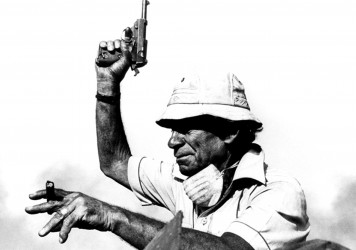

Some time in the 1990s, Samuel Fuller pulled the famed director Richard Linklater aside after a screening of Dazed and Confused, and, in his cigar-cured baritone, said: “Your movie concerns a human emotion I am particularly interested in… hate.”

Hollywood studios never gave him the chance to make a movie about hate until he was in his seventies. But when they finally let Fuller off his leash, he produced one of the most controversial movies of the ’80s. Today, as current events are once again inviting many Americans to re-evaluate their attitudes towards race, violence and reform, White Dog, deserves a second look.

The film follows a young white actress named Julie (Kristy McNichol), who accidentally strikes a white German Shepard in the Hollywood Hills and upon resuscitating him adopts him. Soon, she learns that the dog’s violent tendencies follow a disturbing pattern. The dog is a “white dog,” conditioned and programmed to attack black people. Seeking to exhaust all options before putting the dog down, Julia finds herself at Noah’s Ark, an animal-training centre, where a black anthropologist, Keys (Paul Winfield), offers to take on the project of reprogramming the dog.

The story was adapted from Romain Gary’s novella of the same name. Gary was married to the actress Jean Seberg, who was also an activist with ties to the Black Panthers, and the couple adopted a German Shepard which they later discovered had been trained by the Alabama police to fight blacks. In response to targeted harassment by the FBI due to her association with the black power movement, Seberg eventually died by suicide in 1979. Undoubtedly influenced by this dark chapter, Gary’s original story carries a far darker and more cynical attitude toward race relations than Fuller’s screenplay, culminating in a vengeful black animal trainer reprogramming the dog to attack white people.

“Beyond the film’s technical prowess, White Dog’s greatest feat is its treatment of black heroism.”

For Fuller, Gary’s story had a deep message at its heart but its surrender to defeatism was unacceptable. Instead the director used the simple allegory of a canine diseased by racism to explore themes that we still talk about today: Is racism inherent or curable? Is reform attainable? If so, who bears the burden for working on reform? Julie’s understandable affection for her pet, who she knows bears no animosity towards her but is dangerous towards others, becomes a venue to explore idea of white guilt and shame of association.

However, beyond Fuller’s dialogue, and beyond the film’s technical prowess – Ennio Morricone’s singular score manages to blend fear and melancholy, while the early use of Steadicam captures the dizzying vortex of violence – White Dog’s greatest feat is its treatment of black heroism.

The thematic traps which Fuller escapes were as firmly ingrained in Hollywood back then as they are now. For decades the industry has shown its bias in the type of race-related movies it endorses: the only stories about race deemed worth telling are those in which people of colour reenact their socially-imposed subservient roles, or experience transformation through their association and alliance with white people (a trope commonly referred to as the “white saviour” narrative). Here and there, the industry makes space for historical dramas or biopics which, although often more admirable in their approach, continue to reinforce a limited vision of African-American history and experience.

White Dog inverts this structure. In Fuller’s screenplay, the only notable white perspective is that of white naïveté, and Kristy McNichol’s performance successfully delivers that. By contrast, the character Keys (Paul Winfield) is presented as a black hero whose arc does not concern his own personal struggles with racism; instead, he embodies the only possible cure for the white dog’s affliction. This emphasises that racism should be viewed as a problem for its perpetrators and not those subjected to it.

Winfield’s portrayal of stoic patience in the face of blind, senseless hatred creates a transformative perspective on racial antagonism: one in which the black perspective on racial hatred is shared solely from the position of power.

Published 17 Jun 2020

By Rich Johnson

Samuel Fuller’s murder mystery captures the fear and paranoia which beset postwar society.

By Tom Bond

In BlacKkKlansman, the director dramatises real-life events in order to make his point.

By Liam Dunn

From Shock Corridor to White Dog, the late director’s work has lost none of its social relevancy.