In November 2018, a long-lost late work by a legendary auteur will finally emerge. The filmmaker was a maverick who operated largely outside the system, piecing together deeply personal films despite his own financial insolvency. In the film in question, he reckons with the new realities of Hollywood while working in a sharply different style. For fans and film historians alike, this unseen work has felt like a missing puzzle piece. If only we could just see it – then, perhaps, an enigmatic career might finally click into focus.

No, I’m not talking about Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind but Take It Out in Trade, a recently exhumed 1970 sexploitation comedy by the so-called “Worst Director of All Time”, Edward D Wood, Jr. Long assumed to have been consigned to the landfills that have claimed so many independent productions, the film will finally receive a home video release on 13 November courtesy of the American Genre Film Archive and Something Weird Video. A 2K scan of the only surviving 16mm print will also screen in repertory cinemas. Not a bad fate for a film whose world premiere was reportedly at a topless bar in Glendale, California.

Take It Out in Trade was Ed Wood’s first directorial effort in a decade, long after the films that form the bedrock of his cult reputation (notably 1953’s Glen or Glenda, 1955’s Bride of the Monster and 1959’s Plan 9 from Outer Space). By this point, he was a serious alcoholic who made his living writing sleazy paperbacks (sample titles: ‘Death of a Transvestite’, ‘Suburbia Confidential’, ‘The Sexecutives’). Within a year, he would be making hardcore pornography. Though it emerged during Wood’s decline, Take It Out in Trade is lively and upbeat, and as imaginative as anything he made – enough so that it can’t quite be dismissed as ‘so bad it’s good’. Just as the raw, ramshackle The Other Side of the Wind is the stylistic inverse of Citizen Kane, there’s plenty in Wood’s film to challenge anyone who thinks they know exactly what kind of bad filmmaker he was.

For starters, it’s funny – often intentionally so. Though made on the cusp of the hardcore revolution, the film is in the spirit of the early “nudie cuties” of Russ Meyer or Herschell Gordon Lewis, in which goofy guys made ‘gee whiz!’ facial expressions at the sight of bare-breasted women. The goofy guy here is Mac McGregor, (Michael Donovan O’Donnell), a private eye who specialises in sex, and has more than a scholarly interest in the subject (“Sex. That’s where I come in. Dead or alive, sex is always in need of my services. A service to which I sincerely apply myself wholeheartedly – sometimes even in the daylight hours!”).

The plot begins when McGregor is hired by a wealthy couple to find their missing daughter, Shirley (Donna Stanley), who has run away to work at a brothel. With an expense account at his disposal, McGregor embarks on a needlessly complicated globetrotting adventure, hanging out at whore houses around the world before grudgingly returning to the case. Wood has fun with his low budget, frequently showing footage of a plane leaving LAX before cutting to a character standing in front of, say, a Rome travel poster.

Secondly, a half-joking question: has any other great black-and-white stylist so lustily embraced the possibilities of colour? Like Wood’s subsequent hardcore features Necromania: A Tale of Weird Love! and The Young Marrieds, Take It Out in Trade, is a retina-blast of red shag carpeting, gold curtains, baby-blue wallpaper and bright green dresses. Stylistically, it violates a few dozen basic rules of film grammar (the editing in back-and-forth dialogue scenes is particularly atrocious), but Wood also breaks from the static compositions of Plan 9 from Outer Space, letting his camera roam freely around the beds and bodies of his characters. It’s a chaotic visual experience, but it feels alive in a way that a lot of sexploitation films don’t.

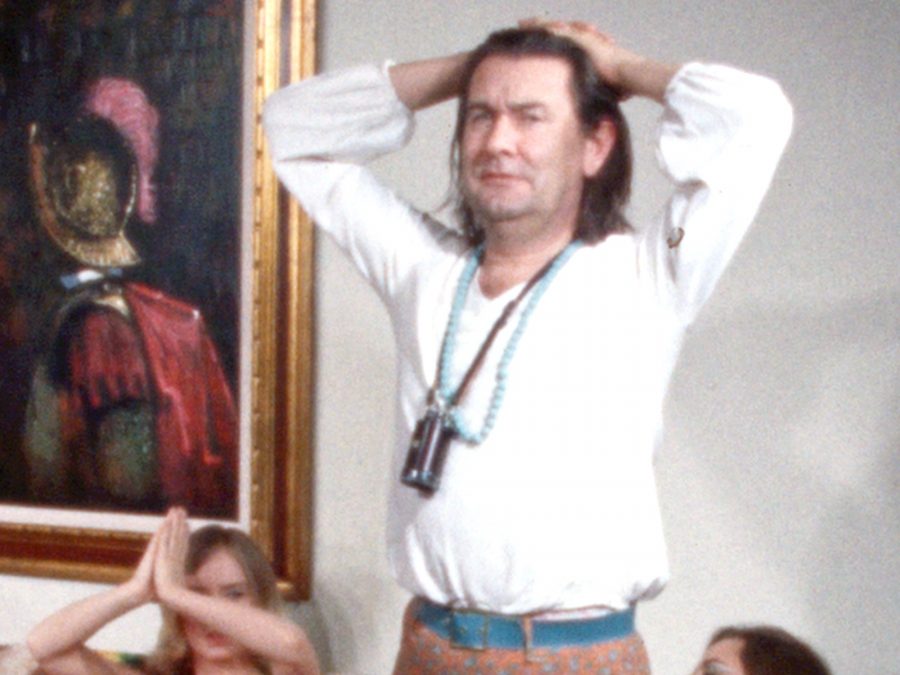

The film’s biggest surprise, though, is that it’s actually quite progressive. For a sexploitation film from 1970, at least. It’s still a very male-gazey experience, and the many scenes of McGregor spying on naked women caused discomfort when the film screened at Fantastic Fest in 2017. But Wood is creative enough to play a few jokes on that gaze, as in the scene where McGregor watches a shapely woman putting on a negligee until she turns around to reveal her true identity. More to the point, Wood’s vision of Los Angeles is also dotted with characters from across the LGBTQ+ spectrum depicted nonchalantly, including a transgender couple and a drag queen played by Wood himself.

For Woodologists, this point is worth lingering on. Though he had a famous proclivity for cross-dressing, his oeuvre doesn’t follow any straightforward liberal agenda. Glen or Glenda has been rightly cited for its empathetic depiction of sexual diversity, but it also ends with Glen being “cured” of his cross-dressing compulsion through therapy, and the love of a good woman. The film’s B-story depicts the plight of Alan/Anne, whose sex-change is accepted because she will eventually conform to the gender binary (“Alan had all his life acted the part of a woman. Now he is that woman and must learn how it’s done. Anne must learn how do her own hair, how to make the correct styling for her facial contours…”).

Elsewhere in Wood’s work, the gender binary is a site of power and humiliation. In the ironic coda of The Young Marrieds, a male chauvinist who pressured his wife into group sex is forced into a same-sex encounter. In Love Feast, a Wood-scripted softcore romp, Wood’s lecherous photographer is forced to crawl around in a dog collar and frilly pink nightdress, licking the boots of the women who have turned the tables on him. Drag recurs in Wood’s pulp novels, which abound in erotically-charged scenes of men passing as women. In the context of Wood’s career, Take It Out in Trade is unique for presenting sexual diversity as simply no big deal. All of which is to say the film is not for those who just want to laugh at it, and appreciating it requires appreciating Wood as a weird guy with a weird perspective.

It also requires appreciating Wood’s Hollywood – a colourful, sometimes sordid tapestry where flower children, cross-dressers, junkies, madams and wealthy families all live within a few blocks of Detective Mac McGregor. As J Hoberman wrote in Film Comment in 1980, “Wood was a toadstool at the edge of Hollywood, nourished by the movie industry’s compost.” Beyond the cheap special effects, Plan 9 from Outer Space has a Boulevard of Broken Dreams resonance. In ‘Holly-Wood’, has-beens (Lyle Talbot, Tom Keene, the late Bela Lugosi) rub shoulders with LA novelty celebrities (Criswell, Vampira, John “Bunny” Breckinridge) and wannabes from Wood’s entourage. None of these people belong together, and yet here they are in front of a pitch-black backdrop in a tiny studio in an alley off Santa Monica Boulevard. Wood’s Hollywood is best summed up by a line from his 1959 film Night of the Ghouls: “This is the story of those in the twilight time – once human, now monsters, in a world between the living and the dead.”

Wood died in 1978, homeless at age 54, two years before being crowned “The World Director of All Time” in Harry and Michael Medved’s book ‘The Golden Turkey Awards’. Since his rediscovery, and especially since Tim Burton’s 1994 biopic Ed Wood, the excavation of “lost” Ed Wood films have become a cottage industry. In the ’80s, entrepreneur Wade Williams finally settled Wood’s unpaid lab bill for Night of the Ghouls. The ’90s saw the completion of Wood’s early short Crossroads of Laredo as well as a star-studded production of his last script, I Woke Up Early the Day I Died. His porn films Necromania and The Young Marrieds turned up in the 2000s, and the 2010s saw the resurrection of his TV pilot Final Curtain and the apocryphal Nympho Cycler. In 2016, the website cinefear.com even compiled two DVD collections of the short, hardcope porn loops he cranked out during the ’70s. For a certain niche audience, there is a bottomless appetite for everything this “bad” filmmaker had to say.

Take It Out in Trade has been the most elusive of Wood’s phantom texts. In the definitive biography ‘Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D Wood, Jr’, author Rudolph Grey reported locating a print, and wrote of its “para-psyechadelicism and surrealism,” but the film remained out of public view, and there was no guarantee the print had survived. In 1995, Something Weird Video released Take It Out in Trade: The Outtakes, a 69-minute compilation of silent bloopers and alternate takes. It’s a frustrating experience, packed with striking images but very tedious, and raising questions about just how all this stuff could fit together.

“It was very confusing and surreal, and I couldn’t stop thinking about it after I watched it,” says Joe Ziemba, director of the American Genre Film Archive (AGFA) and a lifelong Wood fan. “It’s like seeing something that you’re not supposed to see, and it’s a piece of something, yet it’s not a piece of something. It kinda gives you some insight into what the movie is, but, in a way, it’s also more exotic than the movie itself. You’re seeing all the in-between moments, and you’re seeing Ed Wood at the end in his amazing flower-print pants directing the movie. It’s really thrilling, and it’s also really boring, but I watched it at least two or three times in the last 20 years.”

In 2014, New York’s Anthology Film Archives unexpectedly screened an unrestored digital transfer of Take It Out in Trade as part of a Rudolph Grey-curated Wood retrospective, but this one-night event did not lead to a wider release. A turning point came in 2016, when Ziemba met with Grey and filmmaker Frank Henenlotter to record a commentary track for AGFA’s Blu-Ray release of The Violent Years. “At the end of that recording, Rudolph was packing up his stuff, and I was like, ‘Can you tell me about Take It Out in Trade? What do you know about it? Where is it?’ He immediately said, ‘How much can you pay for it?’”

The print, it turned out, was sitting in a closet in Los Angeles home of a producer’s son. Why did it take so long to get out? “The amount of money they wanted for it was, I think, probably a deterrent for people back in the day,” says Ziemba. “And if Mike Vraney and Lisa Petrucci [of Something Weird Video] weren’t going to put it out, who else was going to come to the rescue? There’s no one else who really knew the importance of the movie and would handle it the right way.”

The price was within AGFA’s budget, and a deal was quickly made. “We didn’t watch it before we scanned it, and the print was in really beautiful shape because it had never been seen,” says Ziemba. “I was really relieved, because a lot of the later Ed Wood stuff, especially the adult film work… y’know, it’s not for humans. It’s really hard to watch. I mean, Necromania has a little bit of plot in it, but for the most part, those movies are more of a fascinating time capsule of Ed’s work rather than a movie movie. With this, I was relieved, because this is an actual movie that feels like Ed Wood. It has his stamp on it. You can kinda feel like he has complete control on it, and he’s having fun.”

From a marketing standpoint, AGFA’s biggest challenge is repositioning Wood from the “Worst Director of All Time” to an outsider artist. “We are in a constant battle against ‘so bad it’s good’,” says Ziemba. “That’s just something that we can’t stand and want to wage war against. People that have that attitude going into movies are like bullies on a playground. We genuinely appreciate what he was doing – not just for his actual movies, but for who he was as a person. He’s a real hero for how bold he was, and the lifestyle that he had. He was just him, all the time.”

It’s a neat irony that Wood and Welles, two filmmakers on opposite ends of the auteurist canon, both have posthumous releases this year. But as their fictional meeting in Tim Burton’s biopic made clear, they were united by an indomitable creative spirit. Reading ‘Nightmare of Ecstasy’, it’s hard not to feel a little moved by the section about Take It Out in Trade. “Everyone in ‘Nightmare of Ecstasy’ talks about his unstoppable optimism,” says Ziemba. “Even when he was an alcoholic, he was always moving forward, always producing, always getting things out there. That feeling is in every frame of Take It Out in Trade. There’s an energy and optimism that’s there, and you can tell it’s his.”

Elsewhere in the book, actor Nona Carver recalls, “Ed went out to some clubs and he met some guy who wanted to get hold of pornographic pictures. Ed says, well, instead of going out spending money on these things I can make you a picture.” And Kathy Wood remembers her late husband editing the film while the bank was foreclosing on their house: “It was a cute little film which he cut and edited in his den on a moviola. It kept me up all night, practically. He wasn’t really making any money out of it, and he never did.” Wood may have been a con artist, but he wasn’t in it for the money.

Published 4 Nov 2018

By Matt Thrift

The legendary British director of Deliverance, Excalibur and Zardoz looks back over his extraordinary career.

By Emma Fraser

For a brief period during the 1930s, this unlikely idol became part of Hollywood’s glamorous elite.

By David Hayles

From Charles Bronson to Chuck Norris, David Hayles offers an indispensable guide to the cult production company.