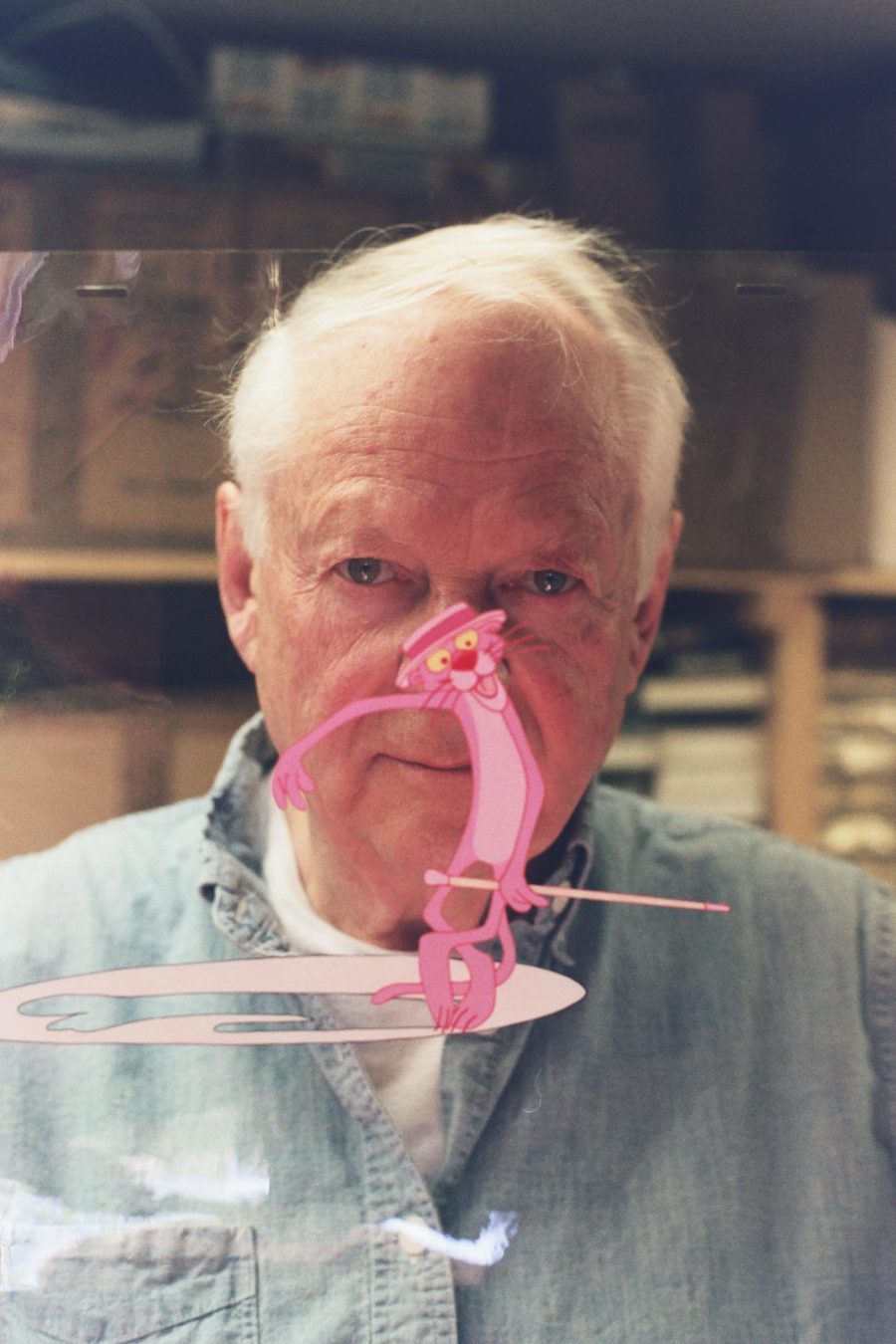

My father is best known as the master animator who created Who Framed Roger Rabbit, animated the title sequences for the Pink Panther films and grafted for 35 years on his unfinished epic The Thief and the Cobbler, setting a world record for the longest film ever in production. He won over 250 international awards including three Oscars and three BAFTAs. Dick’s studio worked on over 2,500 commercials including everything from babies’ nappies to Mini Cheddars to Shell Oil.

Dick was a director, producer, writer, author, teacher and voice actor (most famously for Droopy in Roger Rabbit; he actually did the voice the day he died). He was all of those things. He was also one of the most generous, funny, modest, anarchic and direct people you could ever hope to meet.

He was fascinated by life, especially by motion. One of his most important skills was his ability to learn and improve his craft. When his mentor and colleague Ken Harris first saw the animated sequences of The Charge of the Light Brigade in 1968 he said to Dick, “All that cross hatching. All that work. But it don’t move too good”.

At 35 years old, already the head of a successful animation studio, Dick realised he would literally have to go back to the drawing board and develop his animation skills. Over decades of study, Dick and his wife and collaborator Imogen Sutton distilled his knowledge into their Animation Masterclasses, and further refined it in his book The Animator’s Survival Kit, known as the animation bible.

Dick was in his eighties when he felt he had finally mastered the medium. He had achieved his life goal, “to be able to animate anything I can think of, and make it convincing”. He believed that the 2015 Oscar and BAFTA-nominated short Prologue was his best work. The film was to be the first in a series of shorts inspired by Aristophanes’ play ‘Lysistrata’. Dick first had the idea when he was 15. He was working on the second instalment of the series up until the day of his death. Ever the actor, he personally recorded the outlandish female voice for the rotund, sexually overt, comic foil of Lysistrata. His joke title of the project was Will I Live to Finish This?

Dick was a natural actor, performing through his drawings, and would tell hilarious, perfectly-timed anecdotes about everything from his time in Hollywood, meeting stars like Tom Jones, Stephen Sondheim and inadvertently insulting the divorcee of Julie Andrews, to growing up in suburban Toronto, wading through giant mounds of midwinter snow to get to the grocery store to eat ice cream.

He was incredibly giving and interested in everyone he met, from the top to the bottom of society. One of the reasons why his work is so funny and so beautiful is because he was aiming to portray real life. He would ask anyone’s opinion of what he was working on, including the mailman.

His other life-long passion was jazz, particularly Dixieland. Dick was a celebrated cornet and flugelhorn player, leading jazz bands in London (including Dix Six). He also composed several Dixieland numbers.

Although Dick called himself a ‘pencil man’ he loved the different genres of animation, and encouraged animators to use every tool they could grasp, whether CGI, stop motion, crayon or even embroidery to push the medium forward. He taught the principles of animation so that students could take this knowledge and utilise it in their own way.

He was fascinated by the medium of film, worshipping filmmakers like Alexander Mackendrick and Akira Kurosawa. In fact, one of the last films we watched together as a family was Yojimbo. The last book Dick read was on Kurosawa’s life and work.

Dick’s brother Tony describes him as an “Energizer bunny”. Tony is right. At the age of 86, he was still swimming 32 lengths, five days a week. His life-long teaching career started age 14 at the Toronto YMCA, where he taught swimming. He was helping me improve my swimming technique at age 85.

Dick was highly disciplined and focused, working seven hours a day, seven days a week. When he woke up in the morning, he couldn’t wait to get to his desk. When he went to bed at night he would still be talking about animation. He worked up to six o’clock in the evening on the day he died.

Through his innovations on the screen, as well as in animation masterclasses, how-to books, DVDs and an iPad app, Dick leaves a treasure trove of tools for animators, students and lovers of the craft. He only ever wanted to improve his work, and wanted others to push forward as well. As Dick would say, “Get on with your own knitting.”

He was the king of animation. And he still is.

Published 23 Aug 2019

From his studio in Dublin, the American animator rivalled Disney during the 1980s and early ’90s.

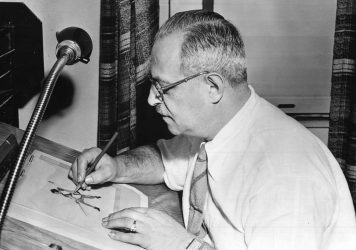

Max Fleischer, creator of Betty Boop and the rotoscope, was one of the great cartoonists of the 20th century.

By Jesc Bunyard

Moana directors Ron Clements and John Musker reflect on how Robin Williams broke the mould in Aladdin.