In 1981, an otherwise quiet town outside of San Jose, CA became the epicentre of a media frenzy and an attendant moral panic. A high school boy had murdered his girlfriend and left her lifeless body where it fell. The homicide then went unreported for two days while he invited his friends to come and gawk at the girl’s corpse. Commentators immediately seized upon the case as a symbol of a whole generation’s callous amorality.

When a film loosely based on those events, River’s Edge, was released in the summer of 1987, it was destined to become the most disaffected of ’80s teen movies. Keanu Reeves stars in his first major role as a baby-faced stoner. His wild little brother is among the first to discover the body, but soon the whole slacker clique is involved. They’re seemingly unwilling to report the perpetrator Samson (Daniel Roebuck), especially speed freak Layne (a twitchy Crispin Glover, donning a leather get-up reminiscent of the ghosts of delinquents past). The teens gather around to regard the nude body of their mutual friend with cold fascination, but little actual feeling.

Tim Hunter’s vision is of an American nightmare, where teens like Layne cheerfully endorse murder and uphold a bizarre code of loyalty to one another. Meanwhile, a local drug dealer named Feck (Dennis Hopper at his paranoid best) is the only adult that the kids seem to feel comfortable confiding in. Even more troubling is Feck’s insistence that he’s hiding out after murdering his own girlfriend. At best, the parents of these wayward teenagers barely seem able to cling to the semblance of control. At worst, their family dysfunction is endemic and impossible to rectify – making the sort of parent-child disruption of John Hughes’ films seem positively cosy.

Clarissa (Ione Skye) and Matt (Reeves) finally decide to go to the local cops – and even that seems more like an empty gesture of moral righteousness than a genuine impulse. So begins a nocturnal odyssey across the overgrown environs of the neighbourhood, which has a down-and-out Rust Belt feel and an air of unpredictable, building violence.

The self-absorption of the teenagers in the film is evident when a TV news anchor comes to school to report on the shocking events. The response is preening and self-aggrandisement, faux-emotion and pretend moral judgement. The kids of River’s Edge are lacking something, though it’s never entirely clear what that thing is – warmth and guidance, a moral compass, or simply the direction of a decent upbringing. The film may be a touch moralistic, but given John Hughes’ parallel vision of adolescence – one that’s aspirational and idealistic – River’s Edge is also strikingly unhinged. Crispin Glover bullies a child and Dennis Hopper waltzes with a blow-up doll. That bizarre, nihilistic flavour transcends whatever cautionary impulses the film has. Where Hughes offers hopeful romanticism, Hunter reveals only dead ends.

Feck, the Hopper character, serves as a kind of twisted surrogate parent. In a handful of films of the ’80s, the actor came to be representative of ageing ’60s hippiedom, mired in psychosis and vice. As such, his burnt-out flower child persona seems like a let-down to Reagan-era teens, who are lost in the fading wake of a meaningful subculture. After the rise of the so-called ‘New Right’ of the late ’70s, large parts of radical youth culture had been subsumed into the mainstream. The counterculture was in its death throes, and even the punk movement had faded into incoherence.

With little to distract or gird them from the cruelty and hopelessness of the adult world, teens form their own tribal affiliations. Numb to the hippies’ call for peace or punk’s ethos of rage, the kids of River’s Edge have been left to their own devices. When Feck, the only adult, pulls the trigger, it’s a clear reminder of something. If the youth of the nation is morally and spiritually bankrupt, then they only learned it from their parents.

Published 20 Jun 2017

By Tom Bond

Rob Reiner’s touching drama sees four friends say goodbye to the safety and stability of childhood.

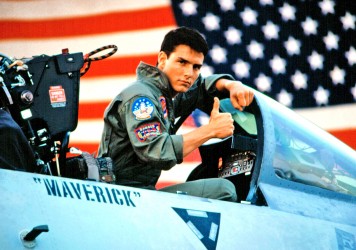

A first-time flyer attempts to glean the plot of this cherished Tom Cruise vehicle from 30 years of pop culture collateral.

As Heath Ledger and Julia Stiles taught us, being young isn’t about fitting in but forging your own path.