Pixar’s latest transoceanic odyssey is a pixel-perfect comedy about learning to overcome adversity and disability.

“Hi, I’m Dory. I suffer from short-term memory loss.” The words that open Finding Dory may sound like the introduction to an AA meeting, and may neatly recap the two most pertinent facts about the identity of the film’s heroine (voiced again by Ellen DeGeneres) – but the speaker is not the Dory that we know and love, but an adorably juvenile version of her, from before Finding Nemo, in what has now lately become a Pixar franchise.

Andrew Stanton and Angus MacLane’s sequel begins with a glimpse into the regal blue tang’s childhood, back when she had a mother and father (Diane Keaton, Eugene Levy) who fretted over the dangers of her congenital inability to retain memories. A momentary separation from them led Dory to forget who her parents were and where she lived, and to remember only herself (Dory) and her condition (short-term memory loss) – until, having grown up wandering the seas lost and alone, she ran into a neurotic clownfish named Marlin (Albert Brooks) and joined him on his quest to find his abducted son Nemo (Hayden Rolence).

If this introductory sequence of events – the prehistory to Finding Nemo – is now essentially forgotten by Dory, it is also completely new to us, so that when fragments of Dory’s memory return in a rush, sending her, with Marlin and Nemo in (under)tow, on a transoceanic odyssey to find her own family, we too share in her fuzzy nostalgia for a long-lost past. Indeed, older viewers may by now only half remember the escapades of the original film (released some 13 years ago), while younger ones may, like Dory herself, in effect be reconstructing this befuddled fish’s life story as if for the very first time.

As the ever perky Dory defies the odds to search for her parents outside, inside and all around the Marine Life Institute in Morro Bay, California, her adventures school younger members of the audience in the positive lesson that everyone has a unique set of qualities, and can get by with a little help from their friends. The recurring marine motif here is disability – not just anterograde amnesia, but Nemo’s conspicuously damaged fin, the near-sightedness of a whale shark named Destiny (Kaitlin Olson), the impaired echolocation of beluga whale Bailey (Ty Burrell), the cross-eyed confusion of common loon Becky (Torbin Xan Bullock), and the missing tentacle of Dory’s new best friend, the cantankerous red ‘septopus’, Hank (Ed O’Neill).

An expert in the art of camouflage and self-concealment, Hank wants nothing more than to be placed permanently in an aquarium, having once been hurt in the open ocean. His flexibility and timidity, coupled with Dory’s vulnerability and derring-do, make for a complex dialectic on the different ways in which the disabled can interact with the world beyond – while, more troublingly, two otherwise helpful sea lions (voiced by Idris Elba and Dominic West) are shown casually manipulating and bullying a third (also voiced by Bullock) with an evident intellectual disability.

Still, the overall message is that, no matter how small, hopeless and alone one might feel, anything is possible for those who work together. Even Dory proves able to travel across oceans, marine parks, bridges and even freeways in her quest to be reunited with her Blue Tang Clan. The results are beautifully animated, relentlessly paced, and often very funny – and if you are looking for guidance through these sink-or-swim times of historical amnesia, political befuddlement and goldfish-bowl isolationism, just keep asking yourself: “What would Dory do?”

Published 1 Jul 2016

Finding Nemo was pretty, but does it really need a sequel?

Pixel-perfect panoramas and enough gags to fill the seven seas.

In keeping with the times, it’s fast and loose with facts and probabilities, but has all the feels.

LWLies reports from the beguiling Bay Area basecamp of one of the world titans of feature animation.

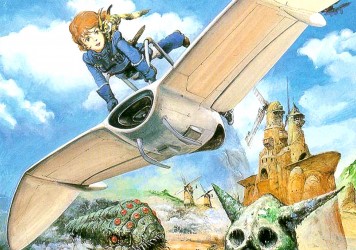

Gorgeous original artwork spanning three decades of the iconic animation studio.

Pixar are firing on all pistons with this wonderful, colour-coded exploration of a child’s inner psyche.