Tall and broad, with a mop of curly golden hair and a megawatt grin, Burt Lancaster was an astonishing specimen; that he spent much of his twenties as a circus acrobat just enhanced his formidable figure. Frequently he seemed almost like an alien trying to go undercover as a human: smile a little too wide, movements a little too big, line readings invested with an intensity that could knock the unsuspecting straight off their feet. This was not a man who readily disappeared into a role – whoever he was playing, he was dazzlingly and energetically Burt Lancaster. Within the confines of his star persona, however, he was able to find multitudes, especially as he grew older.

Lancaster’s athletic prowess was exhibited spectacularly and often during his first decade and a half in Hollywood. He made nine films with his old circus friend Nick Cravat, the best among them being the rambunctious pirate movies The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and The Crimson Pirate (1952), which allowed the pair plenty of space to execute their gymnastic feats. Trapeze (1956) utilized Lancaster’s circus skills even more explicitly, positioning him as a trapeze artist caught in a love triangle with fellow performers Tony Curtis and Gina Lollobrigida.

Even when the role didn’t specifically call for acrobatics, Lancaster’s extraordinary physicality and boundless energy lit up his work across various genres. His ebullience made him a natural fit for snake-oil salesmen, such as Bill Starbuck, his grifter in The Rainmaker (1956). A silver-tongued charmer who promises to bring rain to a drought-ravaged Kansan town, Lancaster’s Starbuck is a one man fireworks display, leaping and dazzling and talking a mile a minute, charming Katharine Hepburn’s Lizzy despite the obviousness of his hucksterism. In her reaction to Lancaster, Hepburn becomes our audience surrogate; she’s not really taken in, but she’s entranced by the show. Ultimately, choosing to believe in this extravagant, ridiculous man works wonders for her fragile self-esteem.

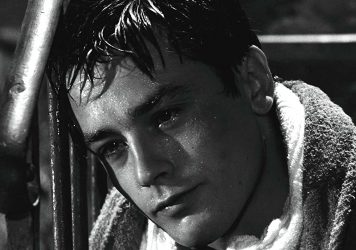

Lancaster could be just as effective when he reined in his vigour, crafting characters of coiled-snake stillness. There’s no better example than Sweet Smell of Success (1957), when he played Walter Winchell-esque gossip columnist JJ Hunsecker, who holds the little life of Tony Curtis’ walking ulcer of a press agent in his big, meaty hand. While Curtis bobs and weaves, walking as fast as he talks, Lancaster’s measured movements (Hunsecker deems few people even worth turning his head to look at) tell us all we need to know about his unnerving power. He used his stillness to a similarly destabilising effect as a mutinous army general in Seven Days in May (1964).

You might think an actor whose persona was so linked to their immense physical presence would start fading from view as the years caught up with them, but advancing age bought Lancaster’s work another dimension.

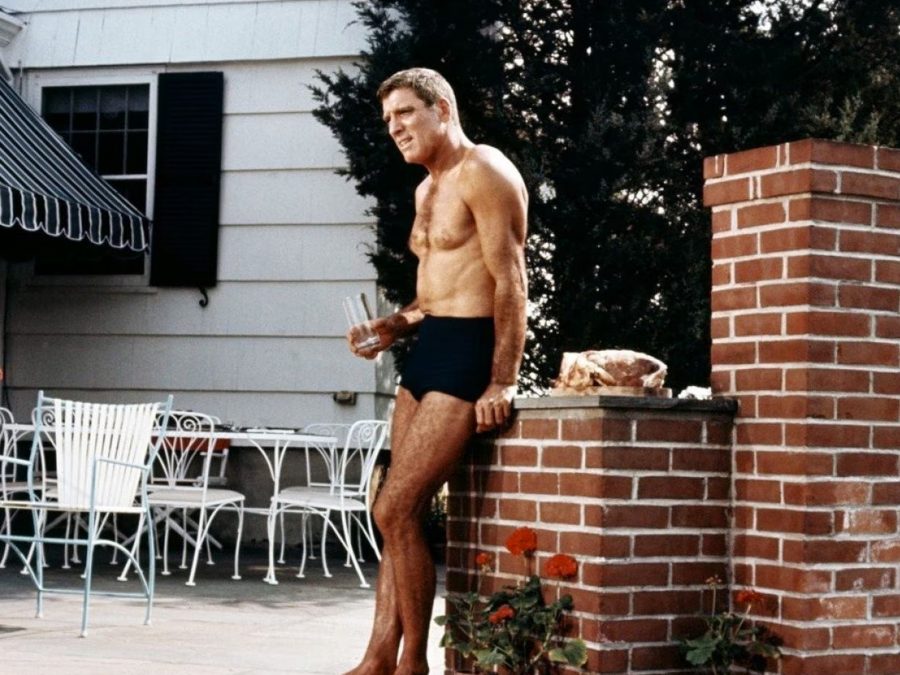

He still had an astonishing build during The Swimmer (1968) – which was shot when he was in his early fifties – but the story of an arrogant man slowly realising his best days are behind him is made more poignant by the fact the audience had watched Lancaster age over the last two decades on screen. That he spends the whole movie only in swimming trunks gives him nowhere to hide, and makes the eventual crumbling of his self-deception feel extra visceral.

Similarly, Lancaster’s fumbling tryst with Deborah Kerr in The Gypsy Moths (1969) is impossible to watch without remembering younger versions of the two rolling around on the beach in From Here to Eternity sixteen years earlier, where they created one of the sexiest love scenes of the studio era. The weight of time lends their later, clumsier affair, with both actors well into middle age, a dramatic potency far beyond what’s on the page.

Over a decade later, in Louis Malle’s Atlantic City (1980), Lancaster sports a full head of white hair – as many people refer to him as ‘old man’ as they do his character’s real name, Lou. An ex-hood whiling his days away looking after the bedridden widow of an old associate, his grey life is re-invigorated after he meets Susan Sarandon’s much younger Sally, the estranged wife of a petty con, and falls awkwardly back into a life of crime.

Lou is subjected to various humiliations throughout Atlantic City, largely stemming from his still considering himself as much of a player in the boardwalk’s underworld as gangsters half his age, whilst absolutely no-one else does – a late-movie pronouncement “I’m dangerous!” is sodden with desperation. Lancaster plays these delusions of grandeur with the wild look in his eye so familiar from his work in the forties and fifties, but what lends his performance in Malle’s movie its special texture are the piercing moments of clarity that come between these delusions, where Lou realises exactly what he is and how far he has fallen. Lancaster gives these moments both a palpable ache and a wounded dignity, ultimately winning immense grace for a character who could so easily have been nothing but a joke.

In Local Hero, Lancaster again enriched a potentially cartoonish character, delivering a supporting turn full of the off-kilter romanticism that personified both the movie, and his own long career.

As Felix Happer, the Texan Big Oil boss who sends an underling (Peter Riegart) to a remote Scottish coastal village to buy up the land for a pipeline, he should be the villain of the piece – but the film refuses to assign him any malignancy. He’s not even all that interested in making money for his company; it’s the stunning Scottish skies that most fascinate the amateur astrologer. Whereas Riegart’s pragmatic city dweller takes a while to fall under the spell of the natural world, we get the sense that Happer was born with his head in the clouds… far above them, in fact. When he finally arrives in Scotland at the end of the movie, setting down on the beach at dusk, he lands in a helicopter that might as well be an alien spaceship.

Lancaster was almost seventy at the time of filming, with the gymnastic pyrotechnics of his early career many years behind him. Nevertheless, as he waxes lyrical about his love for the stars, the sparkle in his eyes demonstrates with magnetic clarity how the unearthly charisma of his youth never dimmed, only deepened.

Published 19 May 2023

The French screen idol is at his most open and vulnerable in Luchino Visconti’s 1960 crime drama.

His manipulative housekeeper at the centre of Joseph Losey’s 1963 film is a sly subversion of his star persona.

By Elisa Adams

This classic Doris Day musical from 1953 is filled with catchy, surprisingly progressive show tunes.