Tom Hardy goes for broke in this pedestrian twilight-years biopic of notorious mobster Al Capone.

A pallid, mouldering, altogether Orlokian version of Al Capone staggers across his palatial Floridian compound in little more than a bathrobe, both his adult diaper and solid gold tommy gun fully loaded. With a carrot clenched in his perma-snarl (all the cigars were exacerbating the syphilis that has melted his brain into a thin bisque), he opens fire on his scrambling, terrified groundskeepers. He does not know where he is or what’s going on; we don’t know if this is real or just another figment of his confused psyche.

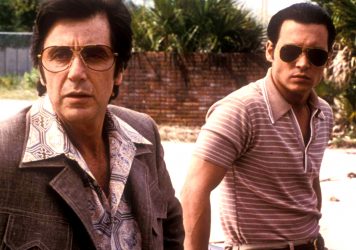

Everyone’s foggy on context, but the moment plays best without it. Brief snatches of hammy transcendence such as this have been swaddled in a film that cannot hope to keep up with them. The odd ends sticking out of Josh Trank’s biopic focused on the infamous gangster’s twilight years – the Louis Armstrong impersonator, the shartings both deliberate and less so, Tom Hardy’s go-for-broke performance in the lead role – leave everything else feeling pedestrian.

When Trank really reaches for the artistic brass ring the recent wave of career reappraisals have suggested may await him, he keels into a diverting strain of madness. For the most part, regrettably, he’s content to slap a golden filter over tired gangster geriatrics. If it’s not dazzling its audience with over-the-top madness, the film looks as wormed-over as the decomposing lump of man at its centre.

Hardy plays Capone as a macho Norma Desmond, an icon of fading grandeur transmogrified into a ghoul wandering around the remnants of his empire. This comparison illuminates a lot of the more out-there choices Hardy makes about his own physicality; the dinner-plate-eyed stare accentuated by his bloodshot blue contact lenses and the strangulated voice making him sound like he wants to get that dastardly Mickey Mouse owe more to silent film than the example of the actual Capone. Whatever his motivations, Hardy ensures that everyone can see all the work he’s put into this role, an effortful method trying too hard to make him as impressive as he’d like to appear.

“The gangster epic to which Trank owes the most is Gotti, from the overall off-brand aura to the distracting facial prosthetics.”

Hardy guides his Capone through the same late-in-life crisis most recently laid out in The Irishman, partially comprehending of all the damage wrought and partially unable to reckon with it. The 2019 gangster epic to which Trank owes the most, however, is the ignominious Gotti. From the overall off-brand aura (Trank visibly burned through most of his budget securing the sprawling Everglades estate location) to the distracting facial prosthetics to the listless stabs at drama, it all smacks of Kevin “E From Entourage” Connolly’s directorial non-signature.

That attempt to raise the dramatic stakes comes from a subplot about a $10 million cache Capone may or may not have stashed on his property, one of a half-dozen story wisps dissipating as the Fonz loses it. His wife (Linda Cardellini) won’t stand for his senility, his right-hand man (Matt Dillon) and feckless fail-son (Noel Fisher) have plans of their own, his oily doctor (Kyle MacLachlan) seems to play it fast and loose with the Hippocratic Oath, and the alligators lurking around his pond want to eat his testicles. This all sounds like it should make for a fascinating, flawed, messy, overstuffed movie, and yet in practice, it only sporadically breaks the ceiling on ‘interesting’.

Trank passes off a certain recklessness as ambition, his ideas indulged not as part of a bold creative scheme but as the expression of a desire to do whatever studios wouldn’t let him. But this isn’t the finger-to-the-system magnum opus that would’ve fit so tidily into the director’s career narrative; like the living mound of pulverised chuck steak carrying his film, Trank barely has control over what he’s doing.

Published 13 May 2020

Could it be that Josh Trank has simply been wronged by the biz?

It would appear that that is not the case.

We’ll always have the sharting.

Christine Blundell takes us inside her London academy.

Johnny Depp is on career-best form in Mike Newell’s classic crime-thriller from 1997.

By Luís Azevedo

Is the American mobster movie destined to go the same way as the western?