When filmmakers make unexpected turns in their way of telling stories, it can be all for the creative good and when this detour occurs in the timeline of a filmmaker steeped in the tradition of the mainstream it’s especially interesting. In the mid-’40s, Walt Disney (who died 50 years ago this year), and who remains a fascinating example of studio head as auteur and concept-master, teamed up with Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí. These moustachioed maestros set to work on a mash-up of avant garde and mainstream sensibilities.

Walt Disney was a filmmaker of immense creative capacity who understood the different ways that entertainment can make an audience feel good about themselves and the world around them. Disney represented the apogee of pop movies just as Elvis and then The Beatles represented the apogee of pop music. Disney was an American entrepreneur excited by the possibilities that were to be explored through technological innovation and mass communication and his collaboration with Dalí offers up something of this sensibility. Animation historian Michael Barrier has written of Walt Disney that, “what made him different, and so much more exciting and interesting than most entrepreneurs, was that he emerged as an artist through realising his ambitions for his business.”

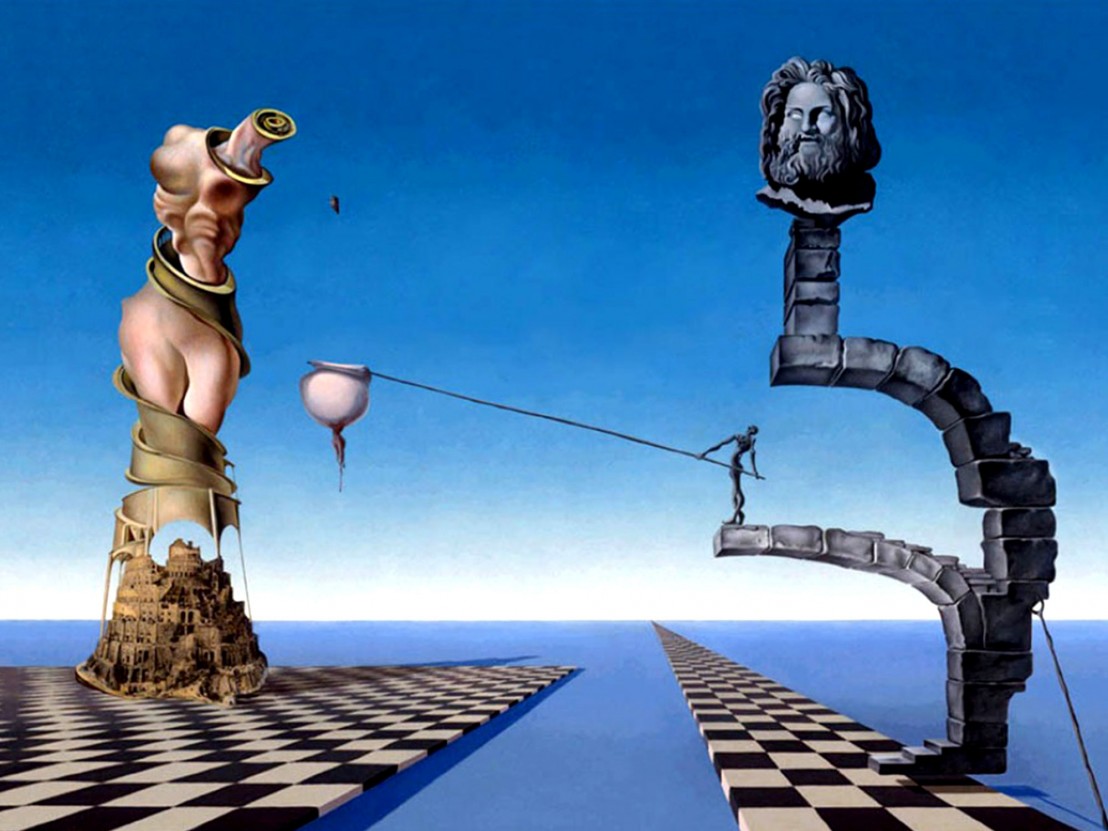

Like Disney, Dalí was interested in the fusion of the real and the unreal, and the animation studio’s reputation for creating the illusion of movement chimed with the dynamic that characterised so much of the landscapes that Dalí conjured in his work. He created an imagined place in which objects transform and mutate; enchanting and grotesque in combination. Of their collaboration, Dalí said that through its story he was attempting to explore a “magical portrayal of the problems of life in the labyrinth of time.”

Both Disney and Dalí had grown up in the early 20th century and both had been trained at art school before going on to innovate within their respective fields. Despite all of the good vibrations around the project, Destino was destined to never quite be completed… at least within the timeframe of the original collaboration. Indeed, decades would pass before it was eventually released in 2003. It’s also worth noting that the film was intended originally as a single short film within a feature-length portmanteau comprising several other short stories.

Work on Destino began in 1946, and key to the project’s initial undertaking were the contributions of two Disney studio artists, John Hench and Bob Cormack. Conceptual work on the short film lasted eight months, yielding just 17 seconds of footage, before being abandoned. It was not until the early 2000s, under the oversight of Walt’s nephew, Roy E Disney, that Walt Disney Studios integrated newly-drawn and rendered elements into the original footage. Dominique Monfery directed the final iteration of the film, adhering to the visual design and sequences laid out in Dalí’s archived storyboards. Original notes for the film described it as a “love story” between a dancer and a baseball player who was also a manifestation of the god, Chronos and the screen-story had been inspired by a Mexican song by Armando Dominguez, a relatively obscure source for Walt for whom the energy between music and movies was deeply entwined.

The finished film was shown in 2003 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The film showcases Dalí’s images and designs, imbuing them with additional, animated fascination, taking familiar Dalí images and applying them to a sensibility familiar to us from Disney’s Fantasia. Dalí considered Disney a great American Surrealist and, in promoting the start of work on Destino, Dalí had described the film to the press as being “a magical exposition of the problem of life in the labyrinth of time.” Consider how different in tone Walt Disney’s set-up of the film’s premise was, describing it as “just a simple story of a girl in search of real love.”

The Dalí-Disney superteam collaborated with great energy. However, Disney did express caution: he wanted to be perceived as an artist but his previous art-film project, Fantasia, had not been a commercial success. Despite their energised collaboration, Dalí and Disney abandoned their version of Destino, leaving about 80 pen and ink sketches completed and various items of development and conceptual art, including paintings in oil and in watercolour, to eventually be rediscovered decades later.

For all of his caution about it, Destino points to Disney’s interests and commitment to refining and evolving classical animation and to making the mainstream work as a conduit for something less expected, less familiar. Although never really a director in his own right, beyond a very early career attempt, Walt Disney continues to stand as one of a number of animation auteurs whose work offers evidence that the medium might just be the highest form of cinema.

Published 7 Aug 2016

By Matt Packer

Legendary animator Floyd Norman tells the inside story of how a Disney classic was made.

As Disneyland turns 60, we turn back the clock to gauge the cultural impact of the most enchanted corner of the Magic Kingdom.

Gorgeous original artwork spanning three decades of the iconic animation studio.