By all accounts, Walt Disney is the reigning king of American animation. But for a while, he shared the title with Max Fleischer, a Polish immigrant and one of the great cartoonists of the 20th century, whose gritty, subversive work was a significant challenger to Walt’s wholesome creations.

Originally from Krakow, Fleischer moved to New York City as a child in 1887. He lived through the Jazz Age and witnessed the Roaring Twenties crash into the Great Depression. He also grew up in America’s invention era, and was among the first to see Thomas Edison’s projection machine cast a flickering image onto the side of the New York Herald building on 34th street.

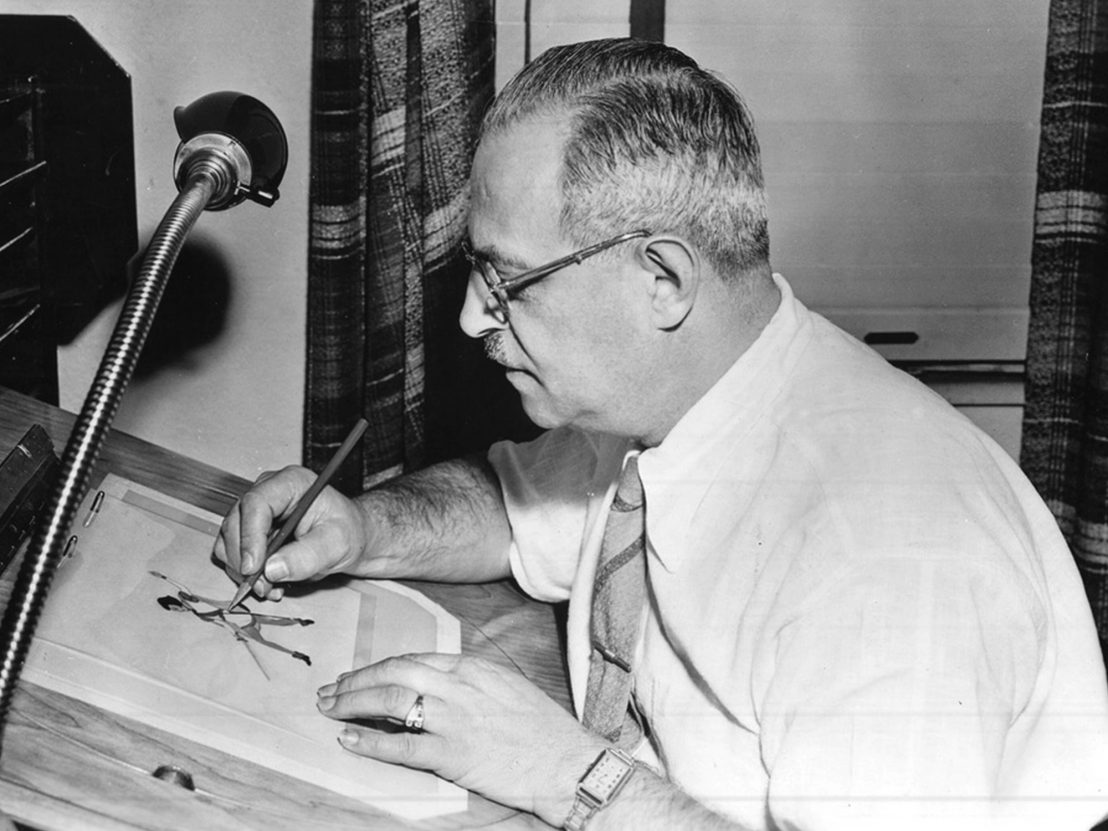

The story goes that after seeing Winsor McCay’s 1914 animation Gertie the Dinosaur, Fleischer saw the potential of moving cartoons and began his own experiments. By 1915, he and his brother Dave had invented the rotoscope, a process that allowed the artist to trace the filmed movement of a person frame by frame, resulting in a smoother, more lifelike animation. The Fleischer brothers’ innovative technique is still used to this day, recently forming the basis of Loving Vincent and Tehran Taboo.

After various animation jobs, the Fleischers set up Inkwell Studios in 1921, which later became Fleischer Studios, where they began producing cartoons on behalf of Paramount. They enjoyed massive popularity during the silent era thanks to their ‘Song Car-Tunes’. A precursor to karaoke, these interactive cartoons invited audiences to sing along by following a little ball that bounced along the top of the words on-screen. One such short, 1926’s My Old Kentucky Home, was actually the first ever cartoon to synchronise voice recording with animation, preceding Disney’s Steamboat Willie by two years. Not that Disney admitted this – he claimed the achievement as his own and attempted to have references to these early Fleischer’s early works swept under the rug.

Voice cartoons allowed Fleischer’s edgy New York team to flourish. Their dark, sinister animations often featured characters based on the downtown wise guys Max and his brother encountered in East Brooklyn growing up, as well as music performances from popular artists of the day. In the 1933 animation St James’ Infirmary Blues, Koko The Clown performs a jazzy dance (rotoscoped from the legs of Cab Calloway) through a dark cave, its blackened walls adorned with inked skeletons shooting dice. And in the 1930 cartoon Swing You Sinners, ghouls armed with razors and nooses chase Bimbo – a chubby cartoon dog – through a haunted cemetery after he steals a chicken. The world melts and mutates around him until eventually, he’s devoured by a giant, laughing skull.

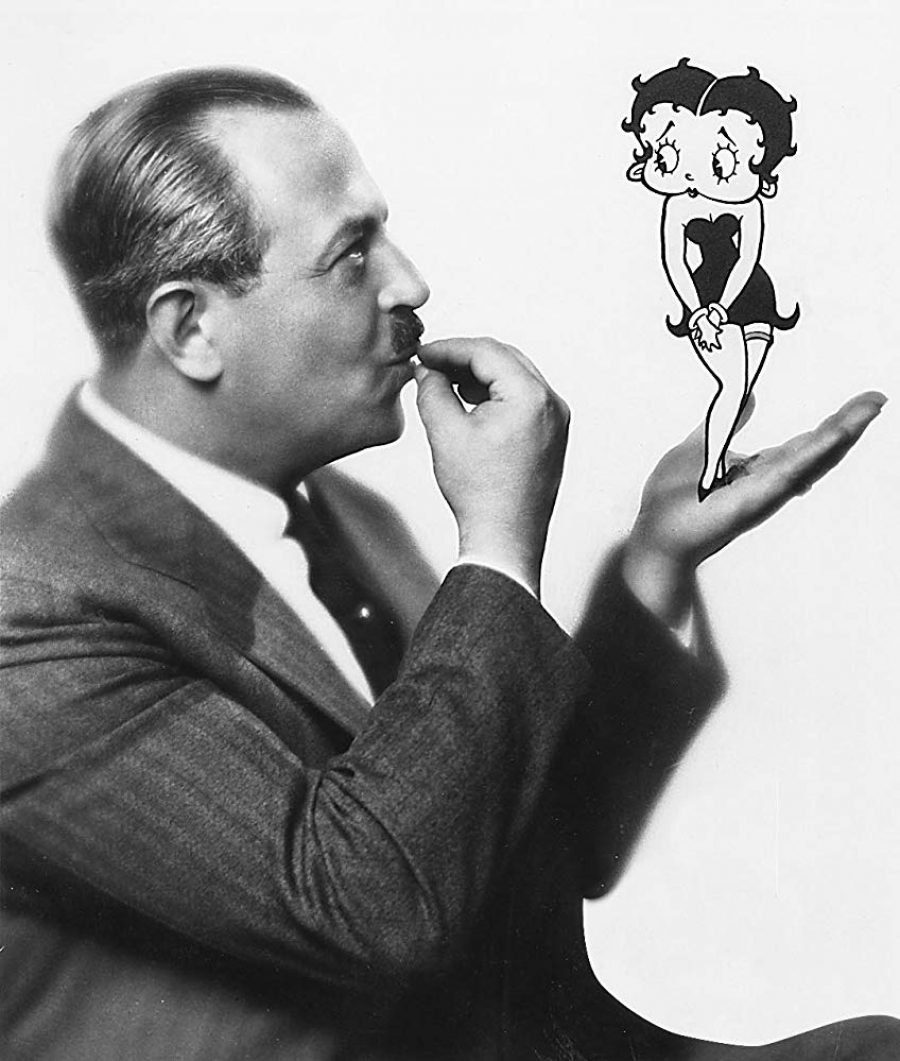

Betty Boop, a doe-eyed flapper girl, would go on to become one of the studio’s most enduring creations. Originally the love interest of Bimbo, she was an anthropomorphic French poodle with dog ears before she was made into a human girl based on the singer Helen Kane. Her floppy ears were transformed into hoop earrings, and she lost her canine button nose. Kane herself spotted the similarity and tried to sue Paramount and Fleischer Studios for stealing her likeness – though the case folded when lawyers rightly pointed out she had, in turn, appropriated the style and voice of Gertrude Saunders (stage name Baby Esther), an African-American singer who regularly performed at The Cotton Club in Harlem.

Betty remained a popular sex symbol right up until the Production Code of 1934, which imposed restrictions on adult content and cramped the studio’s style. Her hemline was lowered to puritanical levels and her naughtiness was reigned in, massively reducing her appeal. Without her overt raunchiness, she had no purpose. Gone were the days where she’d whack a lecherous old man in the face and seduce Bimbo into joining a cult. The studio was losing its bite, while an ambitious Walt Disney was waiting in the wings, soon to steal the spotlight.

Two opposing animation styles were developing at opposite ends of the country. Fleischer’s gritty streets of New York verses Disney’s sunbaked Midwest. The former’s philosophy was ‘if it can be done in real life, then it isn’t animation’, and his NYC studio continued producing wild characters who melted and mutated, in a grimy, ripped-up urban settings. But Walt ultimately had a better grasp of what sold. He steered clear of sex, jazz and psychedelic surrealism, instead training his artists to create lush, bright cartoons full of cute characters who behaved more realistically.

Disney took bigger risks while diversifying his output, shifting his focus to feature-length animations, TV cartoons, and eventually, theme parks. He also realised early on that the entire movie industry was moving to Hollywood on the West Coast, and set up a studio in sunny California. East Coast studios were closing up, but Max refused to budge.

Storm clouds were gathering over Fleischer Studios. The brothers had fallen out due to Dave’s adulterous affair with his secretary. Meanwhile, Paramount’s unrealistic production demands put a strain on the team and finally, in May 1937, the workers went on a bitter five-month strike. Following this, the brothers decided to pack up and move to Florida, but away from the vibrancy of New York, the uninspired animators lost their edge.

To add salt to the wound, Paramount refused to invest in a three-colour Technicolor processes, allowing Walt to steam ahead with beautifully colourful creations, including the feature-length Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which went on to win an honorary Oscar for Best Musical Score at the 11th Academy Awards. The world of animation had changed forever, and the Fleischers were now trailing behind.

Max had been petitioning Paramount about creating a feature-length animation for years, but it wasn’t until the success of Snow White that execs finally realised its value. So in 1938, when the Fleischers were in the middle of building their Miami studio, they made Gulliver’s Travels, followed by Mr Bug Goes to Town – both of which were commercial flops. Max and Dave resigned and Paramount removed the Fleischer name. Max eventually won a lawsuit to reinstate it in 1955, but by then, his career was over. Disney came out on top and the Fleischer name slid into obscurity.

Max Fleischer’s story is one of an artist struggling to keep up with a changing world, but also one of fearless creativity – his inventions and triumphs shaped animation as we know it today. And despite being eclipsed by Disney, Max held no hard feelings. When Walt asked Max’s son Richard to direct 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Max happily gave him his blessings. Although rumour has it, every time Richard mentioned Walt’s name, his father would reply “that son of a bitch.”

Published 10 Nov 2018

By Matt Packer

Legendary animator Floyd Norman tells the inside story of how a Disney classic was made.

By James Clarke

In 1946 the moustachioed maestros embarked on the most ambitious project of their careers.

From his studio in Dublin, the American animator rivalled Disney during the 1980s and early ’90s.