Four decades since Ralph Bakshi’s typically anomalous, post-apocalyptic animated feature Wizards premiered in the US, it’s time to take a closer look at what this film was trying to say – especially now that it means so much.

Bakshi is best known for his idiosyncratic, controversial animated films, starting with 1972’s Fritz the Cat, the first ever animated film to receive an ‘X’ certificate in the States. He maintained a loyal cult following with later films like Coonskin and Heavy Traffic while also gaining a wider appeal with slightly less risqué movies like The Lord of the Rings from 1978.

He almost single-handedly brought adult animation into mainstream focus, and he remains arguably its most influential practitioner. But regardless of whether you regard him as a true maverick or just plain irreverent, it’s never been more important to consider the reality of Wizards, as much as that sounds like an oxymoron.

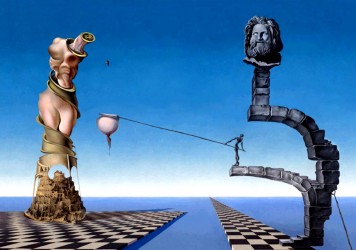

Wizards was Bakshi’s first fantasy film. As is the case with all his work, it is distinctively and stunningly animated, based off of original sketches Bakshi drew while he was still in high school. During production, British illustrator Ian Miller and comic book artist Mike Ploog were brought in to contribute designs and backdrops. Interestingly, Bakshi separated Miller and Ploog, with the pair working on specific groups of characters and settings due to their individual styles.

The film’s basic premise is an ancient war between Industrial Technology (the evil side) and Magic (the good guys). While the two sides are presented in fairly black-and-white terms, with the baddies painted quite literally as bumbling Nazis and the heroes consisting primarily of cheeky fairies and noble knights, this somewhat crude metaphor and does not dilute the film’s weirdness. It is a complex work that contains many messages.

Bakshi used traditional animation techniques, often incorporating repugnant images, to create intriguing tales that require us to really think about what we’re seeing on screen. In the case of Wizards, this was Bakshi’s creative way of dealing with a very real disaster which he saw unfolding. This is a film that could just as easily have been set in our own world, with live action stars and a more direct style. Granted, it wouldn’t be nearly as captivating or fun to watch, but Bakshi’s central idea – the sense of anxiety at the core of the film – would remain.

That in itself makes Wizards all the more fascinating when viewed today – especially for younger viewers whose seeming lack of interest in hand-drawn fantasy stories (and the people telling them) reflects the reality of Bakshi’s not entirely imaginary war.

CGI can be a wonderful thing in the right hands, but it’s a shame that traditional 2D animation has fallen so far out of favour since the advent of computer-animated feature filmmaking. The problem rests not with the technology itself but in the marked shift away from creating stories that stimulate and stretch our belief in magic and alternate realities.

It’s not that we’re losing Baksi’s war – in fact, we’re winning. We’re just fighting on the wrong side. And we can’t lose, because we have almost entirely stopped believing in our magical opponents.

Bakshi saw this coming 40 years ago, and nobody really took notice. In an age of cynicism, propaganda and fake news, it seems as if the more we buy into the notion that everything is coming undone, the more it will prove true. Because when people feel defeated, they stop fighting. Right now, creativity and imagination are the most powerful weapons we have. We’ve simply forgotten how to use them.

Published 9 Feb 2017

By Matt Turner

The recent Edge of Frame Weekender showcased bold contemporary visions and rarely seen masterpieces.

Director John Lamb reflects on the making of his pioneering short film featuring the singer-songwriter.

By James Clarke

In 1946 the moustachioed maestros embarked on the most ambitious project of their careers.