“Somehow everything comes with an expiry date. Swordfish expires. Meat sauce expires. Even cling-film expires. Is there anything in the world which doesn’t?” Those lines of dopey contemplation come courtesy of the lovesick He Qiwu in Wong Kar-wai’s exuberant 1994 film Chungking Express as the recently dumped police officer, like so many Wong protagonists before and since, pines for that which is gone. It’s a reasonable question to hear from any resident of Hong Kong, a city that has long existed on a constant timer.

For most of the 20th century, that expiration date was 1 July, 1997, the day that would see Britain’s lease of the Hong Kong region come to an end, transferring sovereignty back to mainland China. In the two decades since, the number that many citizens of Hong Kong have been keeping a wary eye on is 2047, the year of expiration for the mainland and Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” framework that has allowed the latter territory to maintain its autonomy.

For some, the preceding 2046 will be a year charged with anxiety as the city hangs on the brink of change. For Wong, 2046 is both the number of a significant room at the heart of his immaculately composed 2000 film, In the Mood for Love, and the title of the director’s 2004 feature, a visually ravishing work that’s downright apocalyptic in its suffocating sense of dread and despair.

But let’s rewind a little. After all, that’s what Wong did for what is arguably his first great film. Forming an informal ’60s trilogy with In the Mood for Love and 2046, 1990’s Days of Being Wild is set at the start of a decade that would see Hong Kong’s economy flourish, securing its reputation as a leading Asian metropolis. It was also the decade in which a young Wong moved from the mainland to Hong Kong with his family amidst uneasy tensions that would soon manifest as the Cultural Revolution.

Fittingly, it is an era Wong presents through a green-tinted filter of nostalgia, imbuing its drama of young love and restless living with the seductive exoticism of a distant paradise. Naturally it can’t last, and so Days of Being Wild is replete with early examples of one of Wong’s favourite visual motifs, the clock, which has served as an ongoing reminder throughout the director’s career of the ceaseless forward march of time.

As the turbulent centre of Days of Being Wild, Leslie Cheung’s Yuddy lives like he hasn’t a moment to spare, assuming a self-romanticising ‘legless bird’ persona as he flies impulsively from woman to woman without ever stopping to land. His thematic counterpoint is found in one of his momentary lovers, Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung), a woman for whom their brief time together lingers on as a sorrowful and burdensome memory. These two personality types, one living aimlessly in the present and the other living hopelessly in the past, would be of continued interest to Wong in the years to come.

As the 1997 handover loomed ever closer, the worldview of the former ‘legless bird’ type would increasingly inform Wong’s work. 1994’s Chungking Express is a film characterised by restless, romantic energy and impending change in which Brigitte Lin plays a mysterious blonde-wigged criminal who speculates humorously on an unknowable future (“He may like pineapples today. Tomorrow, he’ll like something else.”) as she races against the clock. When her story concludes with the unnamed woman shooting her treacherous white drug baron associate, there is a satisfying sense of closure that one can’t help but relate to the region’s own western connections.

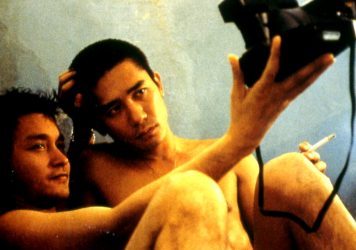

Nevertheless, by the time Britain’s lease reached its eleventh hour, the youthful romanticism of Chungking Express had congealed into something gloomy, bitter and defeated. The very first images of 1997’s Happy Together, which premiered mere weeks before the handover, are a series of close-ups of the British Hong Kong passports of Lai (Tony Leung) and Ho (Leslie Cheung) as the perpetually bickering couple makes the trip to Argentina, only to find themselves miserable, alienated and unable to return home. The emotional rootlessness and geographical displacement of these characters echoes the lonely ambivalence of a population who weren’t sure what home was anymore, with the Hong Kong identity currently in a state of flux.

Though Happy Together finishes on an optimistic note of acceptance and readiness for the future, as signalled by the final shot of a train pulling into the next station, Wong’s post-handover output saw the filmmaker withdrawing more than ever into a torturously pretty past. For the aesthetically exquisite In the Mood for Love, the impulsiveness of his earlier dramas has been stifled into an oppressive stillness and any last-minute sense of urgency is now replaced by painful regret. As a year at the edge of the unknown, 2046 lends its number to a room where nothing really happens between almost-lovers Su Li-zhen and Chow (Tony Leung) but rather things get agonisingly close to happening.

It is in the 2004 feature, 2046, however, where Wong’s obsession with the past reaches its operatic extreme. A work of nightmarish and self-consciously bombastic beauty, the film 2046 both observes and embodies the very human tendency to magnify memories over time, with the number itself appearing as both a room number and a fantastical location in an imaginary future where nothing changes. The amorous and idealised perspective of the unobtainable past found in Days of Being Wild is no longer just a profound stylistic means of presenting the story.

Now the fetishistic style is practically the story in itself, with a terminally heartbroken Chow seeing little of consequence beyond his own overblown emotions and memories as he resides despairingly in room 2047. It is perhaps no coincidence that 2046 would be Wong’s last Hong Kong-based feature for nine years, with the film serving as the hyperbolic endpoint for over a decade’s worth of thematic build-up.

Though it would be wrong to reduce any of the director’s richly layered features to this single sociopolitical allegory, the Hong Kong identity remains an important connective thread that runs through Wong Kar-wai’s greatest films. For those in the camp that consider Wong’s cinema to be all flash and no substance, understanding the important contemporary context of his works – with 1997 and 2047 as the critical years – could help to illuminate the unique emotional and thematic sensibilities by which one of the greatest living directors has composed some of his most melancholic and invigorating spectacles.

Published 18 Jul 2017

The Hong Kong master’s 1997 film is a deeply affecting portrait of a failing relationship.

In praise of the Hong kong adrenaline junkie and architect of the time-honoured bullet ballet.

By Amandas Ong

Will this enduring trope become obsolete as we move towards a less gendered worldview?