An angel falls in love with a woman and decides to become human in order to be with her. With only this sketchy premise to go on, you could be forgiven for dismissing Wings of Desire as pure schmaltz (City of Angels, the reductive and embarrassingly expositional 1998 Hollywood remake starring Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan is a case in point). Arguable worse, if you saw just the first half of Wim Wenders’ 1987 film you might think it to be nothing more than a morose and pretentious catalogue of quotidian suffering.

But this would be to ignore what the film becomes: a playfully postmodern masterpiece with a modernist sense of humanity, a poem to the city of Berlin, a Hegelian musing on selfhood and, yes, a love story. More than any of this, though, Wings of Desire is a uniquely life-affirming celebration of humanity.

Introducing West Berlin to us through the eyes of angels – their perspective marked by black-and-white film stock and an ability to hear the thoughts of the human characters we encounter – the film opens with the depressing and sometimes distressing inner monologues of the city’s inhabitants as they fret in their apartments and cars, on planes, bicycles and balconies. We’re then introduced to two of the seraphim themselves, Cassiel (Otto Sander) and Damiel (the recently departed Bruno Ganz), sitting undetected in a car showroom convertible.

Reading from a notebook, Cassiel begins to recite the times of sunrise and sunset, the levels of local rivers and the events which occurred on the same date 20, 50 and 200 years before: a plane crash, the Olympic Games, the first balloon flight over the city. In this moment we learn how angels experience time, as something amorphous, eternal and ultimately meaningless. They then begin to speak of more poignant, personal things, and it is these all too human moments which punctuate the infinite, giving form and meaning to both time and life. “I don’t need to beget a child, or plant a tree,” says Damiel, the film’s hero, when he confesses to daydreaming of experiencing the world as humans do.

Life, to the angel who sees history from beginning to end, is not about legacy, but engagement with the ongoing present. As he lists the things he might like to feel – to have a fever, to be excited by the line of a neck, or an ear, to come home like Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and feed the cat – a seemingly self-serious piece of cinema becomes a celebration of small things.

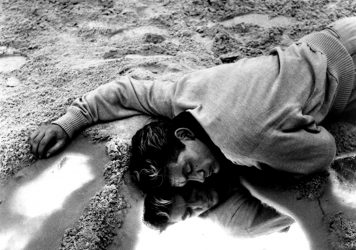

The colourless world that represents the angels’ sensual deprivation is like a blank canvas, and the poetic screenplay that Wenders co-wrote with Austrian novelist and poet Peter Handke paints it with the vividness of human experience. When Damiel encounters the dying victim of a motorcycle accident in perhaps the film’s most moving scene, he soothes him by turning his thoughts to memories of life: near-palpable images of bread, wine, riding a bicycle with no hands, and many more worldly things.

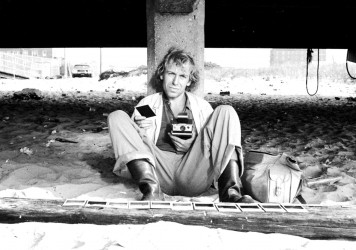

When he encounters Peter Falk (played by Falk himself), who used to be an angel himself and so can sense our hero’s presence, the late Columbo actor explains the joys of rubbing one’s hands together for warmth, drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes, all of which Damiel discovers for himself later. When Damiel eventually becomes human, the film bursts into colour – the hues of which he must ask a stranger to define – the sudden saturation of the screen reflecting that of the character’s senses.

We first glimpse colour, though, when Damiel meets Marion, the beautiful and sometimes melancholic trapeze artist he falls head over heels in love with. As she undresses in her trailer following a rehearsal at the raggedy travelling circus that will soon shut down and leave her alone in West Berlin, Damiel stands by curious but sexless, listening attentively to her inner thoughts as he does the film’s other human characters. When the scene switches briefly to colour, indicating we are seeing Marion now from the human perspective Damiel longs for, she puts on her dressing gown and, taking three oranges from a bowl, begins to juggle. Play is a prominent theme here.

From Marion’s many circus scenes to Damiel’s innocently direct interactions with children – who are tellingly able to see him both in his angelic and human forms – the film idealises all things ludic and childlike because they represent a sense of wonder at the world, a way of learning to be human through experience. In the penultimate scene, where Marion dances on a rope that Damiel holds while he muses on the pair’s first night together, the conclusion of their love story is not mutual possession, but a state of novel shared experience and thus constant play.

Wings of Desire is neither so saccharine as to suggest that love can overcome suffering or death – quite the opposite: it’s only through submitting to time that Damiel is able to love at all – nor does is it claim that all experience is good. By portraying characters who are conscious but unable to experience the world, the film invites us constantly to marvel at the very fact of living and feeling at all, at the poetic possibilities of “swimming near the waterfall,” “the dear one asleep in the next room,” “the night flight,” of love and sex. We share in Damiel’s exultant self-consciousness when he tells us, at the film’s end, “I know now what no angel knows.”

Published 20 Feb 2019

By Adam Scovell

The British filmmaking pair’s 1948 masterpiece is an elegant ballet of myth and fairy tale.

How Wim Wenders’ 1970s Road Movie Trilogy captured the romantic lure of American culture.

The French filmmaker’s haunting 1950 work fluidly blurs the line between technology and magic.