You might think that a music video directed by an Academy Award winner, created by a team that included a chief animator and director on The Simpsons, and staring Tom Waits, would be firmly cemented in pop culture history. But chances are you’ve never heard of Tom Waits for No One, a pioneering short film in which the American singer-songwriter performs ‘The One That Got Away’. That’s because it was released two years before the launch of MTV, and, owing to a run of rotten luck, has effectively sat forgotten for over 30 years.

In 1977, Waits made an appearance on the parody talk show Fernwood Tonight, hosted by Martin Mull and Fred Willard. His fingers skipped and glided across the piano keys in wriggly flutters and he began to growl the line, “The piano has been drinking”. The audience broke out in laughter, presuming his inebriated, grizzly rendition was part of a bit. After sitting down to be interviewed by the sarcastic duo he glugs on a bottle of booze and Mull says, “It’s kind of strange to have someone sitting here with a bottle in front of them,” to which Waits responds, “Well, I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy.” Director John Lamb was watching at home that night thinking, ‘Is this guy for real?’ Weeks later, Lamb went to see Waits play at The Roxy Theatre in Los Angeles to see for himself. “There were only about 30 people there,” he says, looking back, “but after about 10 minutes you knew this guy was for real, he was amazing. It was like performance art.”

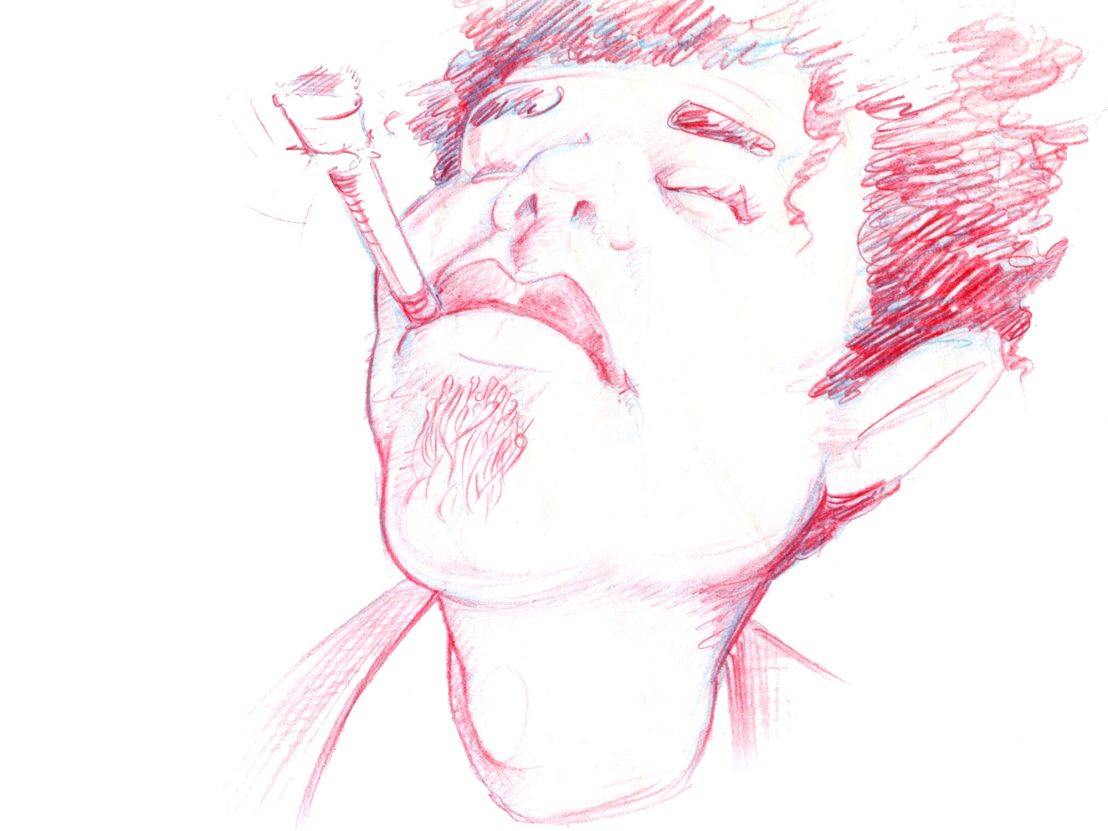

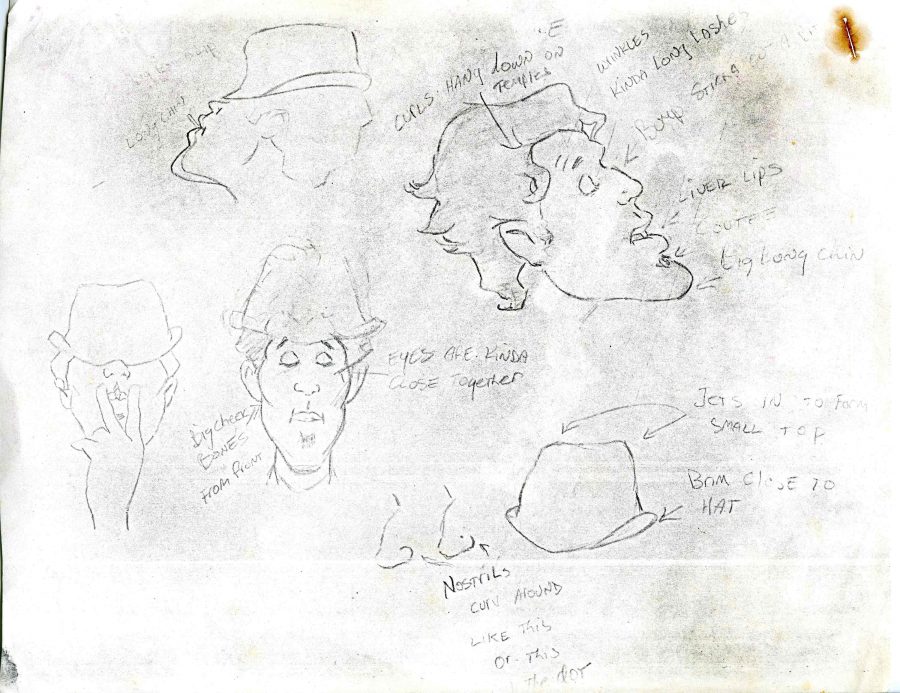

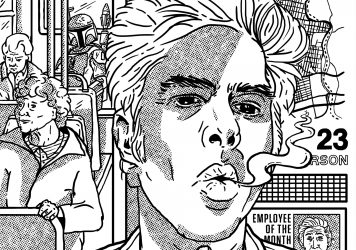

Lamb had recently invented a video rotoscope machine, which worked by taking live action footage, individually tracing each frame then converting them, by hand, into animation (an effect most famously achieved decades later by Richard Linklater on his digitised features Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly). He needed a test subject to see whether it was a viable product and Waits’ unforgettable performance at The Roxy – with his accentuated mannerisms and exaggerated bodily movements – instantly sprang to mind.

After making the call to Waits’ agent, Lamb and his team began storyboarding, with Waits occasionally checking in; he would sit and tinkle away on a piano as they talked. “He would bust out a few songs,” Lamb reflects, “we would have been star struck but back then he was just like us, just beating away on a piano in our studio in west LA.” Lamb continues, “I remember he would pull up in this ’66 T-Ford Thunderbird which said ‘Blue Valentine’ [the name of Waits’ 1978 album] on the back rear panel. It was stacked floor to ceiling with newspapers, there was only enough room in the entire vehicle for the driver. I visited his apartment sometime later and it was much the same.”

Jumping forward to the first day on set, Lamb recalls that Waits rocked up wearing “an old wrinkled suit and pork pie Stetson hat.” The director was praying that Waits would change into something else, only to see him emerge from his dressing room minutes later wearing a different but equally tattered suit. He then requested a pack of Viceroy cigarettes, and 45 minutes later, lit smoke in hand, Waits was ready to get to work. “Once we got started he pretty much directed himself,” remembers Lamb, “it was just a case of reeling him back in at the end of each take. He was responsive, easy and very professional, he did exactly what was asked of him.”

After ending up with 13 hours of footage taken from five cameras, Lamb and his team began the arduous task of animating a near-six-minute edited film by hand, frame by frame. “On a computer now you could do the whole thing in about two days,” says Lamb, “but back then it took 12 people six months to pull it off.”

Completed in 1979, Lamb and co were too early to catch the MTV wave, and had successfully introduced a new form of technology that was quickly superseded. “By the time the film actually came out the digital revolution was in full swing, so the machine became obsolete about six months after. It’s one of the only films ever done on the video rotoscope.”

Around the same time, Waits found love and quit the booze and the smokes and the women. “The film was Tom’s swansong of his old lifestyle,” suggests Lamb. “He wanted nothing to do with the warm beer and cold women period of his life anymore.” After a handful of promising initial screenings (including an award-winning presentation at the inaugural Hollywood Erotic Film and Video Festival), Tom Waits for No One was shelved, despite its star’s optimism about the film’s prospects: “I think it’s got a lot of style and it has a nice fabric to it, I think it’s got a big future but mine is a little bleak at the moment.” Lamb laughs heartily when reciting this quote, “What he said was exactly the opposite, his future was huge and ours ended right after the film was out.”

Lamb kept a record of the film’s production, newly released in the form of a limited edition scrapbook.

Published 29 Nov 2016

By Zach Lewis

The indie idol discusses Paterson, the musicality of movies and how Man Ray made films for his band to play along to.

By Lara C Cory

The Trent Reznor-produced score is being reissued for the fist time in 20 years.

Director Jim Jarmusch found the perfect creative kindred spirit for his surreal monochrome western.