able to come during sex with one well-monied lover by focusing on her disgust for everything he represented, it’s a startling, hilarious, lacerating moment.

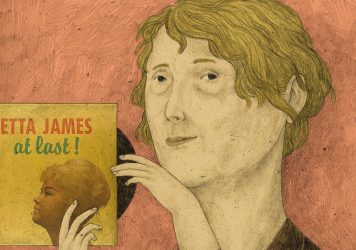

The word she repeats in her story, over and over, is “bastard”, explaining how naming him as such (to herself) is what allowed her to get off: it’s a put-down that’s also a confession. Conversely, after hooking up with a man from outside her circle – the first truly romantic figure in the film, heralded by an Etta James soundtrack cue – Isabelle is coerced into doubt by a colleague who acidly asks if her new partner is on “welfare”. Later, she parrots this same condescension at her lover, whose response is devastatingly sad.

Denis isn’t simply making a movie about the difficulties – both externally imposed and dredged up from within in response – for women on or past the threshold of middle age to find, reclaim, or fully disavow “true love”, which is itself a rich and original theme. She subjects her heroine (and, some might suggest, projected alter ego) to an analysis of how and why she makes her choices. In a lesser movie, it would simply be a case of grotesque men lined up unappetisingly in front of a woman who deserves better, even if we know it and she doesn’t.

Yet in writing, direction and acting (Binoche is as good here as she’s ever been), Let the Sunshine In is considerably more complex, and less flattering, both to its audience and the character. Isabelle’s plight is circumstantial and self-willed: the film’s funniest and most cathartically surprising moment takes place during a group walk in the woods and involves a leather-lunged rejection of her peers’ entitled largesse, which also contradicts her own professional aspirations. Where a Michael Haneke would be cruel (and probably cast Isabelle Huppert to play up the character’s self-destructive tendencies), Denis, who can also sometimes be stringent to the point of acidity, plays fair, and also funny.

On this point: after two viewings, I’m still not quite sure what to make of the film’s bizarre and quite hilarious extended coda. This finds Isabelle – stung by yet another break-up and seemingly at her wits’ end – soliciting the advice of a self-styled psychic (played, amazingly, in bull-necked close-up by Gérard Depardieu). Lulled by his patter and promises of better things to come, she absorbs dubious advice with what might be a flake’s naiveté or else the relief of somebody allowing herself at last to be guided down a different path. (“Be open,” he tells her, slyly echoing the radio broadcast in Denis’ Vendredi Soir that compels Valérie Lemercier’s character to o er a ride to a stranger en route to a one-night stand).

If it’s hard to reconcile the nervously smiling, deferential woman in the final sequence with the driven, con dent artist seen earlier, the shift fits Denis and co-writer Christine Angot’s daringly elastic approach to characterisation. And, taken from the right angle, it permits the possibility of a happy ending after all.

Published 18 Apr 2018

Claire Denis has raised the bar extremely high for herself.

Scintillating and complex, boasting a career-best performance from Juliette Binoche.

Much more than a stop-gap before Denis tackles her first sci-fi movie, High Life.

By Violet Lucca

French master Claire Denis gets seedy and sinister with an extraordinary modern riff on the classic noir thriller.

One of greatest directors working today picks apart the romantic gamesmanship of her wonderful latest.

The French actor gave an inspiring talk about gender equality at the Cannes Film Festival.