As bare opening credits appear on screen at the beginning of Marco Ferreri’s The Ape Woman, they are accompanied by the sound of a band playing jaunty circus music. This is indeed to be a carnivalesque piece where all the world is a circus. Even the Neapolitan nunnery in which its first scene takes place is circus-like. As a seated assembly of mendicants listens to a visiting priest making an evangelical speech, and watches slides of missionary work in Africa, they jeer loudly at the ‘scary’ native women while leering at their nudity (“Being a missionary ain’t bad!”, one comments).

This sequence introduces the film’s key theme of exploitation. The old beggars endure the pictures and sermon as the price of the ‘free’ lunch being prepared for them by the nuns, while perceiving only low sensationalism in slides intended to educate and elevate them. Meanwhile, both the priest and the audience seem to share a basically racist view of Africa as a place of primitive lust and terror. The last, overtly fake-looking slide seen shows a topless black woman holding up in triumph the severed head of a missionary – an image apparently designed to illustrate the saintly self-sacrifice of priests abroad, but which also resembles something straight out of an exploitation film.

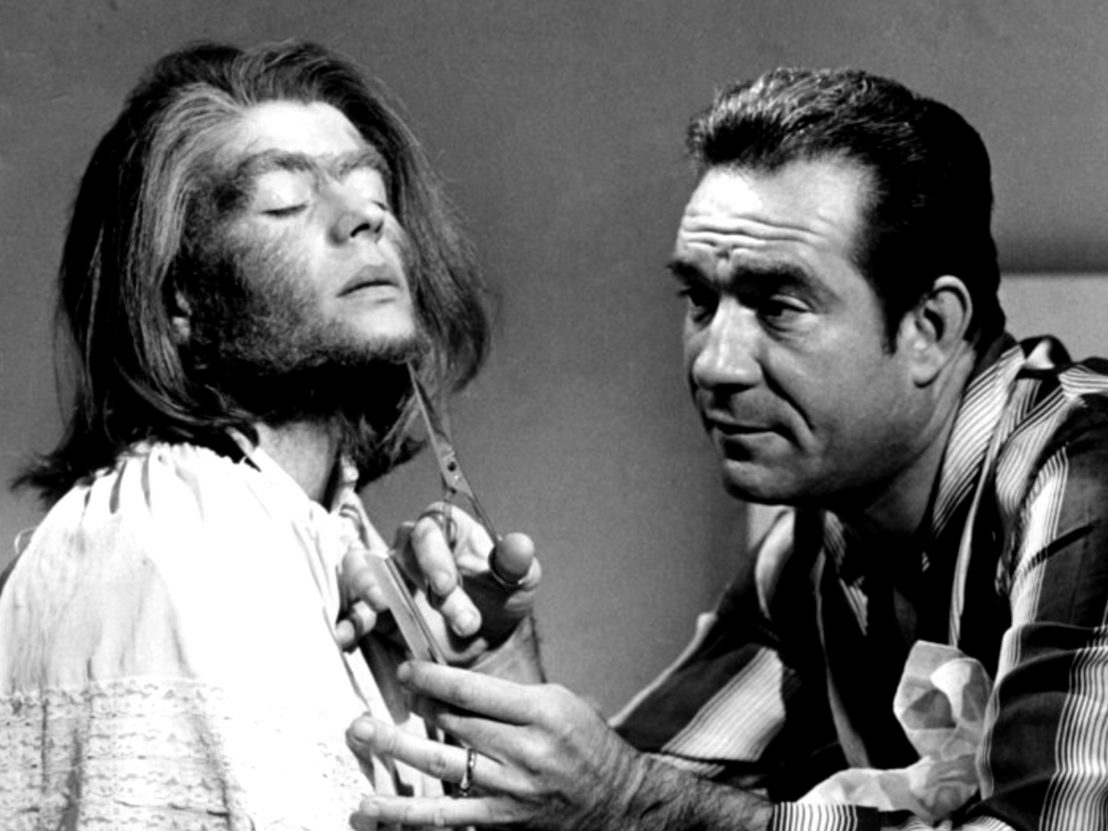

The Ape Woman is an exploitation film, in the sense that it is a film about exploitation. Its main character Antonio (Ugo Tognazzi) is, like any filmmaker, an entertainer in the business of projecting images. He is the one operating the slides at the nunnery, and when he retreats to the kitchen for some food, he meets Maria (Annie Girardot), who has grown up as an abandoned orphan within the convent’s walls, and whose face and body are covered in hair as a result of the condition known as hypertrichosis. Immediately sniffing an opportunity, Antonio takes Maria home with him and, shifting from slideshow to sideshow, makes her the star attraction in an exhibition that he bankrolls from her savings.

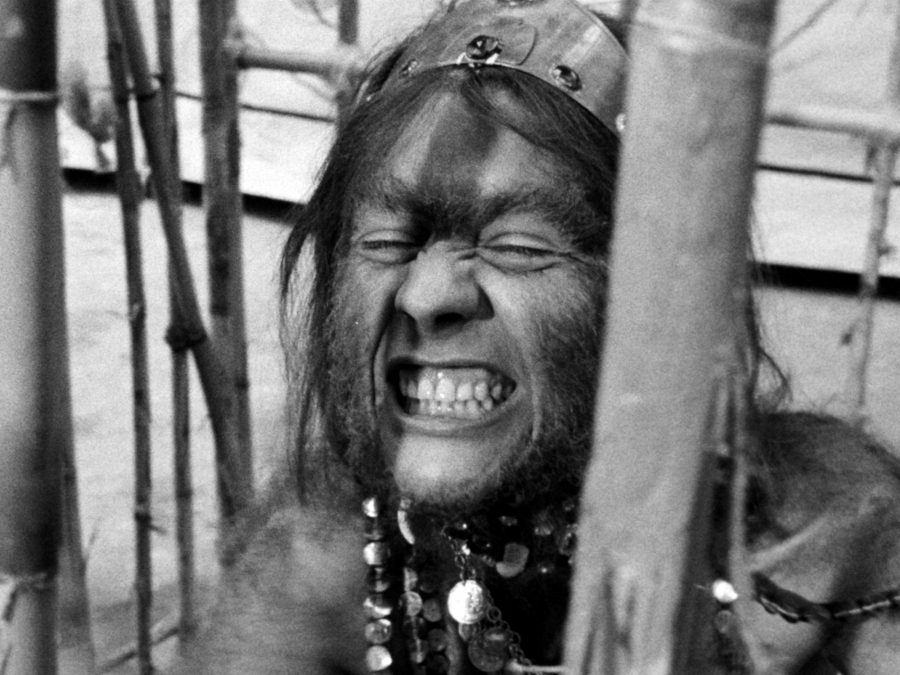

Maria is a shy young Italian woman looking for happiness, love and family. But Antonio refashions her for their show as the ‘ape woman’, claiming to have discovered her in deepest, darkest Africa. It is a show that will attract yet more male leering and unwanted groping, and Antonio’s metaphorical role as Maria’s pimp is almost literalised as he comes very close to selling her virginity to a creepy ‘professor’.

Everyone regards Maria as a ‘monster’, and even the medical and scientific community entertains fanciful ideas that she is only half human. But conversely it is Maria who recognises that the professor’s desire to pay for her defloration, and Antonio’s willingness to play panderer, makes them ‘pigs’. Later, she will use the word ‘monster’ in reference both to a doctor who recommends that she abort her unborn child, and to Antonio himself.

The Ape Woman is, among other things, a love story, although Antonio and Maria’s love is never equal. He initially marries her simply to maintain control over her (he expressly refers to their union as a business partnership), and reluctantly starts sharing her bed to avoid her explicit threat of an annulment. He even regards her pregnancy as a potential opportunity for future exploitation (“It would be our lucky break,” he tells a horrified Maria, “You and the child, both hairy. We’d make a lot of money.”).

Throughout their marriage, Antonio continues to manage and profit from Maria’s touring striptease act. In this act, the African ape woman seduces a European hunter with her erotic dance, and just as he surrenders to desire, shoots him dead with his own gun. This is not unlike the convent slideshow at the beginning of Ferreri’s film: for here Maria is cast as an othered object of perverse sexuality and dread, all at once attractive and abhorrent, exotic and empowered. This is, of course, a fantasy, markedly different from Maria’s reality.

The Ape Woman highlights the gulf between male and female perspectives on relationships in mid-20th-century Italy (and beyond), where Maria’s body is never entirely her own (“I am a woman,” she says at one point, “My husband decides for me”). In his way, Antonio does love Maria, but much as she serves his meals, she is also his meal ticket (“I’m your cook, too,” as she says, “I make minestrone, act like an ape”). Antonio’s every kindness towards Maria comes double-edged, as an investment in his own future monetary gain. It is a dispiriting picture of sexual inequality and exploitation, uncomfortably staged for the ogling viewer.

These themes came to the fore in Ferreri’s first submitted version of the film, which culminates in a grief-stricken Antonio still exploiting the bodies of his wife and child even after both have died (as actually happened in the 19th century with the corpse of a Mexican woman named Julia Pastrana, on whose true story this film is loosely based), all to the strains of the circus music with which The Ape Woman opens. It is a deeply cynical portrayal of masculinity bestialised and femininity reified, post mortem and ad infinitum, with the paying viewer as complicit enabler.

So horrified were the Italian censors that they swiftly cut the film’s final 15 minutes wholesale, which led producer Carlo Ponti to have a different, more palatable ending made. This version was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the 1964 Cannes Film Festival. Both versions work well, while yielding entirely different results, but perhaps it is most interesting (as this Blu-ray release from CultFilms makes possible) to regard the two endings in parallel, if contradictory, co-existence at either extreme of the same story – half grim reality, half romanticised fiction.

Where The Ape Woman owes an obvious debt to Tod Browning’s Freaks and Federico Fellini’s La Strada, it would in turn come to have its own subsequent influence on David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (while also lending its line “have you had sexual relations with the lady?” to Lynch’s earlier Eraserhead). It is a peculiar film, a Fellini-esque satire offering a crushing view of humanity, while also somehow finding sympathy for all its ‘monsters’.

At the end of the Director’s Cut, Antonio’s final words – “Ladies and gentlemen, esteemed spectators, I am at your disposal” – are addressed directly to camera, making the audience feel very much a part of this ugly, monstrous spectacle. After all, who amongst us has not come to see the Ape Woman?

The Ape Woman is available in a 4K restoration on Blu-ray and Digital from 11 October via Cultfilms

Published 11 Oct 2021

By Anton Bitel

Don Sharp’s Psychomania is now available on DVD and Blu-ray.

Exploring the suggestive imagery and symbolic language in the director’s 1986 cult favourite.

Anna Biller’s The Love Witch offers a playful take on a genre dominated by male perspectives.