Few directors explored the human condition as intimately as the late Jonathan Demme. Whether revolutionising the concert documentary with Stop Making Sense, or delving into the homophobia of Philadelphia, his films immersed us in conflict, often removing the artifice between audience and character. It felt like at any moment, we could reach out and touch them, talk to them, connect with them. This effect, while aided by strong performances, was largely due to Demme’s groundbreaking use of subjective camera angles.

“The most powerful shot of all,” Demme said in a 2015 interview with Plugged In, “is when you put the viewer right in the shoes of one of the characters so that they are seeing exactly what the character is seeing.” And starting with his offbeat romantic comedy Something Wild from 1986, that’s precisely what he did. Instead of staging actors on opposite sides to give the impression of spatial continuity, Demme bucked tradition by sticking them in the centre of the frame and matching their eyeline with the camera. This imbued a sense of urgency to films like Something Wild or Married to the Mob, as characters appeared to be bearing their soul directly to the audience. When we saw them, they saw us.

But nowhere was this device more effective than in Demme’s 1991 masterpiece The Silence of the Lambs. While the film itself marked a thematic departure from his previous work, the central relationship between FBI agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) and imprisoned serial killer Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) proved too compelling to pass up, as it enabled him to explore common tropes through his subjective lens. Or as he put it, a chance to “create a scariness” that felt unique.

This is evident from Starling’s initial meeting with Lecter. Veteran agent Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn) warns her not to reveal anything personal during their conversation, saying “Believe me, you do not want Hannibal Lecter inside your head.” Because of Demme’s camera placement, it appears as though Crawford is not just saying this to Starling, but to the audience as well. Taken by itself, the shot could just have easily broken the tension of the scene and been distracting, but the fluidity with which Demme uses it ensures that we never leave the realm of the story. It is also one of the few times Demme uses subjectivity on a supporting character, as most of it occurs between Starling and Lecter, or between the audience and the film’s antagonist, Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine).

When Lecter finally appears, he’s shown, fittingly, through Starling’s tentative point of view. Initially, she observes from the safety of a medium shot. As the scene progresses, however, the camera pushes in on Lecter’s face, his piercing eyes transfixed on Starling, drawing her – and by default, the audience – closer to him. It gets to the point where the only way one can break free of his gaze is to look away from the screen. In doing this, the film quite literally traps its audience, as the simple act of viewing means that we succumb – as Starling does – to Lecter’s psychological games. Without realising it, we’ve let him inside our heads.

The third, and perhaps most unexpected use of subjectivity are the scenes involving Buffalo Bill. While little is revealed about his character in terms of backstory, it is these brief glimpses, passed off as home video recordings, that tell us all we need to know. Demme forces us to leave Starling behind and explore the darkest corner of the film alone. Once again, the artifice of cinema is removed, and what we discover in this corner is a human being – damaged, no doubt, but still capable of emotions like happiness and frustration. By refusing to demonise Bill, like so many screen killers in the past, the film creates a more compelling, and, consequently, more frightening experience.

Never for a moment does Demme allow us to veer into escapism or passivity. He makes sure that we remain alert, active participants – when Lecter hisses at Starling, we too recoil in fear. When she’s assaulted by Buffalo Bill in the film’s climax, we share in her disorientation. Beneath all the violence and gore, The Silence of the Lambs excels at creating empathy between audience and character, and that’s precisely why it remains Demme’s defining film and one of the greatest psychological thrillers ever made.

Published 6 May 2017

By Tom Watchorn

Paranoia, mystery and moral ambiguity abound in David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock’s masterpieces.

Never has on-screen magic been so compelling as in the director’s now 10-year-old passion project.

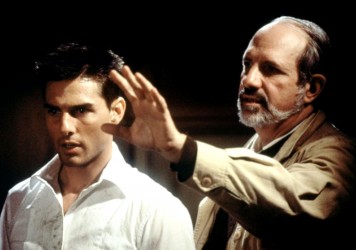

Twenty years ago Brian De Palma and Tom Cruise ushered in a new blockbuster era.