“Experimental animation is the term we use because others won’t do,” explains artist and animator Edwin Rostron, creator of Edge of Frame, a blog turned event series focusing on the more marginal forms of experimental film and animation. “People get quite bogged down with terminology, trying to define what is and what isn’t animation. A lot of people who make work that you could call animation don’t really see it that way. It’s maybe part of a painting practise thats evolved into moving image, or drawing brought to the screen.” Rostron’s latest event, Edge of Frame Weekend, reflected this interdisciplinarity, featuring diverse programmes of work made by artists arriving from all sorts of directions and films that came in wildly varying shapes and forms.

Some of the most captivating films were those that utilised direct animation techniques to emphasise the materiality of film as an object or the physicality of the processes, objects and surfaces involved in their production. The most dramatic of which may be camera-less film Mothlight, for which Stan Brakhage fastened moth wings, plant life and other natural detritus to strips of editing tape. When ran through a contact printer onto 16mm film and projected, his film conjures rapidly flickering, dancing lifeforms from this dead material, reanimating the frozen pieces as if by magic.

In a similar vein, for Landfill 16 Jennifer Reeves took discarded 16mm material from another project, buried it underground until it began to decompose, before exhuming it and hand painting abstract universes over the disrupted forms, creating cosmic majesty out of decay. Both films interrogate what it might mean to work with hand-processed, physical materials; finding the sublime by reinterpreting static, ugly materials and making them dynamic and expressive.

Two more recently made films also focused on extracting the ecstatic from ordinary sources, using the fundamental properties of light as a basis for finding new ways to create visually satisfying experiences out of simple means. Stephen Broomer’s Queens Quay blends a wash of radiating light out of layered strips of brightly hued celluloid, the rapidly varying images fusing in and out of each other to create beautiful geometric forms that reverberate alongside a gently rapturous optical score. In Something Between Us, prismatic light effects are drawn from ordinary objects, Jodie Mack photographing jewellery, water and other reflective materials at angles that produce glitzy prisms of coloured light, then cutting them into a kinetic, synaesthetic ballet. In both, plain objects are animated in a fashion that uncovers their secret glimmering beauty, water made into wine.

Elsewhere, some other connecting factors could be drawn between the best works in a wide reaching, quality offering. Many films used patterning as their mainstay, drawing splendour out of animation’s ability to morph and mutate repetitive elements, but two digital maelstroms made 35 years apart did so particularly effectively. In modern artist Peter Burr’s Green | Red recognisable visual elements emerge from a radiating stream of pixelated forms, coloured forms blending hypnotically in and out of a monochromatic pixel mass whilst a pulsating techno soundtrack guides the increasingly frenetic tide.

Seventies computer art pioneer Larry Cuba’s precisely structured Two Space features similar monochrome pulsations, as a short programmed sequence shows a white dotted chain whirling and swirling against a black field, choreographed neatly to the rhythmic sounds of ancient Javanese gamelan music. Produced twelve times, each repeated pattern tessellates mesmerically into the other, the simplicity and synchronicity producing an entrancing effect.

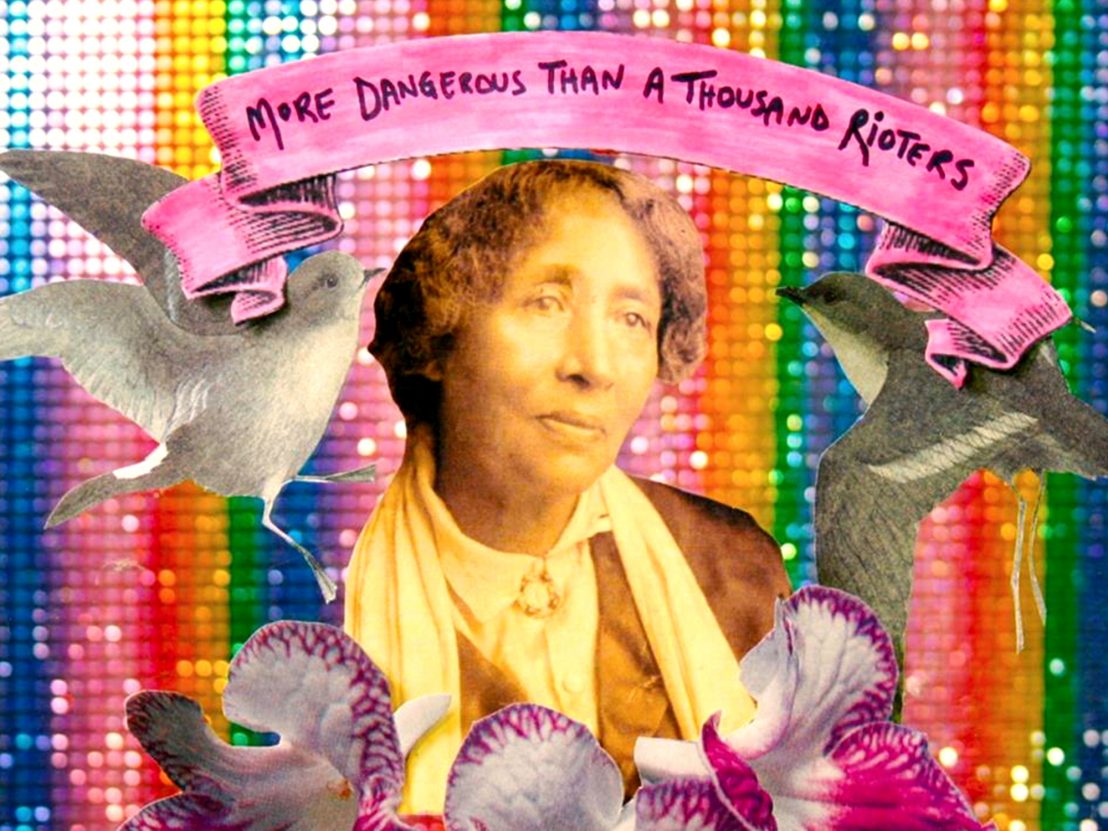

A lot of the best work also used collage to impressive effect. Stuart Hilton’s mixed media work Save Me uses a cacophonous array of found sounds and images as the basis for abstract exploration, collating them together like a song by The Books. Scrawling and painting hundreds of visual interpretations to accompany this cavorting aural canvas, his film is chaotic but imaginative. Similarly Robert Breer’s Trial Balloons mixes photography, film and animation, often all at once, drawing and pasting material over recorded scenarios to add extra flavour to the real. A kind of unpredictable home-movie montage, Breer’s oddity is joyful, unpredictable and exuberant, packed with the colour, humour and texture of a life made more interesting by art.

Other highlights were (relatively) more traditional, involving stylistic or narrative shifts applied to traditional hand drawn animation techniques. Jonathan Hodgson’s Nightclub draws upon sketches made in Liverpool drinking holes, depicting the social struggles that take place within subcultures, visualising the anxious position of the individual within a crowd. With a expressively neurotic art style and brilliant, imposing music produced by the artist himself, Hodgson’s film pulsates with the atmosphere of the exaggerated scenario it depicts.

A tonal opposite, Yoriko Mizushiri’s Futon too has a singular, distinctive art style, but one that’s surface is as soft as the juddering edges of Hodgson’s film are hard. Gently flowing cozy imagery drifts in and out of abstraction, as Mizushiri’s sleeping protagonist dozily and sensuously awakens from a deep slumber, a dream logic drifting into her waking reality. A film of soft tones and clean lines, Futon is subtle, yet commanding, rich with nuance and meaning despite it’s muted, soporific tone.

“The word animation has baggage that can put people off, or make them think of certain things,” says Rostron, What is clear from Edge of Frame is that the connotations we can have are often wrong, and the limitations we impose are just that, limiting. For Rostron, “there is a general lack of familiarity with animation that leads to it being miscommunicated.” As a practitioner himself, he understands how this could be done better than most, and sold out screenings testify to his success. Delving into the many offerings of Edge of Frame demonstrates the rewards of taking a chance, of welcoming strange ideas and experiencing new things.

Published 21 Dec 2016

By James Clarke

In 1946 the moustachioed maestros embarked on the most ambitious project of their careers.

Director John Lamb reflects on the making of his pioneering short film featuring the singer-songwriter.

With Snoopy and Charlie Brown back in cinemas, Nick Pinkerton explores the legacy of Charles M Schultz and other innovative cartoonists.