This year marks half a century since man first landed on the moon, but on the horizon is a new era of space travel. NASA has announced that from 2020 the International Space Station will be a new destination for tourists who have exhausted every other instagrammable spot on Earth. But should we be wary of this next giant leap in humanity’s upward journey? Exploring celestial notions of human evolution and development, Danny Boyle’s 2007 sci-fi thriller Sunshine shows the beautiful and dangerous possibilities of space travel in the year 2057.

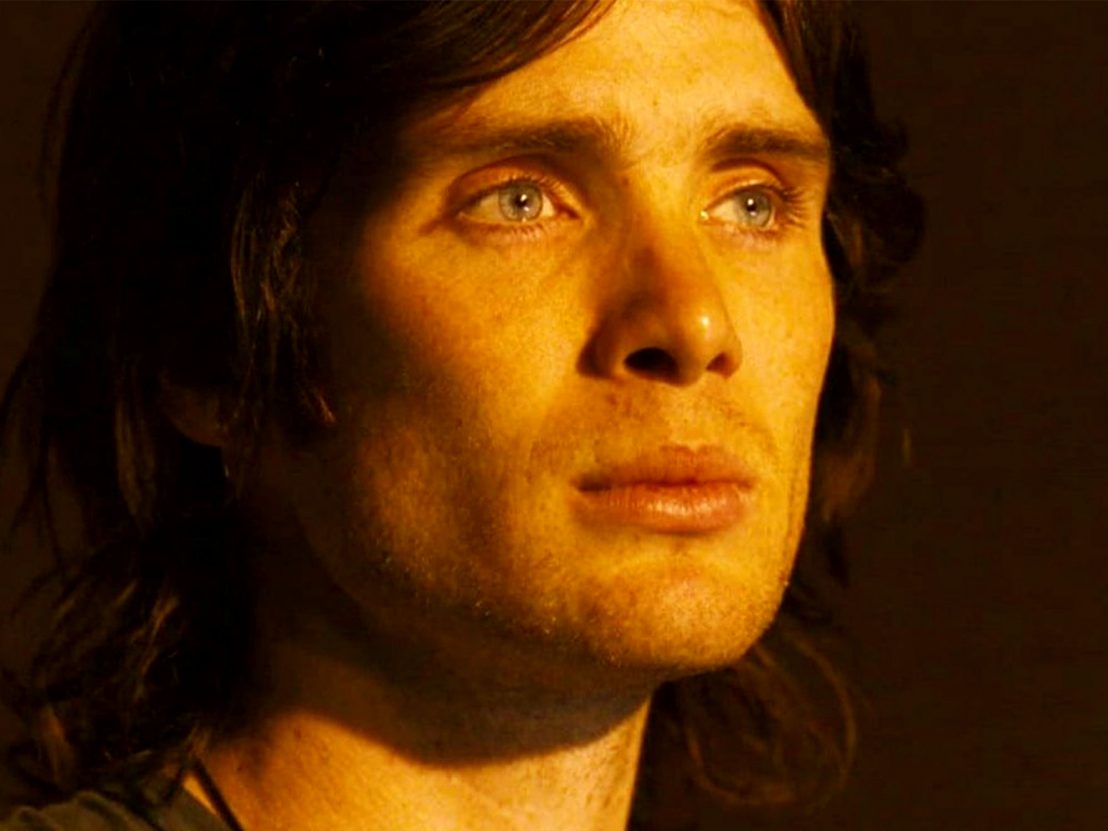

The film introduces space travel as a method of survival as eight astronauts embark on a mission to re-ignite the sun. As the destination of the Icarus II ship, the sun comes to represent more than just a life-giving source: it is a symbol of hope; a shining light in the darkness. Yet just as the Greek myth of Icarus tells, we learn that the original Icarus ship stopped flying. The Icarus II ship suffers a similar fate. As the ship slowly begins to break apart, so does the community on board. Moments of sheer panic and mayhem ensue as the crew scrambles to replenish their oxygen supply and races against the clock to ensure the ship’s airlock is secured. From humanity’s perspective, space travel is instrumental to Earth’s survival, the only available option to solve the issue of extinction. But it comes at a price.

One setting within the film that is emblematic of the relationship between humanity and space is the Icarus II’s observation deck. The area consists of a floor-to-ceiling window through which the crew can gaze out at the solar system. The views are truly spectacular, and the characters derive a distinct pleasure from staring into the vastness of space. It seduces them completely, leaving them awe-struck at the never-ending expanse of the galaxy. From the deck they are able to see the future of their exploration, and this is effectively what NASA is promising with its space tourism initiative.

As the film unfolds, discussions of morality come to the fore. The Icarus II crew are repeatedly asked to consider the value of human life. Capturing the existential dread of trying to prolong one’s own existence, the film reveals the cost of scientific and human progress. Central to this is a debate around mental endurance, and as the Icarus II continues to move forward, the crew find themselves butting heads with conflicting attitudes. Unable to escape the enclosed confines of the ship, the enormity of outer space becomes a cruel juxtaposition to the claustrophobia they experience. Without home comforts or a sense of grounding, they are left alone with each other and their thoughts.

This desire to venture forth and make new discoveries took seed long before Neil Armstrong took the first human steps on the moon. Sunshine simply extends this adventurous spirit. Among the film’s bleaker scenes, there are moments of optimism which speak to the power of the human spirit. While the film proposes space travel as a perilous but logical next step in human evolution, it repeatedly draws our attention to the determination and formidable strength of the crew. Humanity may seem minuscule in comparison to the grandeur of space, but crucially Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland emphasise the importance of feeling present in the universe.

One line from the film that best summarises the relationship between humanity and space comes from Cliff Curtis’ Searle: “We’re only stardust.” The notion of there being an intrinsic connection between human beings and the wider universe is woven into Sunshine’s narrative fibre. In 38 years, NASA’s goal of democratising space travel may have been achieved. Perhaps even on a level as advanced to carry out the challenging journey that is represented in Sunshine. But one thing remains certain: people will always be fascinated with the stars, even when they are among them.

Published 16 Jul 2019

Director Todd Douglas Miller reflects on the completion of a cinematic mission 50 years in the making.

Half a century on from mankind’s giant leap, this documentary brings the mission back to life in stunning clarity.

By Thomas Hobbs

The revelation that Lambert is a trans woman transforms what we know about Ridley Scott’s sci-fi horror.