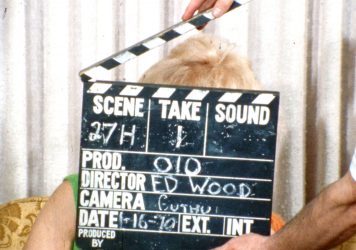

Edward D. Wood Jr (1924-1978) has achieved the kind of immortality that most filmmakers will privately dream of, but very few can ever expect to attain. He’s a cinematic yardstick, a reference point that is near universal within film circles. But at what cost? Ever since the publication of The Golden Turkey Awards in 1980, “Ed Wood” has been synonymous with “worst”. This seminal compendium of junk cinema all but cemented Wood’s posthumous legacy when it awarded him the twin honours of Worst Movie of All Time (for his 1959 science fiction-horror film Plan 9 from Outer Space) and Worst Director. But is he really? No, of course not.

Wood may have made films quickly and cheaply on the very lowest rung of 1950s Hollywood film production, but his films harbour no malicious intent (if there were to be a plausible metric with which we could establish an all-time worst filmmaker, surely it would be moral rather than aesthetic). But one needn’t damn Wood with such faint praise, nor defer to the subjective nature of art appreciation in order to mount his defence. His films possess demonstrably good qualities. They’re snappily paced, imaginative, thematically ambitious, and filled with potent pop images. While Plan 9 from Outer Space remains his most remembered (if not best remembered) film, the Wood production that perhaps makes the best case for his reappraisal is his 1953 exploitation quickie Glen or Glenda, a landmark film for on-screen gender nonconformity.

Originally mooted by grindhouse producer George Weiss as a cash-in on the media circus surrounding Christine Jorgensen’s highly publicised “sex change”, Wood re-conceived the project as a semi-autobiographical film incorporating his own experiences as a crossdresser. Outwardly, Glen (portrayed by Wood himself) is the picture of clean-cut, all-American masculinity. He’s about to marry his beautiful and loving fiancée Barbara (Dolores Fuller, Wood’s real-life girlfriend), but there’s another woman in Glen’s life – his “other self”, Glenda. He’s been happily cross-dressing in private for years but now, with the wedding looming, the presence of Glenda has become a real threat to Glen’s future happiness with Barbara. Dare he reveal his shocking secret to her? Could love conquer all?

Glen or Glenda is deeply unconventional for a commercial release of its day, both in terms of its subject matter and its form. Across a brisk 61 minutes it straddles a multitude of genres and styles: melodrama, horror, quasi-documentary, rambling lecture, and free-associative film poem. Though he occupies a slim portion of the runtime, faded horror star (and close personal friend of Wood) Bela Lugosi gets top billing.

His role, that of an omniscient god-like scientist, serves as one of the film’s two narrators, occupying two entirely distinct framing devices. Surrounded by test tubes and leatherbound volumes, Lugosi muses on the action in a series of labyrinthine Twilight Zone-ish monologues, cryptically opining on “man’s constant probing of things unknown” and so on. The second narrator is Dr Arden (Timothy Farrell), a psychiatrist being consulted by a bewildered inspector (Lyle Talbot) after the suicide of a transvestite.

Both of the parallel narrations display Wood’s characteristic penchant for purple prose, but they are clearly intended to serve two separate functions. Farrell’s voiceover is dry and matter of fact, its faux-academic verbiage as unconvincing as its supposedly scientific insights (at one point he claims that male baldness is caused by tight hats). This narration explicitly medicalises gender non-conformity, ostensibly justifying the film’s existence as an educational object and therefore helping it to evade censorship (a common tactic in early exploitation cinema). It is perhaps left for Lugosi, then, to articulate Wood’s more complex and personal feelings on the subject. His witchy passages evoke a sense of cosmic mystery, and there’s a sense that Wood may be using him to describe existential dread brought on by living a marginalised life.

While Lugosi may or may not serve as Wood’s mouthpiece in Glen or Glenda, both Glen and Glenda are certainly his on-screen avatars. There are so many tender details that betray lived experience – Barbara noticing that Glen is growing out his fingernails and teasingly suggesting they paint them “just for the fun of it.” The revelation that Glen first crossdressed for a Halloween party, which remains a common formative experience for trans and gender non-conforming people. The impossibly vulnerable image of Glen as Glenda staring longingly at the mannequins in a department store window – a plastic standard of feminine beauty she feels sure she’ll never meet.

But the film really takes flight when these down-to-earth moments collide with Wood’s expressionist tendencies. At one point, Glen is out shopping for a negligee – he takes a moment or two too long feeling the fabric in front of a quizzical shop assistant when, suddenly, Wood cuts to stock footage of lightning with an accompanying thundercrack. How might we interpret this strange choice? Could it stand for sexual arousal? God’s judgement? Glen’s fear?

The received wisdom is that Glen or Glenda is a badly made film, and that its ambiguities are the product of incompetence. But Wood was endeavouring to describe emotions and experiences for which there was little-to-no available language, let alone cinematic language. His attempts to fill this linguistic and aesthetic deficit are scattershot, yes, but the tension between a palpable desire to bare his soul and his inability to express himself clearly is ultimately what makes the film so compelling.

As such, Glen or Glenda’s most deeply confessional feeling passage is also its most experimental: an elongated, hellacious nightmare sequence. It’s here that any tidy division between Glen and Glenda evaporates as we watch Wood move fluidly between personas across cuts and dissolves. We see Barbara trapped beneath a tree – Glenda cannot lift it, Glen can. Lugosi grimly intones that there is a “big green dragon” that “eats little boys”, and we hear the mocking voice of a little girl, bragging that she is “sugar, spice and everything nice.” The Devil himself commands a mob of ghostly bigots to back Glen into a corner, but Wood re-emerges defiantly as Glenda, leaving the throng seemingly blinded by her sheer effervescence. This sequence is a filmmaker’s id unmoored. It’s corny, disturbing, and heartbreakingly beautiful.

In what feels distinctly like an ending, Glen finally tells Barbara his secret. While conceding that she “may not fully understand” the situation, she wants to do right by her beloved. Then, in the film’s most enduring image, she first removes and then hands over the angora sweater Glen had long coveted in secret. It’s a gracefully composed melodramatic tableau, one worthy of Douglas Sirk. Unfortunately, while Wood’s imagery speaks louder than his clunky dialogue and duelling narrations, neither Glen nor Glenda are allowed the last word. Dr Arden (who is revealed to have been “treating” Glen after his coming out to Barbara) bluntly explains that Glenda was simply the manifestation of a lack of motherlove.

He informs Glen that he must “transfer” Glenda to Barbara, and then all will be right. Wood cannot outrun the censors indefinitely: the deviant must either be punished or reformed. Of the available options, it’s no wonder that he chose the latter. But this self-evident compromise does not diminish the scale of Wood’s achievement. Glen or Glenda is a miracle, one ready and waiting for rediscovery.

Published 14 Apr 2023

By Will Sloan

The cult director’s long-lost sexploitation comedy is finally being released on home video.

Is the default assumption of the giant lizard’s maleness just plain sexism?

From Alfred Hitchcock to Fritz Lang, the process of creating women has long been an obsession of cinema’s greatest male creators.