Laura Poitras' portrait of activist and artist Nan Goldin is a damning indictment of the US pharmaceutical industry and a touching look at a familial tragedy.

Nan Goldin leaves no moment uncaptured. Hers is a world as intense as it is varied, as possessive as it is forgiving. It unravels and gains its texture in dimly-lit homes and nightclubs, on messy motel beds, in spaces shaped by and for the people who exist in them. People enveloped in the haze of sex and drugs, of intimate and violent encounters, of relationships that give life and those that take it. Her seminal contributions to the world of art and activism make for the perfect documentary subject for a filmmaker of Laura Poitras’ calibre.

“I survived the opioid crisis. I narrowly escaped.” Goldin narrates from her heartbreaking essay published in Artforum magazine in 2018, before going on to reveal an ongoing and tireless fight to expose the hubris that unleashed suffering of biblical proportions. Many of the lives claimed by the opioid crisis had their start with the prescription painkiller OxyContin. This lethal opioid was manufactured and ruthlessly marketed as a “miracle drug” by Purdue Pharma, a company owned by the billionaire Sackler family known for their lavish donations to the arts. Their family name has long stained the walls of countless institutions – from MoMA, the Met and The Guggenheim, to the Louvre, the Tate Modern, and the National Portrait Gallery – their vast fortune amassed by means of washing their “blood money” clean through the public façade of cultural philanthropy.

Goldin’s own experience with addiction led her to spearhead the fight against systemic injustice, forming the advocacy group Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN). Not only to shame the filthy rich bastards whose grotesque, mercenary greed played a huge part in manufacturing the opioid crisis; not only to draw attention to the art world’s complicity; but to tangibly address the effects of the crisis by tackling harm reduction and the stigma surrounding addiction.

Part life-spanning artist portrait and part chronicle of Goldin’s efforts to bring down the Sacklers, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed excavates the deeply-rooted trauma and life force behind Goldin’s work. Her activism stems not just from her history with addiction to OxyContin, but a life coloured by mental illness, drug abuse and the deaths of friends and family. Her vast body of work is inexorably rooted in the deep scar tissue made permanent by the sharp daggers of loss. In allowing these interconnected sections to converge, Poitras lends a deeply propulsive energy to the connections and political throughlines that are so dexterously drawn between them.

The film details Goldin’s upbringing against the backdrop of 1960s suburbia – that hellscape bound by repression, convention and homogeneity. When Goldin was only 11, her 18-year-old sister Barbara (to whom the film is dedicated) saw that suicide was the only way to battle the repression of her sexuality. “All the beauty and the bloodshed” is a quote directly pulled from a mental health evaluation written by a psychiatrist at one of the institutions Barbara was sent to before taking her life. Other significant losses came through the AIDS epidemic which scythed through the queer subcultures of NYC and beyond.

It was during these years that Goldin established herself as one of the most exceptional artists of her generation. Those were the years filled with violence, censorship and grief, the loss of Lower East Side starlet Cookie Mueller and close friend and collaborator David Wojnarowicz, the profound loss of innocence through violence as embodied in the full-frontal view of Goldin’s mop of curls surrounding her bruised face after being beaten by an abusive ex. These aspects of Goldin’s life are one and the same – her early work, her proximity to the AIDS epidemic and the ACT UP protests that led to her activism work with PAIN, prompt a thorough understanding of what it means when activism works in tandem with art.

As with her sister before her, Goldin would move from one foster family to another, and in growing accustomed to the feeling of alienation, became eternally infatuated with life on the fringes. In losing the memory and tangible sense of her sister, Goldin vowed never to lose the real memory of anyone again – a desire that is a subject in itself within her photographs: to hold onto, preserve and restore a tactile sense of bearing witness by committing images to eternity. It makes sense, then, that she would choose to collaborate with Laura Poitras, a filmmaker with a bone-deep understanding of the urgency of bearing witness.

“This is not a bleak world,” Goldin writes in her prescient preface to ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’, the photographic landmark that distilled the essence of ’80s downtown life, “But one in which there is an awareness of pain, a quality of introspection.” Like all ballads, its vernacular is simple and concrete, its sequencing measured and meticulous. Louche lovers, friends and strangers sprawled in bathtubs, lying supine on sofas and across the backs of convertibles – people bonded not by blood, but by a similar morality, the need to live fully and for the moment – seen in candid light, captured in and out of bed in pre- and post-coital moments, posing, celebrating, immortalised with feral immediacy. The rich mélange of experience as depicted through her trademark slideshows has the power to resist, rupture and make noise, to move against the tide of “good taste”.

Treading new emotional ground with artful measure in her pivot to artist portraiture, Poitras soaks the film in the sensuality, candour and affection of Goldin’s photography by punctuating the seven interconnected chapters (each relating to a different portion of Goldin’s life) with her collaborators’ slideshows flickering to their eclectic soundtracks of opera, ’60s pop and ’70s rock. The effect is nothing short of beguiling. Sharp, intrepid and compassionate in her direction, Poitras casts the viewer under a hypnotic spell that’s equally charged by Goldin’s recollections on the personal tragedies that have helped to motivate her fight against the Sacklers.

This is Goldin’s film as much as it is Poitras’. In the same way artifice would corrupt a Nan Goldin photograph, gloss and glamorisation don’t belong in a Laura Poitras documentary – her work seldom succumbs to bleakness for dramatic effect. Bold structural ambition undercuts the visceral, complex struggle between autonomy and dependence that’s baked into the core of Goldin’s work, with the sheer range of media and versatile discussion channelling the bottomless wells of rage and pain into a war against Goliath.

The pantheon of art-led protest has gained a formidable ringleader in Nan Goldin, who brings striking aesthetic direction to PAIN’s deftly-staged actions. Hundreds of orange prescription bottles labelled ‘Prescribed to you by the Sackler family’ are launched into galleries and several mass ‘die-in’s’ are staged on museum grounds. Goldin’s vast history with addiction and loss allow her to tackle this conflict with a strongly personal, life-spanning perspective, to ensure that at least one domain over which the Sacklers sought influence is forced to reckon with funding culture through tainted funds. Victories are small yet tangible, and come in the form of rejected donations by arts institutions and the removal of the Sackler name from the walls of many wings and galleries.

As an artefact of the invaluable intersection between artistic effort and pragmatic resistance, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is a testament to the dialectic of form and content, of artwork and social reality as a crucial, actively-engaged site of political struggle, an apt battleground in the fight against all-pervasive capitalist monoliths.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 24 Jan 2023

Laura Poitras strays from her usual subject matter and wins the Golden Lion.

This is essential viewing – an unequivocal use of the documentary form as a means of urgent protest.

Stellar. Rambunctious. Profound. Life-affirming.

Laura Poitras’ real-life spy thriller shows how and why Edward Snowden stepped up to blow the whistle on government spying.

Filmmaker Kirsten Johnson repeatedly offs her father in this darkly funny and profound meditation on life and loss.

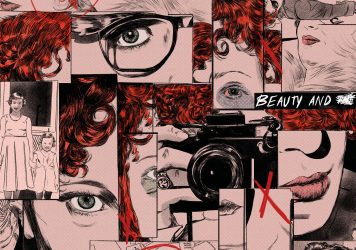

Discover our punk zine homage to Laura Poitras’ extraordinary non-fiction portrait of photographer Nan Goldin.