It’s the new technology that has hollywood’s top stars running scared, but will virtual actors ever take the place of the real thing?

“Actors are cattle,” Alfred Hitchcock once said. An inflammatory metaphor perhaps, but at the height of the studio system – when actors were treated like commodities to be bought, traded and sold – these three words cut the film industry deep. In his own facetious way, Hitch had a point. Today’s movie stars sit comfortably atop the celebrity food chain, with the biggest names in the biz frequently populating rich lists and power rankings. Since the 1980s we’ve witnessed the rise of the brand actor; dominated by a select few who are able to generate vast personal fortunes through an extensive network of multimedia contracts. At a time when the global economy is in a fragile state of recovery, however, could this breed be about to see its supremacy wane?

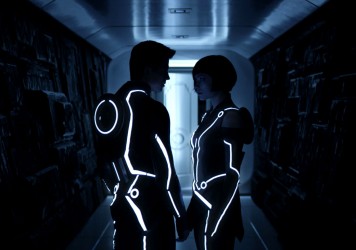

When Disney announced in 2005 that it was plugging back into the TRON mainframe for a big-budget sequel to its cult ’80s sci-fi, the first question asked was whether Jeff Bridges would be reprising his role as ENCOM CEO Kevin Flynn and his digital alter ego, Clu. To the collective delight of TRON fans everywhere, the answer was yes, but this raised another issue: Clu, being a synthetic projection in a virtual world, would not have aged physically. How, then, do you take The Dude back to 1982? Make-up or some degree of digital restoration would do the trick to an extent. But the makers of TRON: Legacy opted for something a little more radical.

In the film Bridges appears as a digitally rendered version of his younger self; captured by VFX company Digital Domain and leading special effects supervisor Eric Barba, who previously took Brad Pitt through the seasons in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. “In creating a digital Jeff, we first had to take a life cast,” explains Barba. “We got Jeff into our Nova contour rig, much like we did on Benjamin Button, and we were able to do a library of face shapes from him.

“It’s actually pretty complicated,” he continues. “There’s a rig made, and that rig is driven by an animator, with everything referencing back to the library of shapes that came off Jeff’s face. We put a four-camera head-rig [on Jeff] during principle production so he could step in and do the lines, walk out of scene, and then we would get an animator in, who was watching off- screen, who we would shoot the actual scene with. Once we had the four-camera selects, we would pick up the data and those points would be tracked by a computer.”

To all intents and purposes, the Jeff Bridges in TRON: Legacy is not Jeff Bridges. But as Barba reveals, Bridges’ presence in the early production stages was essential for the animation team. “Because the tracking points live in 3D space, we had to apply them to an algorithm we wrote that we could then compare to the archive of facial shapes. But the algorithm, as sophisticated as it is, doesn’t know the difference between, say, a happy smile or a sad smile or a surly smile. So we had to look at Jeff and just make those adjustments. The nuances in human expressions are so fine, the little things that you see, and the computer may say, ‘Well this is what the shapes did’, but it may not come across quite the same. You have to manually tweak it. And you keep tweaking it until it feels just right.”

Although the intricacies of this complex motion capture process might not seem entirely novel in contemporary VFX terms, Digital Domain is way ahead in charting the virtual actor frontier. And, as Barba suggests, TRON: Legacy will be looked back on as the first ray of a new dawn. “After working on Benjamin Button, people asked me if what we did with Brad Pitt would open up new avenues. I think TRON: Legacy is the first real step forward in that sense. Much like the first dinosaur we saw walk in Jurassic Park, we’re breaking new ground now.” He continues: “It’s still an incredibly difficult process, particularly in terms of getting the persona of the character right. It’s still in the artisan stage. It’s not in the push-button stage yet.”

No one can yet predict how far this innovative digital art form can be taken. How close are we to being able to replicate real life actors using CGI? Could we ever get to the stage where virtual actors could replace humans? Could the two even become indistinguishable? Perhaps not entirely, suggests Paul Franklin, visual effects supervisor on Inception.

“You can use digital effects to make creatures or whole characters, like in Avatar, but they are driven by a real performance underneath,” he says. “There will always be a role for actors inside that somewhere – whether they are in a motion capture rig or whatever – and audiences will always respond to real human emotion. So whether you’re filming an actor directly or interpreting them through computer graphics, there’s always got to be that emotional core. Computers will never, or at least not for a very long time, be able to spontaneously generate that.”

In the case of the TRON franchise, however, Disney now has an entire catalogue of digital shapes individually assigned to Jeff Bridges’ facial expressions. If additional instalments are greenlit, could the real Bridges potentially be rendered superfluous? “I think that’s the actor’s fear,” says Barba, “but I’ll be the first one to say, ‘I need Jeff.’ Jeff makes Jeff ‘Jeff’. Jeff does things no one else does; you can’t have an animator doing that. It won’t come across as Jeff. Without the guidance of Jeff’s performance, it wouldn’t look like Jeff as soon as he moves. Jeff moves his face in a particular way. If someone else moves his face, it instantly stops being Jeff.”

At present the technology relies on a physical template, but as animators become more adept at replicating actors’ expressions and gestures, there may be nothing stopping future generations of filmmakers adding entire chapters to familiar stories without an actor inputting information beforehand. “There’s a whole generation of filmmakers coming through who are completely at ease with this kind of work; guys who have grown up in a world of computers and videogames,” explains Franklin. “They don’t see it as a threat; they just see it as another part of the filmmaking process.”

As Hollywood continues to eat itself, remakes and reboots are now par for the course. But what if a studio decides it wants to regenerate public interest in a franchise whose star attraction is now unavailable – be it through death or illness – or simply unsuitable for the part because of age? While MGM looks increasingly unlikely to be able to meet Daniel Craig’s asking price, thus beginning the search for the next Bond, why not turn to technology and restore a younger, fuller-haired Sean Connery to the role? Cine-purists might shudder at the thought, but if a digi-Bond was offered at a fraction of the cost of the real thing, you can bet studio executives would at the very least entertain the idea.

With an estimated budget of $150 million, the animators on TRON: Legacy had the financial means to realise this new blueprint for the virtual actor. But what happens when the formula becomes more affordable? “Computers are getting cheaper and more powerful all the time, so you’ve got a straightforward increase in horsepower behind what you can do for the same price,” says Franklin. “This time next year I could do certain things on Inception for a reduced price, which then increases the scope for what the filmmaker can do.”

As the creative process gets cheaper, the possibilities become infinite. But how might this impact the future of conventional acting? In this post-Brando age, where few working screen actors can claim to be true pioneers of their craft, does the digital medium simply represent the next step? Barba reckons so. “I love humans. I love actors. But I think there’s a place for this technique when you have to bring someone back or de-age them or tell a story you couldn’t ordinarily tell. It might only be an interpretation with today’s technology as it is, but there’s no reason why you couldn’t bring back some of the great names some day.”

Regardless of when the technology arrives, however, are audiences ready to embrace digital reincarnations of screen icons? The success of Avatar and Benjamin Button suggests so, but if computer-generated actors are ever to compete with the real thing, animators like Barba must first overcome a number of obstacles, namely an anthropomorphic phenomenon known as the ‘uncanny valley’.

Coined by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori, this term denotes the point at which the level of verisimilitude achieved by robots and other facsimiles of humans causes a negative emotional response from the human observer. In Mori’s proposed graph, the positivity of human reaction plotted against the anthropomorphism of robots hits a dip – or ‘valley’ – at the point of ‘almost human’ realism. Put simply, the more realistic a robot appears, the more likely we are to find it unsettling. Every virtual performance is relative to the skill and artistry of the individual animator, but the more frequently well-recognised actors are copied or digitally resurrected, the higher the likelihood of imperfections, no matter how discreet, being amplified becomes.

As Barba admits, the greatest challenge facing his trade is finding a way to trick the human mind. “From the day we come out of the womb, we see other human faces. Whether it’s a baby in Africa or Indonesia or the United States, the expressions a human face makes, regardless of language or culture, are inherent to our species. A smile is a smile. We learn to read these nuances instantly – we don’t even think about it. The same thing applies with a CG head – you read it instantly. And when it’s not right, you know it’s not right. It comes down to an infinite amount of subtleties, whether you hit enough of them so that the audience instantly buys the performance. When you nail it, it’s magic. When you miss it, you’re back in the valley.”

For now, this phenomenon poses the single greatest threat to the development of virtual acting. But the current rate of technological progress may well dictate a shift in attitudes. As a concept, virtual acting is still very much in its infancy, but this is a science, not a gimmick. It may be hard to imagine a time when flesh-and-blood stars have become completely outmoded, but at $80 million a pop, it’s no wonder Hollywood is so keen to nurture the growth of the virtual actor. One thing is for certain: the game is changing. The revolution sequence has been initiated.

Published 15 Dec 2010

The gap between movies and video games is closing. But what will happen when the viewer has control over the script?

By Tom Seymour

The screen may glow in Joseph Kosinski’s sci-fi spectacle, but the soul lies cold.

Xavier Dolan’s open letter to Netflix highlights a wider issue concerning the way movies are consumed in the digital age.