Two men, operating as a single creative body. Little White Lies was offered a rare audience with the Coen brothers.

Nards to the Oscars. Remember: Inside Llewyn Davis is still an incredible film, with or without some revolting commercial hat-tip. The Coen brothers are still two of the greatest living filmmakers, their back catalogue an embarrassment of tragi-comic riches. Their latest movie sees Oscar Isaac as a cantankerous troubadour wandering the sleet-lined streets of early ’60s New York in search of commercial acceptance. In this interview, LWLies discussed the brothers writing process, the meaning of ‘making it’, whether they channel their own personalities into their characters and their thoughts on The Godfather III.

LWLies: [Points to rain and drizzle outside window] It’s nice weather for the film.

Joel: Yeah, perfect. We’ve been sayin’ that all day.

Ethan: Appropriate for the movie, and it’s weather you expect when you come to London.

Joel: Are you from London?

Yeah, yeah. North London. It’s always like this.

Ethan: There’s a Flann O’Brien novel… which one is it?.. they talk about, ‘a legend has been passed on down the generations and once in the distance, this warm orange thing appeared in the sky. People still talk about it’.

This movie was inspired by the Dave Van Ronk book, ‘The Mayor of MacDougal Street’. When you read these things, are you always looking for movies in them?

Ethan: Not at all. You lead your life, you do what you do… Just no. Some people do that.

Joel: Yeah, some people do. They cruise for it.

Ethan: They keep a journal. We’re not journal keepers.

Joel: No, we just read and listen and do whatever we do and then every now and then, something happens. It’s that old ‘ding, ding, ding, ding!’ thing. And it’s rare that you find an entire film, it’s more an interesting part or facet of a story. That’s all.

Has that ‘ding, ding, ding, ding!’ thing become more of a regular occurrence as your careers have progressed and you’ve made more movies?

Joel: I don’t think you hear it often at all. Every now and then it happens, pretty much at the same interval. I remember when we were doing Barton Fink, we both read this book. It was a non fiction book, a history of Hollywood in the ’40s that was from a very interesting and specific point of view.

Ethan: It was mainly about German expats in Hollywood, and it was called ‘City of Nets’ by Otto Freidrich.

Joel: For some reason, that one set the alarms off. We agreed that there were things – details – about this period which were interesting and would’ve maybe made an interesting setting for a story. And I think that’s how ‘The Mayor of MacDougal Street’ fits into this. It’s a little bit different as we’d had this idea in the back of our heads about making a movie set at that point and concerning the life of a folk singer for some time. And then later we read Van Ronk’s book. That catalysed it for us.

We understand you don’t write a plot outline before you attack a script. Did Llewyn Davis ever go in any strange directions when you were piecing the story together?

Ethan: Not really. In spite of the fact that we don’t outline and don’t generally know what’s going to happen later in the story when we’re still early on in the story, in the case of this one, we recognised early on that we wanted to have the beginning come back and be the end. Even before we had any idea of what was going to happen in the middle. Then… it goes where it goes… It just goes where it goes. We don’t worry about it. We don’t even worry that it might not come together at the end.

Joel: Which sometimes happens! There are little things that you chase up and down which eventually don’t end up in the script. We tend to feel our way through a film.

Even something that feels like its been intricately plotted, such as Miller’s Crossing?

Ethan: It is something we wrote in that way, and actually I think that’s how most people who write those kind of things work. Raymond Chandler would just try and figure it out as he went along. He would make insanely complicated situations for himself and then work his way out of them. I think that’s not too unusual.

Joel: Charting it all out ahead of time is, in a way, harder. Sometimes you’ve got to just peg yourself in a corner and then think, ‘well this is what it is, now how the hell do I get out of it?’

Is this how screenwriting is generally approached?

Ethan: Is this how it’s done?!

Joel: Would this method be recommended?! Probably not.

Robert McKee would be weeping if he saw you work.

Joel: Exactly.

Ethan: It’s funny because we talk about that. We talk about how we should ask Robert McKee for advice.

Joel: Sometimes we get stuck…

Ethan: … and we just want to call him up and ask, ‘Mr Mckee, are we doing it wrong?’ No, but when we write a movie, we don’t worry about doing it wrong. People following that templated route, they do an outline and they make index cards. I’ve read that. They put index cards up on the wall.

Joel: We’ve read about people doing that. I even think Coppola does that. He made lots of index cards when he was working on The Godfather III.

Ethan: Well there’s the argument against index cards!

Joel: That’s true. I wonder what he did on [Godfather] II though? That was pretty good… He was probably telling everyone, ‘but I used them on Part II!’

Would you ever consider trying the McKee/index cards method of writing? For fun.

Joel: Maybe just as an experiment.

Ethan: See what happens.

Joel: It’d probably take us forever. We’d be sat there years later, filling out index cards.

Ethan: Where does this one go again?

Joel: Or, you finish the screenplay and find a card that slipped under the table! Oh fuck, I was supposed to put this in! The DVD making-of would be great.

Ethan: Just us making index cards. For seven hours.

Did you decide to make Llewyn an asshole early on in the process?

Joel: Yes. I don’t know whether we talked about him in the sense of an asshole per se, but early on, it was clear to us we were talking about a character who wasn’t entirely sympathetic. We wanted him to be sympathetic, but we wanted there to be things about him that were difficult. We wanted to make it clear that he was also difficult to himself, that in certain ways he was his own worst enemy.

Ethan: There’s a way to relate it to what you were saying, the whole thing. We started with the idea of a folk singer getting beaten up round the back of Gerde’s Folk City, or whatever. And it was clear to us that we didn’t know who was beating him up or why, but we kind of sensed that…

Joel: …he wasn’t entirely blameless.

Ethan: It was not mistaken identity or anything like that. He had fucked up somehow.

People don’t get beaten up for being nice.

Joel: Exactly.

Ethan: The extent to which is brings it on himself is an interesting question, but one that you want to raise.

Joel: In that respect, we were thinking about him in that way.

The film is ambiguous as to whether he makes it as an artist or not. Do you think his character is what leads him to not being a success within the timeline of the film?

Ethan: Again, that’s the question you wanna raise, and not definitively answer.

Joel: You must recognise the fact that those equations are always complicated. Questions that weigh on that and could contribute to it, and make them palpable in the story.

Ethan: I think we also have to question what constitutes ‘making it’. Clearly, unambiguously, he’s not going to make it on the terms that the other character we see at the end of the movie does make it. Why is that beyond his formulation of the idea of making it?

Troy Nelson makes it. Do nice guys make it?

Ethan: Oh no! Who believes that? Sometime raging assholes make it. It’s just another way to rub salt in Llewyn’s ass, as it were. That this nice guy seems to be more successful than he, Llewyn, is.

Joel: There’s also another aspect to the whole thing which is interesting. It goes back to the nature of folk music, it goes back to those questions you were asking about the nature of success. You’re right, Troy is the nice guy in the movie, but Llewyn also talks about him about him as being a little bit insipid. But there’s also something sweet. The song itself is a beautiful song, but has that sweet and bordering-on-the-insipid aspect to it too. It contains all of those things. You can see why the artist would be successful. It’s not entirely one thing or the other. It’s also interesting that Llewyn would have a somewhat ambivalent relationship to his own art and his own place within the music industry. They are all things that are part of the same question.

Do you think Llewyn is a representation of yourselves as artists? Do you think you are misunderstood?

Ethan: No, not really.

Do you ever project yourselves into your characters?

Ethan: Not consciously. We make the stuff up so obviously to some degree you invest something of yourself in it. But it’s not what we’re thinking about. We’d be the last people to ask about that. In terms of how we operate, our characters find everything difficult. Everything’s difficult. It’s all difficult. We don’t find that. We just don’t. We find that we haven’t had to contend with the world conspiring against us to the extent that it seems to conspire against someone like Llewyn. We don’t relate to that.

Joel: But y’know, here’s the tricky thing: in a certain way, we have experience and practice in a certain thing, and that thing is making movies. The character is also making something. He has to deal with all of those same questions that anyone in that business, that artform of whatever you want to call it, has to deal with. In that respect, we’re sympathetic to, or at least we feel we have some direct relationship to the experiences that he has. Right, it’s the old cliché that you can only write about the stuff you know about. You also want to tell stories that people who don’t have any experience of that can relate to. Success, whether it’s an artistic thing, is something everyone thinks about and knows about. There are people who are good at what they do who are not successful, and that’s what the film is kind of about. You don’t have to be hip to the particulars of the business.

Published 1 Jan 2014

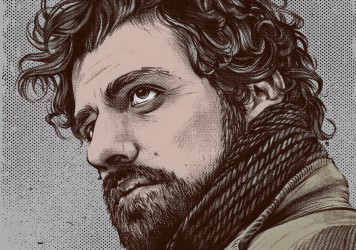

The Inside Llewyn Davis star chats to LWLies about getting into character for the Coen brothers’ latest.