This saccharine religious comedy from Belgium’s Jaco Van Dormael fails to live up to its initial promise.

The various depressing global events which coloured the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016, added to the the unusual frequency with which beloved celebrities have been dying, could truly make anyone take the premise of The Brand New Testament very seriously indeed. Maybe the reason why this world often seems cruel is that God himself – supposing he exists – is a bitter and selfish man.

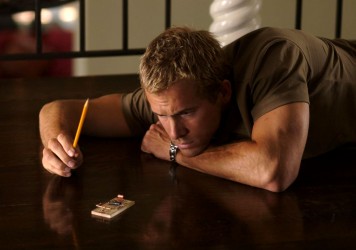

In Jaco Van Dormael’s film, God takes the shape of actor Benoît Poelvoorde, whose customary screams, eruptions of violence and brash dynamism are employed here to the full. For undisclosed reasons, God lives in Brussels with his shy and quiet wife and their daughter Ea (Pili Groyne), who begins to follow in the rebellious footsteps of her brother, JC (David Murgia). One day, tired of His inhumanity, she finally decides to enter her dad’s private room. Using the computer with which He controls the world, Ea decides to reveal to every human being their date of death via text message. If one can accept the very ordinary world so far established, the effects of Ea’s action mark the beginning of the film’s downward spiral into the irritating and the incoherent.

Ea’s intention when sending these fateful texts only becomes clear when her brother JC states it himself and his predictions are confirmed. Knowing the exact moment of their death, people lose faith in God and decide to act according only to their desires. However, one could imagine another version of the script where, knowing how short a time they have before Judgment Day, people would become extremely devout and thus empower this God, however severe He may have been. It is naturally pointless to criticise a film based on what it does not do rather than on what it does, but the chain of events triggered by Ea never quite convinces and thus proceeds on shaky foundations.

The Brand New Testament relies on that typically Belgian hybrid of tones, where bleakness and violence are contrasted with syrupy sentimentalism. The latter progressively dominates the film, and with mixed results, as Ea goes in search of the six mortals she has chosen to add to the existing 12 apostles. These characters come from drastically different walks of life and each story of rediscovery in the face of death is presented as a new gospel. Their meanings, however, are not as distinct as the protagonists themselves. The progressive intersection of their stories could have been constructive and powerful had Van Dormael not chosen to promote a defensible yet simplifying and muddled romanticism. His good intentions limit his scope to the Power of Love instead of widening it to the entire spectrum of the human experience.

The epilogue further undermines the persuasiveness and credibility of the director’s good heart. Suddenly, touches of utopian and fantastic feminism, environmentalism (more precisely, tolerated inter-species romance) and rightful drastic punishment appear as last minute flourishes rather than central concerns. Humanity will have to wait if it wants another, more credible Testament.

Published 14 Apr 2016

Belgian comedy is often hit-or-miss, sometimes worth to risk two hours of your time.

Time passes slowly and fades away and ‘love’ definitely isn’t ‘loving’.

Do not waste the unknown number of hours of life you have left on incoherent schmaltz.

By David Hayles

With The Brand New Testament out this week, here are six other memorable depictions of the Almighty.

If you only do one thing this year, make sure you catch this shattering masterpiece by the Dardenne brothers.