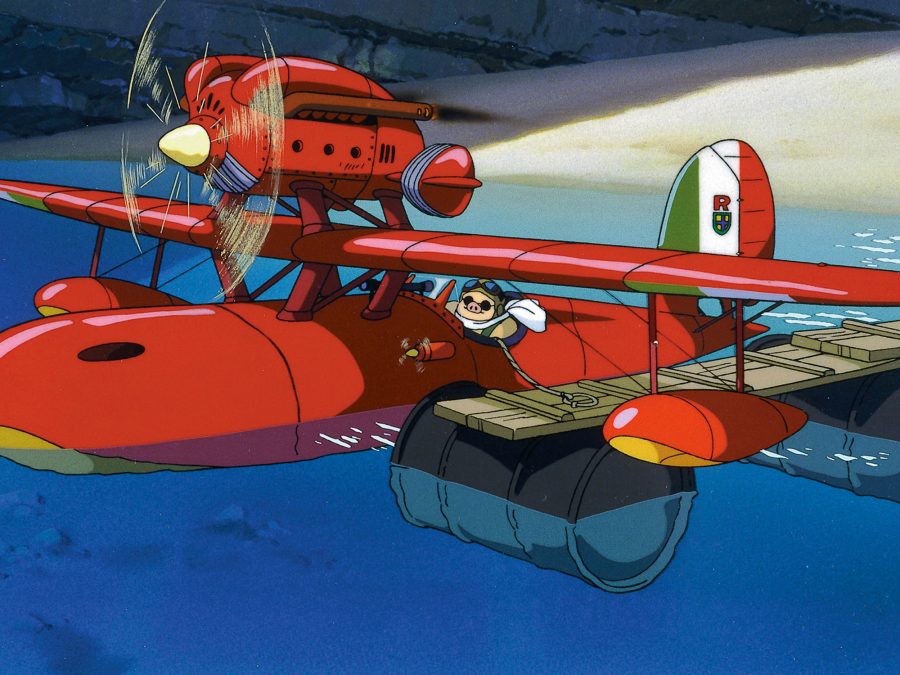

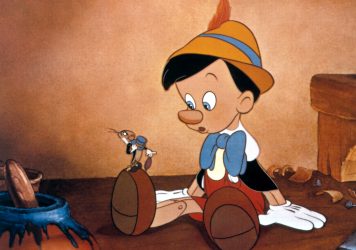

In separate corners of a fantasy-tinged 1930s Italy, two famous stories play out concurrently. Guillermo del Toro’s take on Pinocchio sees a puppet come to life in a small village, while on the borders of the country, Hayao Miyazaki’s anthropomorphic pig Porco Rosso rests in his Adriatic hideout.

Viewing the country through the eyes of each of these directors provides a profoundly different picture stylistically. Miyazaki’s protagonist is a war veteran, disenfranchised by nationalism and making a living off bounty hunting. Del Toro’s Pinocchio is a walking, talking newborn, a ball of energy and wonder. Despite this, the two are in agreement ideologically. Both del Toro and Miyazaki use the setting of Mussolini’s Italy to disparage the idea of fascism.

In the west we like to treat fascism as something that died after WWII, but recent events across Europe and the Americas have shown this to not be the case. Italy’s new government is full of Mussolini supporters, Brazil’s latest election was a fight to retain rights for the LGBTQ+ community as well as the indigenous population, and the views of UK Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, are fear-inducing for anyone with non-British ancestors.

An understanding of who the victims of fascism are, what it’s like to exist under a fascist regime and how to resist the lurking threat of fascism should be common knowledge, but so many of us refuse to learn from our history. Whether it’s Miyazaki’s colourful, hand-drawn masterpiece or del Toro’s darker, worn stop-motion spectacle, it remains devastatingly essential for these stories to be told again.

As vehicles to represent rebellion, Pinocchio and Porco occupy opposite ends of a spectrum. Pinocchio is essentially a new-born. His first musical number in del Toro’s film is a ballad dedicated to learning the names of everyday objects and an ode to childlike wonder. Meanwhile, Porco Rosso is a world-weary war veteran who is extremely aware of the systems in place around him and actively looks to lead a quiet, independent life.

Pinocchio’s rebellion comes from his naïveté. With no concept of what fascism is, and therefore the public order which is expected of him, he is free to see the world as a playground. He came into the world with a boundless curiosity and a desire to explore a country where everyone else is too terrified to step out of their designated paths. Pinocchio’s repeated ignorance of the pleas from those around him to “obey” is rebellion against Mussolini’s fascism, despite how unintentional it seems.

Age and jadedness breeds rebellion for Porco Rosso. His exploits as an Italian fighter pilot in WWI saw him end up as the sole survivor of his squadron and inexplicably cursed to live out the rest of his days as a pig. This curse can be read as the survivor’s guilt and PTSD he carries from the war. He has been on the front lines of the worst humanity has had to offer, and can immediately recognise fascism for what it is. Porco made a life for himself as a seaplane-flying bounty hunter operating from a hideout in the Adriatic Sea – a rare show of independence under a fascist system. Retreating from mainland Italy, Porco is able to maintain his sense of self in a system that wants to put him in a box.

The European setting for both stories is conducive to their allegories about racism, and how racism is weaponized by fascism to protect order. Both of our protagonists have distinct visual features that other them in every setting. For all the talking animals and mystical fairies that exist in Pinocchio, the puppet is still described as an “abomination.” Even Miyazaki plays down the magical realism to set a clear boundary between the harsh realism of fascist Italy and the half-man half-pig at the centre of his story.

“Pig” is as close to a slur as you’ll hear in a Miyazaki movie. Its function in Porco Rosso is to other and insult Porco, spat from the mouths of the seaplane pirates who Porco frequently thwarts. Partly due to self-loathing and partly due to self-confidence, Porco reclaims the word “Pig”, internalising it and using it to celebrate his differences from the Mussolini-worshipping humans around him. Emblematic of this message is a conversation Porco has with a fellow pilot and Italian army sergeant who encourages him to seek the protection of the Italian military. To his pleas, Porco responds with the iconic line “Better a pig than a fascist.”

The miracle of Pinocchio’s existence is immediately dampened by Gepetto’s horror at his creation, later joined by the rest of his village. His humanity is called into question as calls for his death and references to the boy as “it” and “thing” flow from villagers’ lips. As with Porco, words are used to cast shame on Pinocchio for his existence as anything other than the white monolith of fascist Italy.

Western society mimics this technique of suppression to this day, placing labels on minorities that dampen their perceived worth to society. Pinocchio is free of any system that programmed him to pre-judge. At the centre of del Toro’s story is the irony of the literal puppet being the most free in a land of people on strings from the hands of a fascist leader. Our physical differences can be emblematic of ideological differences. Fascist structures see racial diversity as a threat to order, simply being a live black or brown person is resistance to that.

It is difficult to label western society as ‘progressive’ when stories set almost 100 years ago feel like they are pressing against the neck of the current establishment. Miyazaki and del Toro’s films are reminders that we still have so much to learn from our history, that lessons expressed through art are just as powerful as those learned through textbooks, and that art has the ability to change attitudes and shift ideologies.

Porco Rosso and del Toro’s Pinocchio show that rebellion against an oppressive system doesn’t have to look the same, in fact, the wider the range of rebellion the better. The films also show how the weapons of fascism hit hardest on the backs of minorities, reflecting how entrenched in the cycle of rising fascism we are today.

Art that reminds us why we resist, and how we resist, should be used as a roadmap through the coming years of political discourse. Fascism breeds on belief in the system over belief in the self – Porco Rosso and Pinocchio tell us that the latter is forever more important.

Published 22 Nov 2022

By James Clarke

On the 80th anniversary of Disney’s animation, we look at the different ways this magical fable has been interpreted.

Matteo Garrone’s live-action retelling of the classic Italian fairy tale is a dream come true.

Access an exclusive virtual preview of the Rock Against Racism film, in association with All Points East.