Miguel Gomes dazzles and infuriates (but mostly dazzles) with a rambling love poem to his poverty-stricken country.

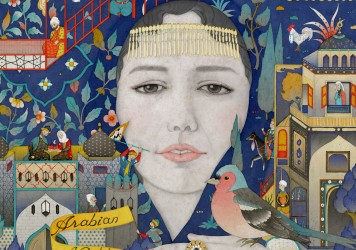

We’ve held off writing about Miguel Gomes sprawling, year-in-the-making tri-part doohicky, Arabian Nights, in order to see it in its entirety. “Like Star Wars, this is three films,” said the director at a Q&A session following a screening of the first volume. As such, the programers at the Directors’ Fortnight strand of the Cannes Film Festival decided to play it in three separate slots over six days.

Each visit, we would receive our fill of tall tales and then be given time to ponder their meaning, Gomes clearly hoping to divert us from our sub-conscious inclinations towards metaphorically beheading our virgin brides. The director takes one of literary history’s most spellbinding raconteurs as his muse and spirit guide – Scheherazade – and goes on to form a poetic diagnosis on the floundering, albeit naturally captivating cadaver of austerity-scarred Portugal.

This is not a literal adaptation of ‘The Arabian Nights’, it merely adopts its structure, its disposition, and – eventually – its sublime perspicacity. It comes across as a cross-processing of Buñuel’s Phantom of Paradise, Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St Matthew and the films of inspirational Portuguese filmmakers, Antonio Reis and Margaret Cordeiro. But even that doesn’t quite cover it.

As with his previous features, Our Beloved Month of August, Tabu and the short work, Restoration, Arabian Nights takes no heed of the supposed partition wall which divides the worlds of documentary and fiction, and throughout its three freewheeling chapters (The Restless One, The Desolate One and The Enchanted One), Gomes is clearly looking to coagulate these forms in exciting and unconventional ways.

Sometimes we have straight documentary, then a stripped-back Brechtian satire, then an ambling pastiche, then a straight historical drama strewn with eccentric anachronisms, then a spoken digression, and finally – in a story about the little-known domain of competitive rural chaffinch song showdowns, a pastime apparently cultivated through the rise of suburban social housing blocks – a breathtaking mixture of all of the above.

It takes a long time to get a proper handle on Gomes’ tonal remit as well as his political motivations. Though the vignettes presented here are exclusively focused on the lives of impoverished Portuguese (an economic band which is said to have expanded massively under the spiteful, socially unjust machinations of the government), there’s a glibness and spry sense of self-satisfaction which percolates through the opening stretch. It feels like the director is lightly mocking his subjects.

So mercurial a talent is he, that the form constantly threatens to strangle the content, and whatever meaning is supposed to be drawn from the stories is sometimes obscured by the aggressively applied (but always welcome) technical capriciousness. Empathy is occasionally drained from the imagery, and we’re left with a guy who’s just playing his country’s deep-set collective woes like a cigar-box banjo.

And yet, these initial apprehensions are all but neutralised when considering the work as one giant whole – which it really should be. Gomes appears only vaguely interested in articulating blunt political statements about how an entire country can descend into the fiscal doldrums. And he does this by telling intimate, whimsical stories which speak of more broadly abstract concepts, primarily the ever-evolving interplay between poverty and culture.

The film sets out its stall as a prickly wallow in widespread trauma and oppression, only to later reveal itself as an exultant poem to the Portuguese populous and their daily strategies for muddling on though the omnipresent darkness. The existence of the film itself is an affirmation of that expression, that people look to the natural bounty of the landscape to procure their own forms of pleasure.

The adventure of finding out the subjects of each of these exotically sub-titled tales should not be spoiled here, as there’s always an intriguing question mark hanging over where Gomes will go next, and how he’ll go there. The narration is written in conspicuously ornate verse which secures a tight connection between the “age of antiquity” and modern times. It’s hard, too, to talk about aesthetics as Gomes adopts different styles (and film stocks) to suit the different subjects. The actors in the film re-appear in separate chapters, and in one case as a completely different character, again emphasising Gomes’ perpetual reminder that cinematic rule-breaking need not be an overtly ostentatious sport.

Taking stock of everything – this expansive, infuriating, lurid, shapeless, transcendent, resplendent quagmire of cinematic invention – one can’t help but be awed by how its spiralling, mad-eyed ambition is matched (and then some) by the sounds and images which have been captured for the screen. It builds and builds to an astonishing and heartbreaking crescendo, taking many secret backroads and byways in the process, and only by its final fames, which arrive to the heady strains of a child voice choir covering The Carpenters’ Calling Occupants, does Gomes’ colossal stores of human sensitivity truly shine through.

Arabian Nights is not a film which aims to make a difference, it’s a film which compassionately shares a cheeky cigarette with the people (and animals) who have already dedicated their lives to doing just that. A film about protest rather than a protest film. It’s an improvised, on-the-lam masterpiece, a lop-sided folk-art shrine, which finds genuine hope (rather than erroneous cinematic hope) within a context incomparable despair. Vive le Gomes…

Published 20 May 2015

The 2015 Cannes Director’s Fortnight strand opens with a magnificent miniature from Philippe Garrel.

The new feature from Arnaud Desplechin is a rite-of-passage masterpiece.

Enter the magical, mysterious world of Portuguese director Miguel Gomes’ three-part masterpiece.