Saul Williams and Anisia Uzeyman ponder post-colonisation in this percussive, transcendental Afrofuturist musical.

In the mesmerising, tech-saturated Burundi conjured by co-directors/life partners Saul Williams and Anisia Uzeyman for their unclassifiable, often mystifying film Neptune Frost, setting can safely take precedence over plot. The particulars of what’s going on in a knotty story involving actors sharing roles, conversant in a poetic dialect that filters character and motivation through hard-to-parse abstraction, may pose an obstacle to first-time viewers. “Unanimous goldmine,” for starters, serves as a salutation between the “resource-rich”.

But the sheer wealth of inspiration on display, along with the more legible themes of globalism’s growing pains, prove more than enough to compel a second viewing. Williams and Uzeyman work in a mode of rich ideas and vibes, both so plentiful that the narrative obliqueness feels less alienating and more like an inviting challenge. It earns the attention it demands.

In broad strokes, the script could be said to focus on the intimate, forbidden bond between on-the-lam intersex hacker Neptune (played first by Elvis Ngabo, then Cheryl Isheja) and rebellious miner Matalusa (Kaya Free). There’s a slow-burning love between them, but like the other emotional currents at play elsewhere, it’s attuned to a complex localised mythology befitting the project’s origin as a graphic novel.

A cataclysmic conflict between hazily defined factions is a-brewing, though the stakes – nothing short of the soul of Africa, denuded of its resources and left by industrial concerns to wither – are evident. The loose logic threading together the disjointed scenes does come in handy when the handful of electro-pop musical numbers set in, our gameness for whatever oddity the film can dish out extending to its spontaneous eruptions into song.

Among the more memorable soundtrack cuts is ‘Fuck Mr Google’, a scene that lays bare its oppositional stance to the encroaching exploitation by digital conglomerates. Matalusa labours in a coltan concern, a mineral used in the manufacturing of circuitry for cell phones and computers, and the toll they exact informs both the political alignment as well as the overall aesthetic with which it coalesces.

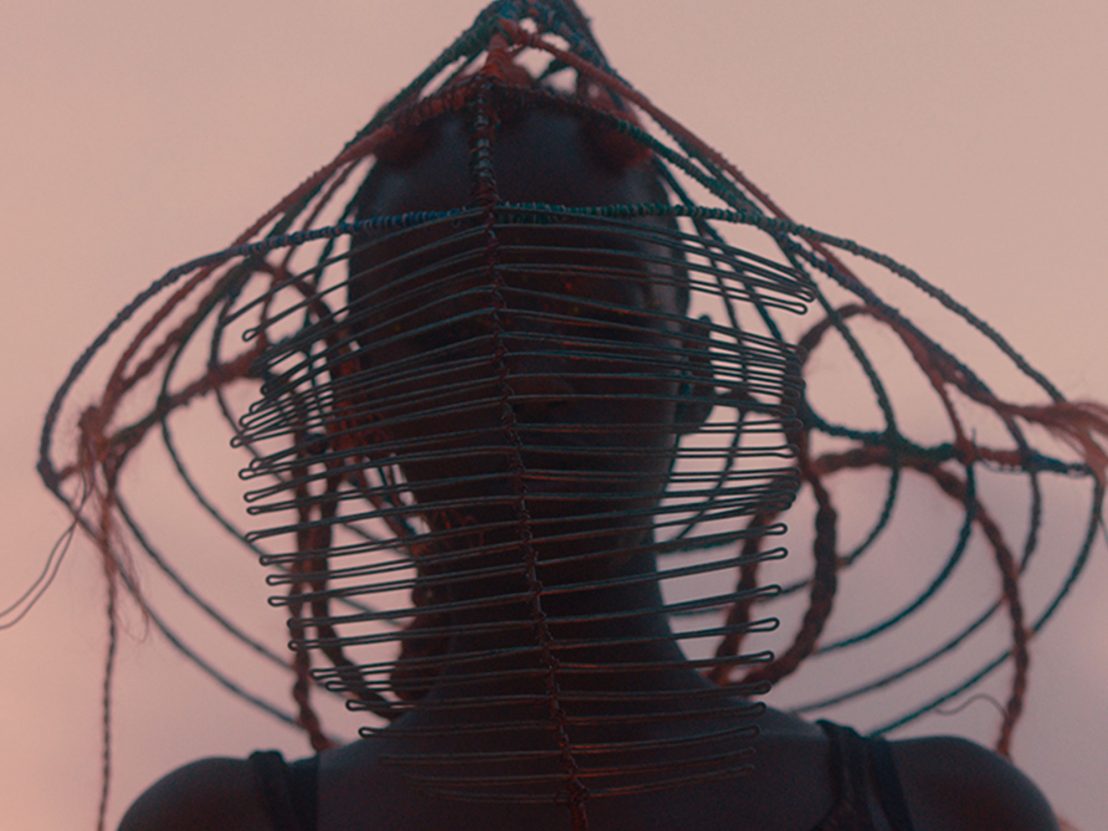

Embellished by blacklit pops of purple and orange, occasionally filtered through an effect simulating a TV set’s screen, their world imagines the dystopia of Mad Max as a more specifically cyberpunk wasteland. (The Afrofuturist cult classic Welcome II the Terrordome might be a closer point of comparison.) Everyone’s surrounded by the ruins of gadget capitalism, with some integrating the detritus into their fantastic costuming, metal face masks made of spare wiring and a coat studded with keyboard caps being two of the most striking examples.

The craftiness with which the characters repurpose these materials places them in line with a long, accomplished tradition of African art defined by deprivation and innovation. Whether cooking whatever would grow in an arid climate or making music with anything on hand (many of the songs employ this legacy of natural percussion and call-and-response repetition), the pattern of this history advances from making do into excelling, the same triumphant stand made with the cleverly recycled production design.

Williams and Uzeyman’s call to action sounds out with force and clarity, however tangled the path to it may have been. Though imperial entities will do their worst in the campaign to choke every last dollar out of the denizens in the region, the “motherboard” connecting all the characters through a virtual channel of spirituality, they won’t be cowed. The gizmos grow obsolete, but the people subjugated by their creation will endure forever.

Published 12 Sep 2021

A middle-aged man tends to a young girl with ice dentures in Lucile Hadžihalilović’s elliptical English-language debut.

The multi-hyphenate has created a hypnotic, incisive score for Charles Officer’s socially-conscious crime-noir.

By Erin Brady

Rob Savage’s follow-up to Host is a terrifying yet frustrating experience about social media narcissism.