A sense of archaeology persists when exploring the films of Orson Welles. For a large part of his career, control of his projects was precarious at best, resulting in multiple versions of some films and questionable surviving versions of others. Welles’ second (and last) picture for RKO, The Magnificent Ambersons, is overshadowed by the most complex of these histories.

Adapting the Pulitzer-winning novel by Booth Tarkington, Welles was once again given the chance to explore memory and nostalgia as in his previous film, Citizen Kane. The Magnificent Ambersons suffered severe cuts while Welles was working in South America – it is arguably the film he lost most control of. Yet considering its questioning of perception, the past and memory, the film’s uncertain production seems somewhat fitting.

The nostalgic narrative follows the ups and downs of the Ambersons, a rich Midwestern American family. Isabel Amberson (Dolores Costello) is courting the inventive but foolish Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotton) before she leaves him after an embarrassing incident for the rich but cold Wilbur Minifur (Don Dillaway). They live their lives in a hollow way but have a child called George (Tim Holt).

Through the years, Eugene becomes a successful motorcar entrepreneur but still yearns for Isabel, who is trapped in the loveless marriage. The grown-up George, in spite of having fallen heavily for Eugene’s daughter, Lucy (Anne Baxter), forcibly and obstinately keeps his mother and Eugene apart until tragedy strikes the families. All are forced to face the horrors of the coming Motor Age and the changes it equally enforces upon their town.

This is possibly the most frustrating instance of Welles losing control of a project. Though the version of the film that exists today is still detailed and brilliant, there’s little doubt that the latter half and the infamous reshot final scene render it uneven. Yet there’s much to ponder in the loss of almost 40 minutes of footage, and how this plays out in the film’s overall examination of nostalgia giving way to a harsh reality.

In both versions, reconciliation between Eugene and George is finally met when the latter is severely injured by a car, some years after Isobel’s death. In the new ending shot by the studio and edited by Robert Wise, a closer bond between Eugene and Isabel’s sister-in-law, Fanny (Agnes Moorehead), who long harboured feelings for her sister’s lost love, is suggested.

In Welles’ comparatively stark original, Eugene was to visit Fanny in her new, rundown communal home, the gulf between them set in stone; rendering the accord between the two men bitter-sweet and cementing further the loss of Isobel, whose love Eugene can now only feel via reconciliation with her son. The tacked-on ending seems contradictory to the film’s descent from chocolate-box, sepia-tined visions of the past to the busy, unforgiving modern world. For a film that opens early on with Welles’ famous voiceover suggesting, “In these days, they had time for everything,” the frantic cut-up of the ending’s resolution unbalances the darkness and is deeply ironic.

But memory is key to the film, and perhaps this ending acts in its own way as a unique, more accurate presentation of misremembering; more true to the fallacies and hypocrisies of our own retellings and that of the characters. This misremembering could be Welles’ own as it feels most apparent in his voiceover. Such is the gloom that builds as the years go by, it would be in line with the character of the narration to turn away from this sadness, if only because the motorised future looks so unforgiving.

The symbolic motorcar is shown to augment almost everything and everyone around it. Snowy vistas of sledging and frosty kisses in carriages are soon replaced by shots so dark the characters appear in silhouette. The car is rather like the furnace at the end of Citizen Kane, burning those final dreams of an innocent, compacted world, albeit in years rather than minutes.

Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons are similar in the way they deal with memory. Both look back and then slowly travel forwards in search of where things went wrong – that moment where the mansions became desolate and the towns dirty. Welles once suggested of The Magnificent Ambersons that, “The basic intention was to portray a golden world – almost one of memory – and then show what it turns into.” Citizen Kane is similar, again moving from the innocence of a snowy past into the more brutal, mechanical world of power and reach.

Unlike Charles Foster Kane, however, Eugene Morgan recoils in quiet horror at the impact his ideas have had on the world around him. He is denied his own Rosebud right up until the point at which it is lost to him forever; only gained momentarily when he finally forgives the person who has kept him away from it. In either ending of the film, this would have been so, though is more saccharine in the version that was ultimately released.

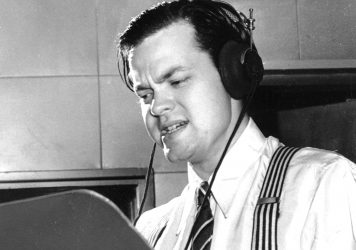

This was not the only time Welles adapted the narrative. Three years before, he turned it into a radio play for The Campbell Theatre with Walter Huston playing the lead. Even in this version, the ending is still lighter than the cold distance of Welles’ original film ending, arguably resembling the re-cut version more. It suggests that the compromise was not entirely alien to the narrative. However, the film’s many other edits, including one infamous cut in the middle of what was a detailed and accomplished single tracking shot, accumulatively weaken it.

In spite of the adversity the film faced throughout its production, Welles’ roaming camera still resulted in one of the great classics of American cinema. It’s certainly proof of the director’s talent – even having been forced to relinquish control to a large extent, The Magnificent Ambersons is still a masterful work, whether we remember those sepia visions from days long since past accurately or not.

Published 16 Feb 2019

A passible Welles hagiography which offers very little that you won’t easily find in an Encyclopedia.

By Adam Scovell

Revisiting the iconic director’s work every 10 years, from Too Much Johnson to Touch of Evil.

By Tom Graham

Read the remarkable story of the director’s ill-fated passion project, 400 years on from the death of Miguel de Cervantes.