With absolute conviction, a black man pulls a piece of cloth from under his shirt, “A sign of the invisible Empire…” he points to a potent symbol that signals the baptism of the Ku Klux Klan. “KKK. It’ll catch on quick.” In this place he is the Grand High Wizard, “If Christ walked the streets of my hometown he’d be horrified. You’ve never seen so many black people cluttering up our schools and busses and cafes and washrooms! I’m for pure Americanism! White supremacy!”

Tim Robbins once asked director Samuel Fuller about this infamous scene and he revealed that he hadn’t written a single word. Lifted from congressional records, this piece of dialogue is, in fact, a direct quote from an American Congressman, subverted by Fuller through the only black character featured in his 1963 film, Shock Corridor.

As a crime reporter and political cartoonist during the 1930s, Fuller tackled this scene with a tabloid mentality; his approach less about rationality than the constant quest for truth which stemmed from his keen awareness of social issues. Shock Corridor is as much a reflection on the mindset of the individual as it is that of American society. In his search for truth, whether a crime or the brutal reality of war, the real battle for Fuller was, “Between the insane and your own sane mind.”

Set against a backdrop of simmering racial tension and released a year before the Civil Rights Act was passed into law, Fuller’s film tells the story of journalist Johnny Barret (Peter Breck) who has himself committed to a mental institution in order to solve a murder. Barret intends to infiltrate three witnesses, each one reflecting a disturbing part of America’s societal background and history, using the experience to win the Pulitzer Prize.

The patients are Stuart (James Best), who imagines himself as a Confederate after being brainwashed, the aforementioned black man masquerading as a white supremacist, Trent (Harrry Rhodes), and Boden (Gene Evans), an atomic scientist scarred by the devastation of nuclear power who has now regressed to a childlike state.

Fuller’s microcosmic approach naturally leant itself to such a confined setting. The corridors themselves symbolise America’s fenced-in mindset, with postwar paranoia at its most potent. Here, a person may snap at any moment, reflecting prevailing social tensions of the time as well as conservative anxieties over the growing women’s liberation movement and sexual revolution. As Johnny enters a room of nymphomaniacs, their carnal, zombie-like behaviour calls to mind George A Romero as much as Masters and Johnson, as Johnny’s screams, for once, hamper his internal monologue.

Normal? Johnny once gagged on the word. Confident that he would retain his sanity, ironically it is his love and conviction that leads to his inevitable breakdown. Seemingly pre-empting the assassination of President Kennedy, Shock Corridor isn’t a film about a murder so much as the slow death of America. Fuller understood that for those rendered insane or mute, it was impossible to speak out. In his America there are no heroes or cowards, only a sad, inevitable truth which very few people were prepared to accept.

Shock Corridor is released on 2 September via The Criterion Collection.

Published 2 Sep 2019

By Lynsey Ford

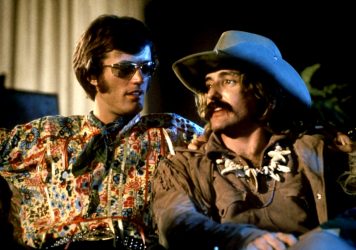

Fifty years ago, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper birthed arguably the defining film of America’s counterculture era.

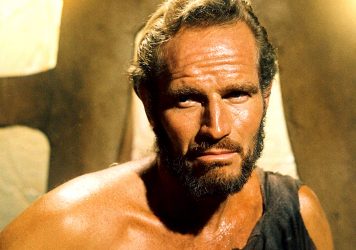

Franklin J Schaffner’s satire was a response to an era of social upheaval.

By Liam Dunn

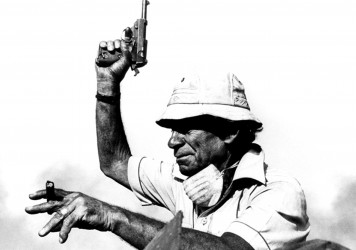

From Shock Corridor to White Dog, the late director’s work has lost none of its social relevancy.