Ten minutes before the end of Thief, Frank (James Caan), the titular safecracker extraordinaire, leaves his new family home on the outskirts of Chicago and drives away – but the camera lingers on the house. Seconds later it’s reduced to a smouldering heap, torn apart by two raging fireballs.

At this point, Frank’s luck has long since run out. What was supposed to be one big score for Chicago crime boss Leo (Robert Prosky) has turned into ongoing employment. With one friend already dead, Frank’s new wife Jessie (Tuesday Weld) and their adopted son are now under threat. But it wasn’t Leo that rigged those charges. No, Frank set those explosives himself – the same explosives he uses to blow up his downtown dive bar, before torching every last motor at his used car dealership. As an ex-convict facing a return to enforced servitude, Frank instead razes his entire life to the ground. Or rather, his life as capitalism has defined it.

In his 1981 debut narrative feature, director Michael Mann scrutinises the American Dream as it is sold to blue-collar workers. Played with an apathetic swagger by James Caan, Frank is the logical end point of a capitalist society that exploits manual labourers, selling them a white picket-fence fantasy they’re ultimately excluded from. It’s telling that the annihilation of the house’s picture-perfect facade is the film’s climactic sequence, Mann shooting each cathartic explosion from multiple angles.

Prior to the events of the film, Frank was incarcerated for petty theft – sentenced to two years but serving 11, trapped in a cycle of violence perpetrated by the guards. Worse than that, he was fed a bootstrap-pulling narrative: that if he worked hard enough on the outside, he’d make enough money to make up for lost time. Mann frames this logic as intensely tragic; the belligerent crook trying to steal sand back from the hourglass.

Mann shoots the Windy City as Frank experiences it: dingy blues clubs, neon-stripped liquor stores and rain-soaked streets. He may own two “respectable” working class businesses, but he works mostly at night – typically deemed a sign of criminality or unsociable factory work. At each stage, Mann ties Frank’s criminal process back to blue-collar manufacturing, luxuriating in the nuts and bolts mechanics of Frank’s moonlit robberies by holding on tight close-ups of boring drills and shorn rounds of metal from the vault door. Frank might not be stealing from the rich to give to the poor, but there’s shades of Robin Hood about the way he seizes the means of production.

Likewise, all of Frank’s criminal colleagues have a background in manual labour, from electrician Barry (Jim Belushi) to mentor Okla (played by working-class country music icon Willie Nelson). When Frank needs sophisticated safecracking equipment for the big heist, he doesn’t turn to a hi-tech laboratory à la James Bond – he goes to a metalworking factory, where the faces and hands are the same dusky blue as the overalls and the machinery, and the lone white suit is singled out for mockery.

Things start to go south when Frank is drawn in by the promise of steady employment and easy money. Introducing himself as “The Bank”, Leo is the embodiment of America’s capitalist ills: gluttonous, rapacious, and with no moral code to speak of. He gives Frank a nice, clean heist and finds him an off-the-books adoptive son. But once you’re part of the system, you have to play by the rules; something Leo reminds Frank of with increasing venom.

Mann personifies these rules quite literally though the police. Much like the guards Frank faced in prison, the officers in Thief are corrupt to the core, shaking him down for their “10 points”. They bug his house and his car, and before Frank knows it he’s imprisoned again – working to line someone else’s wallet and facing beatings if he falls out of line. His response when Leo asks why he doesn’t abide is practically Marxist: “I can see my money is still in your pocket, which is from the yield of my labour.”

Earlier, Mann has Frank and Jessie hash out their romantic prospects in that most true-blue of settings, the American diner. Frank lays out his past, his philosophies and, most candidly, his desires, visualised in a dream board collage assembled from newspaper clippings. That simple card, with its cobbled-together vision of a happy family, was fundamentally mis-sold. Later, as Frank spurns Jessie prior to blowing their house sky high, he can’t explain himself properly. “It’s not what was supposed to be,” he says simply, palming her off with the last of his cash. “It’s not what was supposed to be.”

Buried in that bemused declaration is the realisation that this idealised life hasn’t been lost – it was never attainable in the first place. When it comes time for Frank to burn it all down – freeing himself from Leo and the bonds of capitalism – Mann uses the glow of the flaming cars to illuminate a scrunched-up card Frank has discarded from his wallet. Without the meaning afforded to it by Frank, it’s just trash, barely distinguishable from any other scrap of paper. Another lost dream for the blue-collar worker, turned to kindling for the fire.

Published 27 Mar 2021

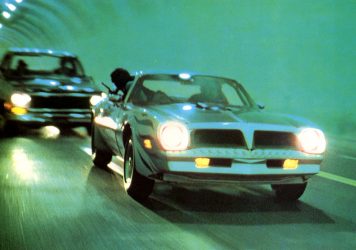

Walter Hill’s cult film is full of intense car chases and silent antiheroes.

By Soham Gadre

Jules Dassin’s blacklisting from Hollywood led him to create this superlative 1955 crime thriller.

By Tom Williams

Bret Easton Ellis and Mary Harron’s caustic vision of ’80s consumerism is sadly back en vogue.