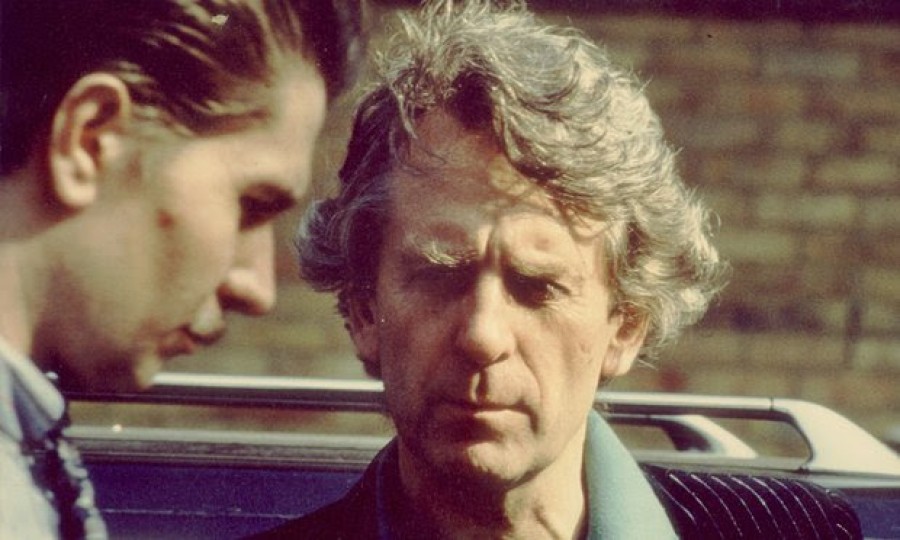

Alan Clarke was one of Britain’s most radical, political and groundbreaking filmmakers whose work often focused on society’s underdogs and fringe groups. His gritty social realist style has influenced everyone from Paul Greengrass to Clio Barnard, Shane Meadows and Andrea Arnold.

One of Clarke’s most acclaimed and controversial films, The Firm shocked television audiences in 1989 with its unflinching depiction of football hooliganism. In one of his earliest starring roles, Gary Oldman plays Bex Bissell, the ‘top boy’ in a London firm. A symbol of Thatcher’s Britain and a product of his time, Bex is an estate agent addicted to the buzz of being a football hooligan. The violent subculture is ingrained into his lifestyle. Clarke once stated that the character was a response to how he saw the Tory government’s complete misunderstanding of the neoliberal society they had created.

Throughout the 1980s English hooliganism caused a stir all over Europe, arguably peaking at the 1990 World Cup in Italy where England were forced to play all their group stage matches away from the mainland in the Sardinian capital of Cagliari, such was the fans’ reputation. The Firm may not have reduced weekend violence or altered the image of English football fans, but crucially it brought viewers up close and personal with firm members.

In stark contrast to the slicker, glorifying hooligan films that followed it, The Firm champions a social realist viewing experienced enhanced by its low-budget aesthetic. It delivers a strong message while revealing something about the evolution of Hooliganism, addressing how the subculture evolved from attracting track-suited ruffians to lower-middle class men by the late ’80s. No longer was it about working class skinheads, who originally adopted the movement in protest against the government.

As seen in The Firm, this new breed of weekend offender typically worked skilled jobs and wore a sharp-suited look. In a TV interview within the film, the then modern day hooligan is said to desire some form of validity in their life. Clarke’s characters attempt to prove that they are not cut from the same cloth as the working class ‘scum’ that previously represented hooligan culture. But really, despite appearance, these hooligans were no better than those who had come before them, although Clarke’s characters do appear more integrated into society.

Clarke’s prerogative wasn’t to make a shocking exposé, but to show how these types of firms operated “in a ritualistic kind of way.” Shortly it becomes apparent that the violence doesn’t actually revolve around football, but has everything to do with the hooligans’ machismo behaviour. Clarke himself was a avid Everton FC supporter and stressed that the main point of the film is that the problem is not football, but the people who use the sport as an excuse to exercise their hooliganism. The Firm stresses this notion throughout to the extent that an extra directly addresses the television cameras, stating that the firm would be causing riots even if they were associated with snooker, tennis or darts. To this day, there’s never been a football hooligan film quite like it.

Published 13 Aug 2016

BFI Flare’s opening film, The Pass, is about a prominent footballer who represses his sexuality. We explore why this is still happening for real.

A 30th anniversary re-release for Alex Cox’s tragic tale of punk royalty lost to the needle.

By Greg Evans

Twenty years ago Sean Bean drama When Saturday Comes cast the beautiful game in a darker, more honest light.