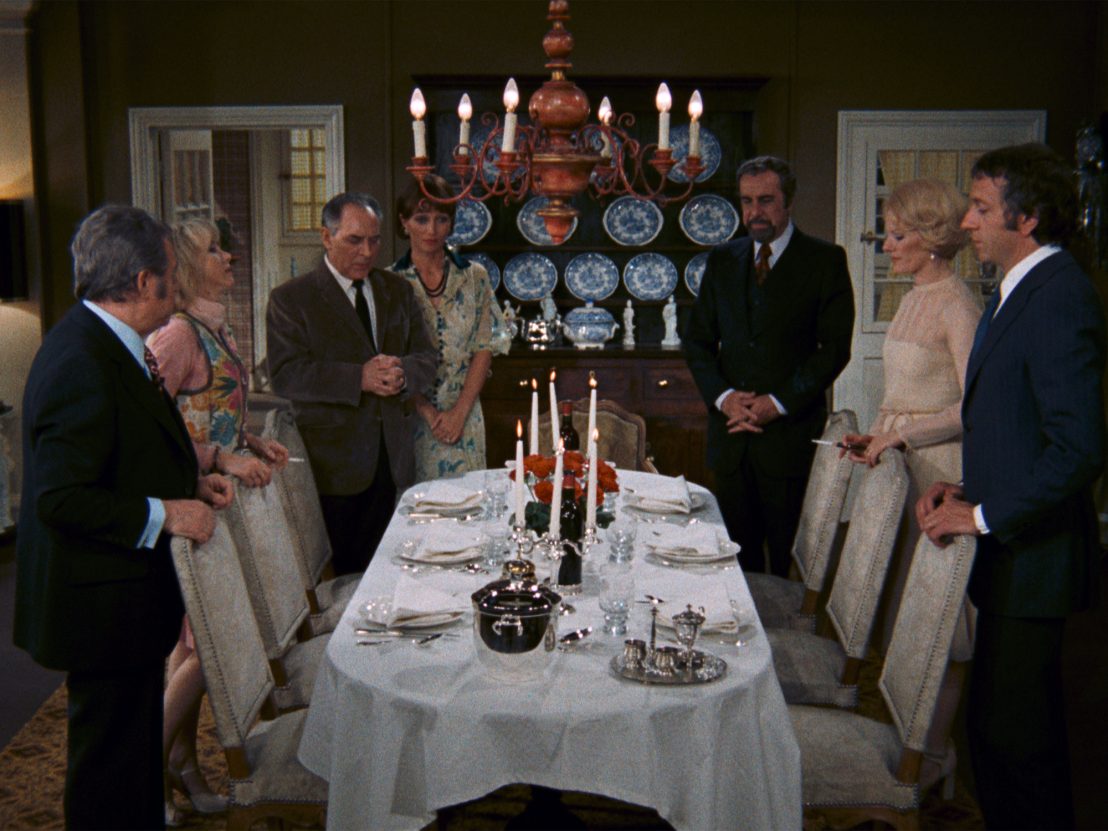

Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie opens with the ambassador Rafael Acosta (Fernando Rey), his colleague François Thévenot (Paul Frankeur), François’ wife Simone (Delphine Seyrig) and younger sister Florence (Bulle Ogier) being driven one night by Rafael’s chauffeur to an opulent house in the country. There they are expecting to dine with another colleague Henri Sénéchal (Jean-Pierre Cassel, father of Vincent) and his wife Alice (Stéphane Audran) – only they have come on the wrong night.

For, owing to a mix-up, they are expected the following evening, there is no dinner ready for them, and their host Henri is not even at home. So the four head off with Alice (still in her nightgown) to a nearby bistro, only to find that the owner has recently died and his body is still laid out in an adjoining room where the staff are mourning him. The immediacy of this memento mori puts the five off their food, and so they leave once again without a meal.

This absurdist opening sequence lays out several key themes of The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie. For the casual rudeness of our five would-be diners to the bistro’s staff reflects a broader disdain for the working classes, as these members of the affluent haute bourgeoisie proudly display their sense of entitlement. And Simone’s horror and revulsion, when confronted with the bistro owner’s corpse, points to the way that the contagion – indeed the very inevitability – of death itself threatens this party’s self-image of a godlike immortality which, in their mind, separates them from the normal rules that govern mere mortals.

There might be a ‘discreet charm’ to the way that these six – especially the men – brush themselves off with real sangfroid whenever their (dinner) plans go awry, but they are imperious, arrogant, awful people who imagine themselves naturally better than all who serve under them, and who repeatedly flout morality and the law even as they snobbishly insist upon their own superior breeding, refinement and manners.

Meanwhile the film’s episodic narrative will be structured around numerous attempts by these characters, to enjoy a lunch, afternoon tea or dinner with each other (in different constellations and settings), only for their meals to be interrupted, disrupted or generally frustrated for one reason or another. This prandial – one might call it consumerist – obsession makes the film form a bizarre counterpart (in diptych) with Buñuel’s earlier The Exterminating Angel (1962), whose aristocrats find themselves unable to leave the dinner table after their meal.

Rafael might revel in his status as the ambassador of the Republic of Miranda, and the title of His Excellency which that status confers upon him, but really Miranda is an impoverished, politically repressive tinpot dictatorship, a refuge for Nazi exiles, and a hotbed of criminal activities. Indeed Rafael’s wealth comes from similar corruption: the cocaine that he smuggles into France via his diplomatic bag – and that François and Henri then sell on for profit.

These men’s indignation when they discover that soldiers temporarily billeted at Henri’s house smoke marijuana is a sign of their immense hypocrisy (“I loathe drug addicts”, declares François, with Rafael asserting his agreement). Rafael is not just playing the system, but cheating his own friend, as he regularly enjoys covert assignations with François’ wife (although the sex, like the dinners, gets interrupted). And while Rafael might present a front of charming grace to the female revolutionary (Maria Gabriella Maione) who comes armed to his door, he only lets her go so that his thuggish agents waiting outside can intercept and abduct her to face unspeakable horrors at home. For all his suits, social fluency and ‘chivalry’, Rafael is far from civilised.

While others in the film have dreams (vividly realised, as they are narrated, on screen) about the ghosts of the past returning for revenge or redemption, the dreams of our three bourgeois antiheroes expose their deep-seated anxieties and their guilty consciences. For Henri dreams of being at a dinner party performed live for a theatre audience, and forgetting his lines on stage. François dreams that Rafael, having been hassled by the guests at a party about the questionable conduct of Miranda, shoots the host dead to restore his own honour. And Rafael himself dreams that a dinner at Henri’s is interrupted by gun-toting revolutionaries come to kill everybody at the table.

In fact the six friends will all be arrested during a lunch, and the arresting commissaire (François Maistre) will then dream that a revenant policeman releases them. In actuality, though, it is the men’s connections with (by implication, equally corrupt) political élites that will see them released from their cells without charge, and free to carry on breaking the law with impunity. The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie is full of surreal sequences revealing its characters’ unconsciouses – but it also offers up a far more cynical, all too recognisable reality.

About halfway through The Discreet Charm Of The Bourgeoisie, a downwardly mobile Bishop turned part-time gardener (Julien Bertheau) chats with Rafael and betrays, with repeated gaucheness, his ignorance of Miranda. First he refers to Bogota as its capital, confusing Miranda with Colombia; then he praises “the Andes cordillera, the pampas”, as though it were Argentina; and finally he mentions its “ancient pyramids”, which, as Rafael points out, are actually found in Mexico and Guatemala. The truth is that Miranda is a fiction, invented by Buñuel for this film – although it is also clearly a composite of all these places and all their problems (, the vast social divisions, the drug production, the military dictatorships, the guerrilla counterforces, etc.).

Buñuel’s six bourgeois characters are much the same as the distant country that unites their fortunes. For while they are not real people, everything about them is familiar from our ruling classes and moneyed élites, who work only to benefit themselves, who treat the rest of us with contempt, and who, for all the privileges and perquisites that they enjoy, are always hungry for more. Buñuel has served up something deliciously funny, but bitter in its aftertaste.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie is released on 4K UHD, Blu-ray and DVD, 20 June, 2022, by StudioCanal.

Little White Lies is committed to championing great movies and the talented people who make them.

Published 20 Jun 2022

By Anton Bitel

The director’s short experimental feature, Lux Æterna, plays like a panic attack before reaching a rapturous crescendo.

By Anton Bitel

The likes of A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream owe something to Robert Deubel’s co-ed carve up Girls Nite Out.

By Anton Bitel

Fredric Hobbs' surreal 1973 film sees a giant mutant sheep terrorise the residents of a sleepy town in rural Nevada.