Michelle Williams and Mark Wahlberg battle the might of an unfeeling empire in Ridley Scott’s latest.

Funny old thing, money. The idea of that a surplus of wealth can be as detrimental to a person’s wellbeing as a deficit has long fascinated novelists, playwrights and filmmakers alike, who all seem to draw the same conclusion: you can’t put a price on happiness. Of course, to be poor is to know that having money certainly makes misery easier to stand.

All too often creative folk in a position to preach seem keen to convince us that the One per cent are, at their core, the same as the 99 per cent. John Paul Getty wasn’t the One per cent. He was the 0.01 per cent – not only the richest man in the world, but the richest man ever. At the very least, Ridley Scott seems to understand the unique position this affords his characters in All the Money in the World. Right at the start of the film, Charlie Plummer’s unfortunate John Paul Getty III states as much: “We look like you, but we’re not like you. It’s like we’re from another planet where the force of gravity is so strong it bends the light. It bends people too.”

Based on true events, Scott’s historical drama-cum-thriller depicts the kidnapping of oil magnate Paul Getty’s 16-year-old grandson in 1973, and the subsequent five-month negotiation with his captors to secure his release. There’s a heavy dose of dramatisation and fictionalisation given to proceedings – so much so the film mentions it on two separate title cards – perhaps in order to avoid the ire of the considerable Getty dynasty (who are worth about $5.4 billion nowadays), but this doesn’t necessarily detract from the truly fascinating subject matter. Nor does it mean that Michelle Williams and Christopher Plummer pull punches in their performances as JP Getty and his estranged daughter-in-law Abigail.

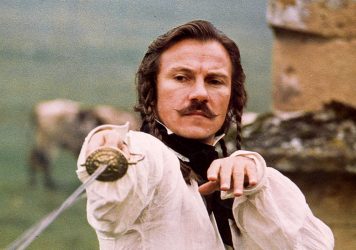

It’s impossible to detach Plummer’s role from the circumstances under which his last-minute casting came about, but the actor’s considerable talent shines through regardless. His JP Getty has something of Ebenezer Scrooge about him, but for the most part avoids straying into overwrought Scrooge McDuck parody thanks to Plummer’s natural charisma. He gives us an unpleasant, single-minded miser, but one we can believe in. The majority of us will never be able to comprehend what kind of person spends five months negotiating the life of their own flesh and blood when they have the means of guaranteeing their safety in a matter of minutes. Getty gambles his grandson’s life on principle, and when asked what the richest man in the world could possibly want, tells only the devastating, ugly truth: “More”.

Michelle Williams is the perfect foil to him as JP Getty III’s mother, vulnerable and stoic at once, unflinching in the face of Getty Sr’s constant undermining. There are similarities between Abigail and her father-in-law, and the film would do better to afford Plummer and Williams more time to explore these. Unfortunately, Scott’s framing of the film is slightly off – rather than focusing on the Shakespearian power play between warring factions of a dynasty, he instead brings us… Mark Wahlberg.

Cast as Getty’s ex-CIA lacky Fletcher Chase who’s tasked with negotiating with the kidnappers, Wahlberg valiantly attempts to play it straight, but the framing of his character as heroic is unconvincing and boring, threatening to turn the film into an overwrought thriller in the vein of Taken, albeit lacking Liam Neeson’s earnest charm. The story is compelling enough without including a figure like Chase, and ultimately would be more interesting without him – a kidnapping treated like a business deal rather than a hostage negotiation is a far more interesting concept than Scott actually delivers.

Similarly, Scott muddles through the actual reason for the kidnapping, flirting with conspiracies and Communism, and there’s a considerable number of details which are omitted or brought up and then never resolved in a satisfactory manner. Towards the end, the film strays into outright melodrama, and misses the opportunity to reflect, even briefly, on how the kidnapping impacted on the victim himself.

It’s a shame, because there’s much to love about the film, from its muted colour palette as cold as hard cash to Daniel Pemberton’s score (with shades of Handel’s sublime Sarabande) but Scott, as seems to often be the case, remains hung up in the idea that there always needs to be a hero in his story – but when the central character is greed manifest, pretending otherwise is a woeful oversight.

Published 4 Jan 2018

If nothing else, it’ll be fun to see how those reshoots blend in.

Plummer and Williams are astounding.

Flashes of greatness, dampened by a hero complex.

By James Clarke

The director’s 1977 feature debut contains several key thematic and stylistic hallmarks.