Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer prize-winning 2016 novel ‘The Underground Railroad’ tells the story of the secret routes and safe houses that existed for enslaved African-Americans to escape to the free states and Canada. It conceives of an alternate reality where a literal rail network actually exists. We follow the teenaged Cora (Thuso Mbedu) in her quest for freedom from the numerous inventive cruelties of America.

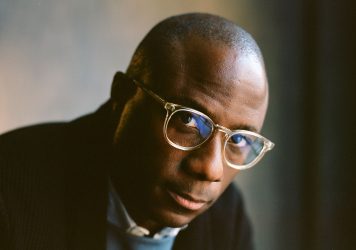

In a groundbreaking 10-part series for Amazon Prime, Oscar-winner Barry Jenkins masterfully elevates this epic and complex tale. His adaptation is revelatory. Often enough, depictions of the slave experience on screen have reduced slave owners to caricature arbiters of extreme violence, unrecognisably cruel and easy to dismiss, with enslaved people presented as little more than receptacles of that violence.

In this series, Jenkins imbues every member of the principle cast with a profound humanity that seeps into the bones. By synthesising the skills of his trusted regular collaborators, composer Nicholas Britell and cinematographer James Laxton, and perhaps most importantly the nuanced and compassionate performance from lead actress Mbedu, Jenkins is at the height of his powers when fluidly mutating the style and tone of every scene to align with Cora’s brittle interiority.

In the first episode, Jenkins establishes exactly what this series will and won’t be. Opening with a surreal and eerie sequence of Cora falling backwards through time, we land on the Randall plantation in Georgia, during a meagre birthday party the enslaved are throwing among themselves. Caesar (Aaron Pierre) asks Cora to run away with him. She dismisses his request out of hand and rejoins the festivities that are abruptly interrupted by the slave owning Randall brothers.

The thick Southern accents, fancy canes and general unease the Randall’s inspire is familiar. The routine of masters humiliating the enslaved and punishing them for not fulfilling their role as jester, and the whipping that follows – though obscured by night and shot at a distance – is familiar. Jenkins reintroduces us to this well trodden path in the first instance, only to diverge from it entirely throughout the series.

Later on in the episode we are introduced to Ridgeway (Joel Edgerton), a slave catcher whose reputation precedes him. He is returning a runaway to the Randall plantation with his accomplice, 11-year-old freed slave Homer (Chase W Dillon), who at times appears like an apparition standing at four feet tall in a three piece suit and bowler hat, tallying up the price of fellow Black people for his boss. Terrence Randall (Benjamin Walker) is hosting a tea party, and the graphic flaying of the runaway provides the entertainment.

An English guest, Mr Churchill (Mark Ashworth), remarks that he doesn’t understand how one can eat given a man is being whipped in front of them. Since the English exported their brutality to the Caribbean, the practises of the Antebellum South appear tacky by comparison. This is the first and last display of gratuitous violence in the series, and it feels self-referential to the on-screen format as Jenkins makes it explicit who these displays are for: white spectators, and they can either revel in or retract from them.

To tell a story about slavery for the screen, there will always be a tension as to who this story and these images are for. Does the need to persecute a modern audience override the desire to present enslaved peoples with dignity? Do fetishistic displays of violence achieve either of these goals, or do they become salacious fodder for depraved racists? The body of the runaway is set on fire and the enslaved people on the plantation are commanded to watch. The tea party continues. This is Cora’s cue to flee.

On Cora’s epic journey, she encounters the innumerable innovative ways Black people are dehumanised in America. From episode to episode Jenkins isn’t drawing parallels, but highlighting continuations of this treatment through to the present. At every new location (demarcated as stops on a secret train line), Cora is suspended in hope, somewhere between fear and faith. She swallows her grief and tentatively embraces affection where she can find it.

The railroad itself occupies a liminal space: pitch black; only accessible via trap doors; and running on its own schedule. At various stages Cora uses it to slip through the clutches of forced sterilisation, christian fanaticism, murder and recapture. We are told that Mabel (Sheila Atim), Cora’s mother, is the only person who has managed to evade Ridgeway’s recapture. The humiliation she brought on his reputation is what fuels his obsession with recapturing Cora. Mabel’s escape is what fuels Cora’s belief that freedom is worth everything, even abandoning your child for. Themes of matrilineal trauma and healing are delicately woven into the series, which arrives at a poetic and heartbreaking resolution.

A more prominent theme in the series’ latter episodes is its searing condemnation of Black capitalism, and the astute assertion that freedom treated as a commodity is not freedom and, under capitalism, any notion of freedom is nebulous. The fact that The Underground Railroad can be so broad in scope yet so formally intimate and textured is a testament to the skill of its creator and cast. Jenkins has proven time and again that he is the maestro of fusing love and suffering, acknowledging that life cannot exist with the absence of either.

The series shows a deep respect for the lives and experiences that would have been lived, without ever sanitising the horrific conditions that were endured. Mbedu channels Cora’s spiritual anguish with the kind of heart-wrenching sorrow and grit that most actors could only hope to achieve in their career.

Trauma and violence exist in every people’s history. What many works fail to realise is that recapturing the cruelty doesn’t have to require retraumatisation. Cora is more than the violence meted out on her. She saves herself time and time again because it’s recognised that the will of the enslaved had to be stronger than any of us can fathom.

Published 14 May 2021

The Moonlight director sits down to pick apart his wonderful James Baldwin adaptation, If Beale Street Could Talk.

Our Obama Era Cinema series continues with Caspar Salmon reflecting on the vitriolic online backlash to recent progress in Hollywood casting.

By Luís Azevedo

This new video essay explores the director’s evocative use of colour, from Medicine for Melancholy to If Beale Street Could Talk.