Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle makes for a uniquely strange and self-indulgent viewing experience.

Described with fitting grandiloquence by the Guggenheim’s curator Nancy Spector as a “self-enclosed aesthetic system”, Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster Cycle is a series of five feature films of varying lengths that look, in various abstract and aloof ways, into human form and creation.

Created between 1994 and 2002, The Cremaster Cycle sits precariously in an uneasy space between visual art and cinema, seven hours long, with scope, production values and access that would make practitioners from either world jealous. A singular product of a period of popular engagement and public investment in contemporary visual art, Barney’s expansive, high-budgeted work is overflowing with characters, costumes, sculptures, and stuffed with allusion, symbolism and ideas. For better and for worse, there hasn’t been much like it since, and there perhaps won’t ever be again.

Taking the “male cremaster muscle, which controls testicular contractions in response to external stimuli” as its starting point, The Cremaster Cycle explores human (and non-human) biology in all of it’s grotesque and fascinating complexity. Consisting of a series of imaginative and digressive stand-alone sequences – a succession of phallic, vaginal, fallopian, and other indeterminately anatomical imagery – once combined the film supposedly charts the pre-developmental determination of gender across five stages of differentiation.

While that description sounds peculiar, the reality is even more so. A good way to give a sense of the film’s style – hard to pin down but unified by a recalcitrant, rebellious weirdness, its corporeal, queasy physicality, and a psychedelic, symbolic density – may be simply to describe some of the film’s occurrences as they appear in narrative order.

For the first cycle, the most gentle, straightforward and traditionally feminine, Barney shows chorus dancers pirouetting on a sports field, while above them inside two airships several troupes of uniformed attendants and a grape brandishing princess engage in mute dialogues, until the princess descends to join the dance.

In the second part, an oracle figure induces a sexual ceremony that culminates with an engorged, honeycombed penis ejaculating a live bee while Slayer’s Dave Lombardo plays drums in a recording studio full of humming bees. From here, bull riders practise their art in a remote salt-flat rodeo, a meeting takes place between two men in an isolated gas station that sees them exchanging flowing fluids through a piping system that connects their two cars, and Norman Mailer (playing Harry Houdini) tours a flooded, desolate warehouse.

In the third cycle, which is the longest, most elaborate and most interesting by some margin, Barney himself, dressed in a vivacious pink wig, tartan kilt, body paint and prosthetics, scales the levels of the Guggenheim’s museum floors, climbing the inner walls of the gallery. On ascensions, he faces a number of foes (amongst them duelling punk bands Agnostic Front and Murphy’s Law, an anthropomorphic leopard woman played by Paralympian Aimee Mullins, and the artist Richard Serra, who is creating a work out of amorphous gloop) in abstract battle.

Meanwhile, inside the Chrysler Building, classic cars battle each other in a carpark destruction derby, a meticulous barman sees his methods collapse into slapstick abandon, a leather clad woman chops potatoes with her razor heels, and a man, strapped into a dental chair undergoes a procedure that ends with a nebulous protrusion from his anus releasing several human teeth.

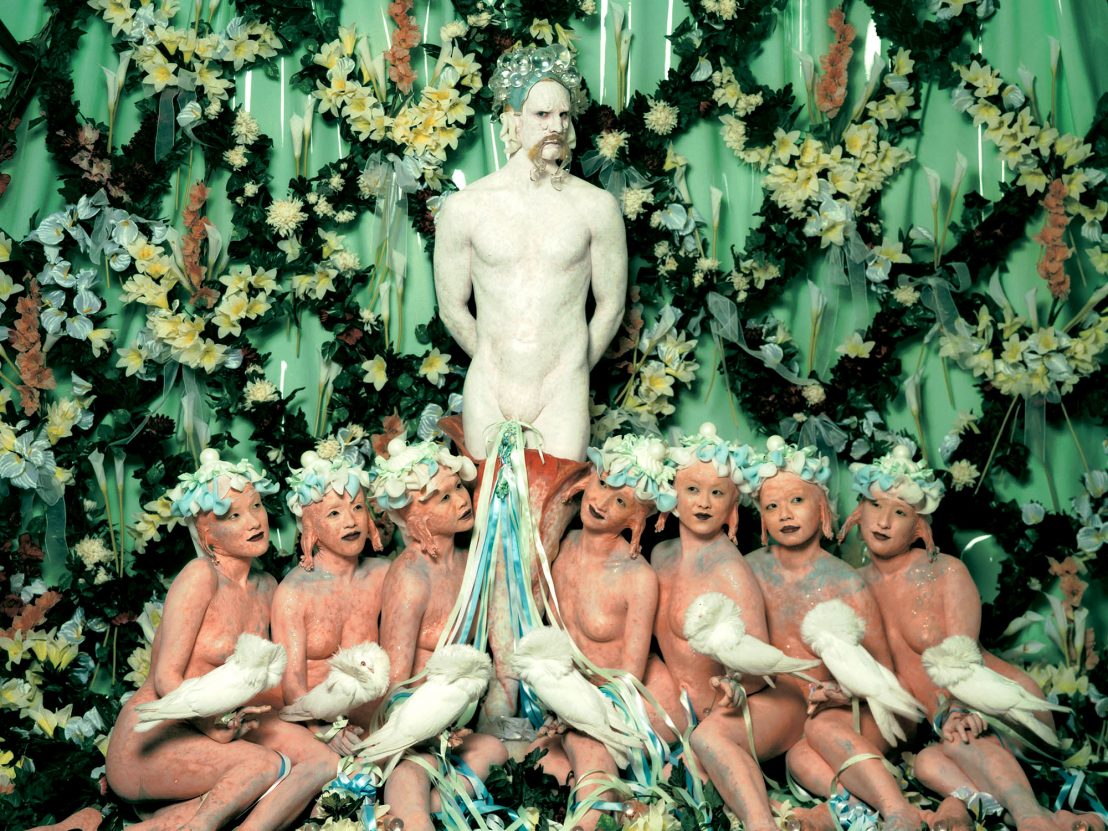

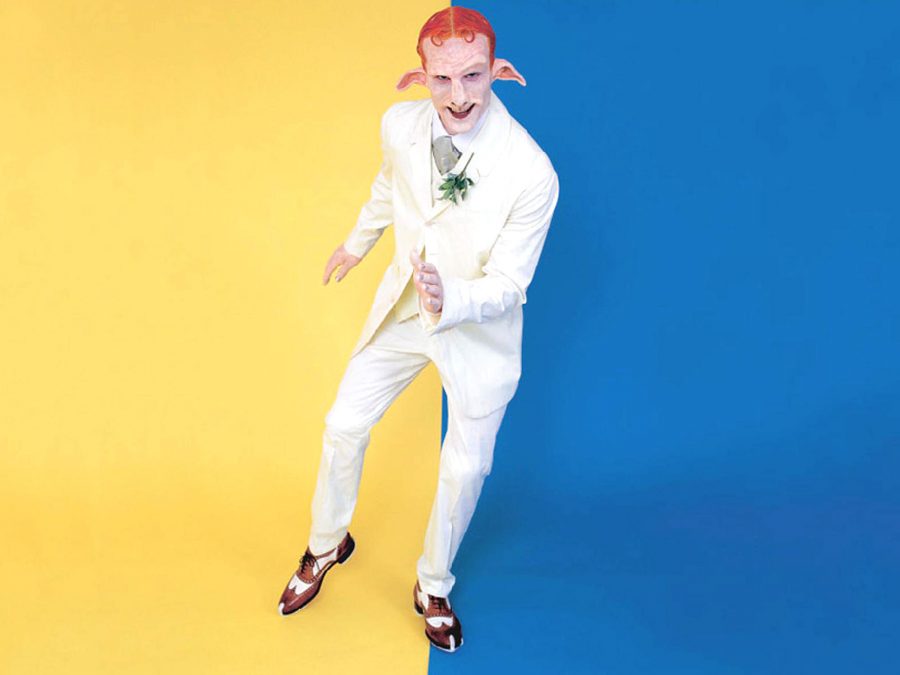

The fourth part sees yellow and red costumed motorcycle sidecar riders race around the Isle of Man while a red haired, pale skinned satyr figure tap-dances his way into the sea only to surface again crawling through a gelatinous, waxy cavity. For the fifth, it’s off to Budapest with a procession that sees underwater nymphs devote themselves to a merman whose penis is elevated by a flock of white pigeons. In both, Barney the auto-sculptor plays the plastically disguised leads, lending physicality to proceedings through his exaggerated mobility.

Absorbed all together, The Cremaster Cycle is an exhausting experience, demonstrating a weirdness that is wearying, a dedication to provocation that comes to feel laborious, and much material that feels like baggage. Yet, it is difficult not to be impressed somewhere by the inventiveness on display or the strength of its presentation. There is much to appreciate in the technical rigour shown in the visualising of Barney’s many ideas: the complexity of the staging and prop work; the flair of the costuming; the use of vivid colour and lavish decoration; elaborate prosthetic assemblages; the controlled, mobile camera; and Jonathan Bepler’s bombastic, invigorating score.

The film falls short in the assemblage of it all, edited without much rhythm and lacking any urgency or graspable through-line. Some will find pleasure in decoding the labyrinthian symbolism or identifying the many reference points, others will tire of dot-connecting when it’s laid out so abstrusely. What seems most missing – even disregarding debate over the meaning or merit of the many mini narratives that spiral outwards, are abandoned, or left to wilt in ambiguity – is an emotional component.

Since 2002, response to the work has stretched from the adulatory, labelling it as one of the major artworks of the cinematic form, to the contemptuous, who have found it to be empty and indulgent. Despite finding a home at a number of major art spaces upon completion, where it was presented alongside drawings, sculptures and props from the films, The Cremaster Cycle isn’t available on home video and is only screened periodically, under strict presentation conditions from the artist.

Birmingham’s eclectic Flatpack Film Festival screened Barney’s work in its entirety, showing the five films in numbered (non-chronological) order to a small, committed band of viewers from 11am to 9.15pm, with “regular breaks for decoding, head-scratching and sandwich consumption.” Much of all three took place, but little to no consensus was made over what had been seen, or even its value. Those that stayed to the end seemed worn down, weakened, and not necessarily convinced, but still fascinated by Barney’s strange, deeply self-indulgent act of creation.

Published 30 Apr 2017

Steve “Flying Lotus” Ellison delivers a sick suite of gag-inducing shorts at the 2017 Glasgow Film Festival.

A pilgrimage to the sleepy American setting of David Lynch and Mark Frost’s iconic show.

By Tom Graham

Twenty five years on David Cronenberg’s adaptation of William Burroughs’ classic novel remains a bold and transgressive vision.