Richard Burton once claimed that Where Eagles Dare was conceived at the request of Elizabeth Taylor’s two sons, who wanted to see their stepfather in the sort of rollicking adventure film he would normally shun. It seems fitting, then, that Brian G Hutton’s World War Two actioner has earned notoriety as the quintessential “boys’ own adventure”. Or, less charitably, the ultimate “dad movie”.

Despite its uncool reputation, Where Eagles Dare still endures 50 years after its initial release – Steven Spielberg once named it as his all-time favourite war movie, while the code phrase “Broadsword calling Danny Boy”, as uttered by Richard Burton several times in the film, still surfaces in the unlikeliest of places, from Doctor Who to Rebekah Brooks’ trial during the News of the World hacking scandal. The simple explanation for this widespread affinity is that Where Eagles Dare is a far more subversive and important work than it is often given credit for. Drawing inspiration from the New Hollywood American filmmakers of the late 1960s, it employs a radical approach to violence, gender politics and history which was perfectly pitched for the counter-culture generation.

By 1968, action-adventure films in a similar mould to Where Eagles Dare had been popular for decades, arguably beginning with pulpy wartime propaganda pictures like John Farrow’s Commandos Strike at Dawn. Author and screenwriter Alistair MacClean was a prolific figure in the genre, and as such his script for Where Eagles Dare is an admittedly rote affair.

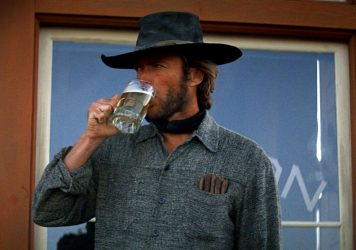

Ice-cold intelligence operative Major Smith (Burton) leads a team of slightly aged British agents and a token American, Lieutenant Schaffer (Clint Eastwood), into Bavaria to rescue a captured allied General from a mountaintop Nazi fortress. From there, the story becomes almost laughably convoluted as a procession of traitors and double agents are uncovered during the second act, followed by a full hour of non-stop action. On the page there isn’t much to distinguish Where Eagles Dare from its innumerable peers, but its execution is both thrilling and genuinely subversive.

The first action sequence occurs at the 59-minute mark, and it’s from this point that the film’s portrayal of violence begins to bend the expectations of the genre. Classic war adventures like The Guns of Navarone and the cynically sadistic The Dirty Dozen had been typically bloodless affairs; Nazis are riddled with bullets and blown to pieces without any obvious physical damage. In contrast, Where Eagles Dare takes its cue from the iconic violent finale to Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, where every bullet wound explodes gratuitously with blood.

The film’s callous approach to violence echoes the spaghetti westerns which catapulted Eastwood to stardom in the mid-’60s. As Lieutenant Schaffer, he dispatches regiments of Wehrmacht infantry with a clinical, super-human deftness, reminiscent of The Man With No Name dealing with bandits in the Wild West. Notably, the immensity of violence is at odds with Alistair MacClean’s original novel, in which the protagonists take care to avoid any loss of life, even to the extent of rescuing an unconscious Nazi from a burning building. Evidently, such clemency was not considered appealing to cinemagoers in 1968 – the film has a body count of over 100, with Eastwood himself killing more people than in any of his other films.

It’s not only the violence that reflects the era in which the film was made. The two female leads, played by Mary Ure and Ingrid Pitt (herself a real-life Holocaust survivor) are both very much products of the late ’60s. They are written as quick-witted and independently minded agents, and at least as adept with a machine gun as Eastwood. Nevertheless, they repeatedly find themselves subject to uncomfortable ogles and leering remarks from their male co-stars, both heroes and villains. This conflict between strength and objectification is an embarrassing paradox, but commonly found in films of the era (1968 also saw the release of Jane Fonda sexploitation classic Barbarella).

These flourishes of ’60s counter-culture give Where Eagles Dare a subversive edge which helps to explain its lasting appeal and influence. When Eastwood turns his submachine gun on a horde of unsuspecting Nazis, it’s difficult not to cast your mind forward 40 years to the bloody climax of Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds. Indeed, Where Eagles Dare even takes a similarly loose approach to historical authenticity, from Eastwood’s bouffant hairstyle to the inexplicable appearance of post-war Bell 47 helicopter. It’s a fantastical and stylised vision of World War Two which was quite radical for its time.

Where Eagles Dare serves as a bridge between two eras of American action cinema – the bloodless fun of The Guns of Narvarone and the unflinching brutality of Dirty Harry. With this in mind, it feels apt that the film brought together Hollywood veteran Richard Burton and relative newcomer Clint Eastwood. While Eastwood would soon become one of Hollywood’s hottest properties, Burton was never again to star in a major box office hit. Let’s hope his stepsons were happy.

Published 22 Sep 2018

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.

This controversial 1973 western ranks among the director’s finest works.

Alan Ladd’s mysterious stranger in town fundamentally changed the way audiences believed in heroes.