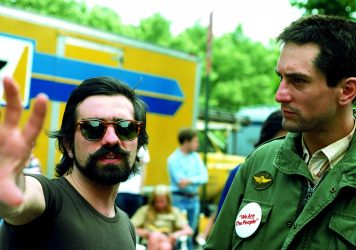

The year 1967 is rightly lauded as a landmark in American cinema. The likes of Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, In the Heat of the Night, and The Dirty Dozen ushered in a new era of mainstream film-making which unashamedly dealt in graphic themes of violence, sexuality, and race. Yet amid the sound and fury of these provocative films, the arrival of another pioneering film-maker is often overlooked. It was in November that year that a young graduate of the New York University premiered his directorial debut. Fifty years ago, at the Chicago International Film Festival, the world was introduced to Martin Scorsese.

Originally screened under the title I Call First but now commonly known as Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Scorsese’s debut may not be as well regarded as his later work, but it’s influence is every bit as pervasive. Shot on a minuscule budget and cobbled together over several years, the film would provide a touchstone for the rest of the young director’s pioneering career. Drawing upon his own experiences, Scorsese’s first film is an uneven but complex meditation on Italian-American identity, faith, and masculinity – all themes which have continued to preoccupy his work for the last half century.

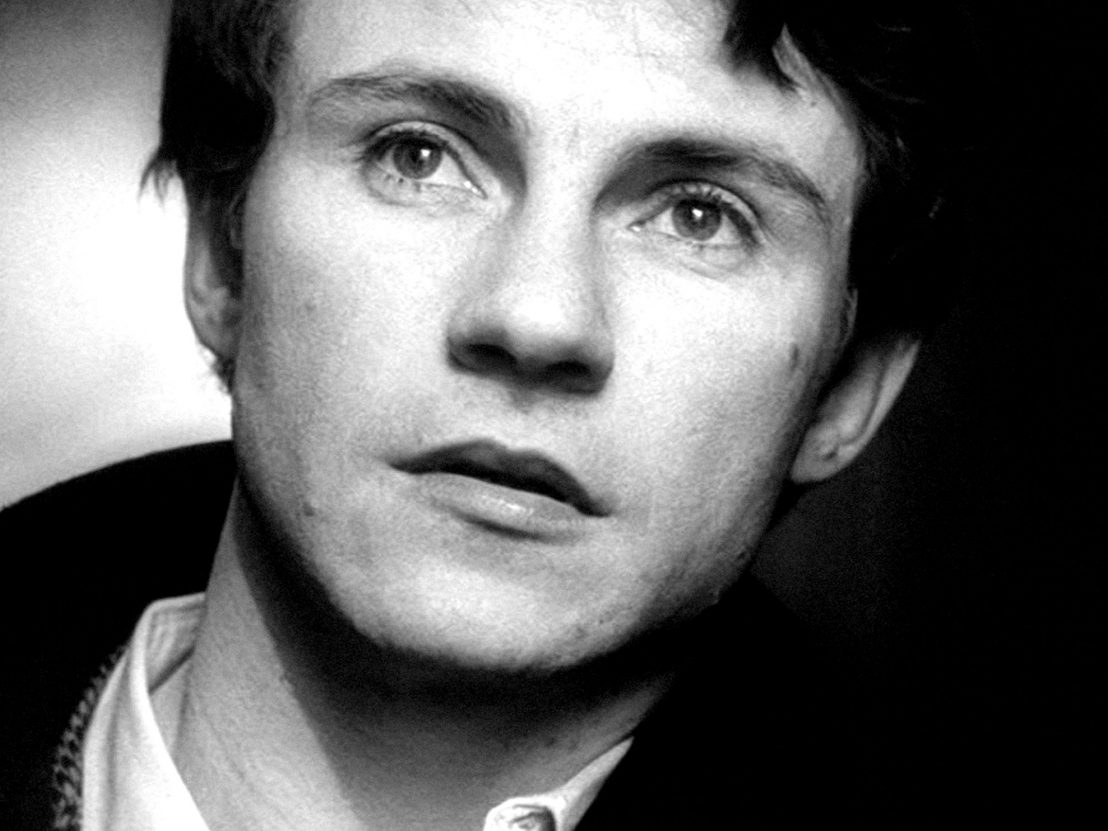

The film started life as a student project in 1965, curiously titled Bring on the Dancing Girls. Harvey Keitel, then working as a court stenographer, was enlisted for his acting debut in the lead role of “JR”. The resulting first cut was a largely plotless, 65-minute effort which followed JR and his friends as they goofed, got drunk, and pursued women across Little Italy. In Scorsese’s own words, the initial screening was “a disaster” and his work was “universally hated”.

The following year, Scorsese procured the finance necessary to extend the scope of the film and introduced a romantic side-plot. Keitel was reluctantly brought back for reshoots and Zina Bethune cast as his girlfriend. These scenes were shot on lower-quality film stock and spliced with the existing footage, the only giveaway being the fluctuating length of Keitel’s hair. It was this version of the film, now titled I Call First, which screened at Chicago in 1967.

Despite the film’s stilted production, Scorsese’s talent was quickly recognised. Roger Ebert instantly described the film as “a great moment in American movies”, and later reflected that it had announced “the arrival of an important new director”. Nevertheless, the film did not receive a wide distribution for over a year, when it was picked up by exploitation distributor Joseph Brenner and a graphic sex scene was hastily added in order to court the exploitation market. The new title was taken from the song by The Genies which plays over the end credits.

Like many of his contemporaries, Scorsese’s early films owes a great debt to the French New Wave. His erratic editing style and monochrome photography echoes Jean-Luc Goddard, but Scorsese’s subjects are distinctly American. With this debut film, the director chose to cast a light upon the environment and culture in which he’d grown up, and in doing so gives a profoundly authentic impression of the Italian-American experience.

Keitel’s JR is a thinly veiled substitute for Scorsese himself. In one charming scene, JR meets a girl on the Staten Island Ferry and proceeds to clumsily deliver a spiel on the brilliance of John Ford’s The Searchers. In this way, JR and his friends are totally detached from the mafioso stereotypes which often define Italian-Americans on-screen. Gangsters are peripheral figures, and the closest thing to a shoot-out is a slow-motion play-fight over a pocket-sized revolver. The director would later proudly state that Who’s That Knocking At My Door “was the first film to show what Italian-Americans were really like”.

Central to the world in which Scorsese’s characters live is the contradictory role of religion, perhaps unsurprising considering that the director once flirted with joining the priesthood. Catholic guilt is a predominant theme throughout Who’s That Knocking at My Door, specifically the relationship between JR’s conservative upbringing and the sinful reality of his existence. This is a contradiction he projects onto the women in his life, whom he divides into two, distinct groups; “nice girls and broads”. The pure, virginal image he creates of his “nice girl” girlfriend is disrupted when she confides that she was once raped by a past boyfriend. Unable to accept that it was not her fault, he dismisses her as a “whore” and shuns her.

JR’s warped understanding of female sexuality ultimately leads him to sacrifice his potential happiness, but this is rooted in the toxicity and confusion of his own desires. He fantasises about casual, uninhibited sex with experienced women, but refuses intimacy with his own girlfriend because he believes her to represent an idealised image of celibate romance and Christian marriage. His expectation that women conform to the artificial standards of a “nice girl” or a “broad” merely act as a justification for his paradoxical yearnings.

This confused duality between “improper” desire and “proper” romance crops up in many of Scorsese’s male protagonists. In Taxi Driver, Travis Bickle is thwarted in his attempts at romance because he is unable to distinguish between the two, choosing a pornography cinema as the venue for a second date. For Jake La Motta in Raging Bull, sexuality and violence go hand in hand. He represses his physical desire in order to save energy for boxing matches, but later his impotency causes him to lash out violently against his loved ones. And in The Age of Innocence, Newland Archer is torn between his love for his chaste fiancé May Welland and the rebellious divorcee Ellen Olenska. Clearly, the self-destructive nature of masculine sexuality is a topic which has continued to fascinate the Manhattanite director.

All this, of course, would come later. What Who’s that Knocking at My Door does illustrate, however, is that Scorsese never saw the world as one of heroes and villains or clear-cut morality. Despite its humble origins, this film offers a uniquely ambiguous perspective on mid-’60s American life and the conflicting human impulses which drove it. As Roger Ebert predicted in 1969, Scorsese would go on to explore these ideas with greater depth and polish in later films – in many ways, 1971’s Mean Streets feels like a high-gloss remake of this initial effort. Like so many other young directors, Martin Scorsese was knocking on the door of Hollywood, and it wasn’t long before he was answered.

Published 15 Nov 2017

An incredible video essay looks at divine presence in the work of this American master.

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.

By Dan Einav

The director’s 1993 period drama is just as devastating as the likes of Taxi Driver and Goodfellas.