The history of animation is checkered and complex, but the first name to come up is usually Walt Disney Studios – Mickey Mouse’s creator is more often than not heralded as the leading figure of the art form. One of the most well-known outings for the mouse overlord is Steamboat Willie which, in 1928, was one of the first pieces of animation to be synchronised to music. As the studio experimented with different stories and characters, they produced Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, their first animated feature film. While it’s indisputable that Disney’s films were landmark achievements, there was a filmmaker who changed the game well before them.

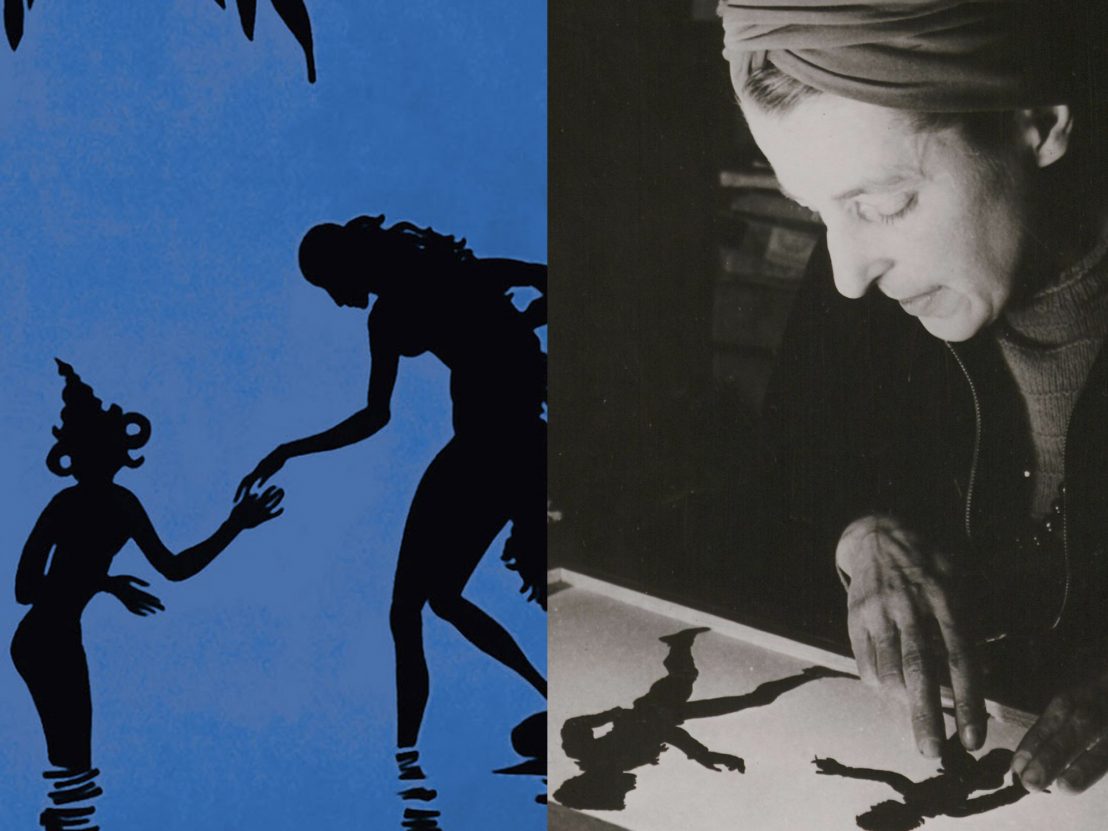

Enter Lotte Reiniger, the creator of the oldest surviving feature animation. As a child the German filmmaker was obsessed with puppets. She made paper figures of fairy tale characters, and cut out figures for hours to perform plays for her parents. Born in Berlin in 1899, Reiniger was part of the first generation to come of age with cinema, inspired by films like Georges Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon. In her mid-20s, Reiniger set out to create her own movie. She chose to adapt the Middle Eastern folk tale compilation One Thousand and One Nights, using stop-motion to bring her handmade paper cut-outs to life.

The result was the feature-length The Adventures of Prince Achmed, which was released in 1926. More than a century later the film still dances with vibrancy and colour, lifting the fairy tale out of the books and on to the screen. It depicts the adventures of Prince Achmed as he navigates unexpected magical creatures and malicious sorcerers. The way Reiniger’s characters move is entrancing yet disturbing, as they bend their bodies in superhuman ways and conjure exaggerated expressions from paper alone. Watching the film often feels reminiscent of an Escher painting, with scenes twist effortlessly into optical illusions. It is easy to forget that it was created only with practical effects. Reiniger was inspired by Chinese shadow puppetry, using simple blocks of colour to tell a story through more abstract imagery than traditional 2D animation. Instead of manipulating the puppets to move, she used the technique of stop-motion animation.

The process is famously grueling even for filmmakers now (Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio took two and a half years to complete) and, although Reiniger was not the first to use the technique, she did pioneer its use for longer projects.

The film was well received, much to the surprise of many of Reiniger’s fellow animators. The art form had only been used for quick visual tricks, such as the short film Humorous Phases of Funny Faces. It seems hard to imagine now, where animated films often run as long as live action (the recent Spider-Man: Across the Spiderverse Part One clocks in at 135 minutes). Reiniger’s film also experimented with animation techniques that made the industry evolve faster than ever. She created a predecessor to the multiplane camera, a technique used to create a sense of depth. Disney used a similar method in Snow White 10 years later, and is often credited for its invention. Even though her film did well, Reiniger’s success was slowly overshadowed by the larger Hollywood studio. An indie female filmmaker never stood a chance against the American juggernaut and their mouse mascot.

Even as animation reached wider audiences with Disney’s releases in the 1930s, women in the industry were still unable to reach the same positions as men. They were usually only allowed to work in the Inking and Colouring department, which required precision and patience to paint every frame individually. If they tried to climb the career ladder, they were met with a stern rejection letter stating: “Women do not do any of the creative work in connection with preparing the cartoons on screen, as that work is performed entirely by young men.”

Over 100 women, known as ‘colour girls’, worked on breakthrough animated films for the studio including Snow White and Pinocchio. Next time you watch one of these films, take a closer look at the credits. You will see a small smattering of women credited for working in production, but that does not even scratch the surface of the amount of women who coloured in those beloved frames. It wasn’t until 1941, with the possibility of male animators being enlisted into the army was on the cards, that women were able to train as animators at Disney Studios. Finally, talented filmmakers such as Retta Scott could show the world of animation what they were made of.

Reiniger died 41 years ago this month, and her legacy is only starting to be recognised. If she walked into an animation studio today, things would look very different, with female filmmakers , in theory at least, being given the same opportunity as their male counterparts. Domee Shi became the first woman to solely direct a Disney feature with Turning Red in 2022, depicting dorky teenager Mei as she grapples with her newfound ability to transform into a red panda. But outside of Disney’s shadow, many female animators are getting to tell their own bizarre and beautiful stories. Nora Twomey’s The Breadwinner and The Final Exit of the Disciples of Ascensia by Jonni Phillips are just a few examples of films starting to get female animators taken seriously.

But this slow and long overdue progress is not enough. Only one woman has won an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature (Jennifer Lee for co-directing Frozen), and duo Domee Shi and Becky Neiman-Cobb snatched a win for Best Animated Short with Bao in 2018. Mainstream studios often fail to recognise the talent of female animators and directors, who are forced – like Reinger a century ago – to instead find opportunities in indie filmmaking. Instagram and Youtube are rife with brilliant female animators, free to explore themes away from the rules of mainstream animation, and demonstrate the breadth of talent out there just waiting for a wider platform. To name a few, stop-motion animator Andrea Love uses social media to share short films of miniature cotton kitchens. Alexis Sugden embroiders her adorable characters frame by frame, as well as working as an animator for major TV series like Disney’s Monsters at Work. These women deserve the opportunities to show their work to the world that men have been afforded since the dawn of the art form.

Published 15 Jun 2023

Domee Shi’s feature debut about a teenage girl with an unusual power is Pixar’s best film in years.

His work on Who Framed Roger Rabbit earned him fans around the world, but it’s his generosity and humour I’ll remember most fondly.

From his studio in Dublin, the American animator rivalled Disney during the 1980s and early ’90s.