In the summer of 1960, as Japan’s Anpo protests raged on, nearly a third of the population took the streets in resistance to the U.S. Japan Security Treaty. The greatest implication of the agreement was that it allowed the United States to establish bases across the Archipelago. For the socialists, communists, women’s organizers, and students who opposed it, this was the boiling point of a longstanding battle between peace and the return to militarism. The wave crescendoed on June 15th, when hundreds of thousands of protestors stormed the National Diet compound. As the sun came up slowly, Yoshida Kiju was busy editing one of the two directorial debuts he would release later that year. As he reflects in his 2010 manifesto: “Finishing the film on that day was perhaps, in some sense, chance.”

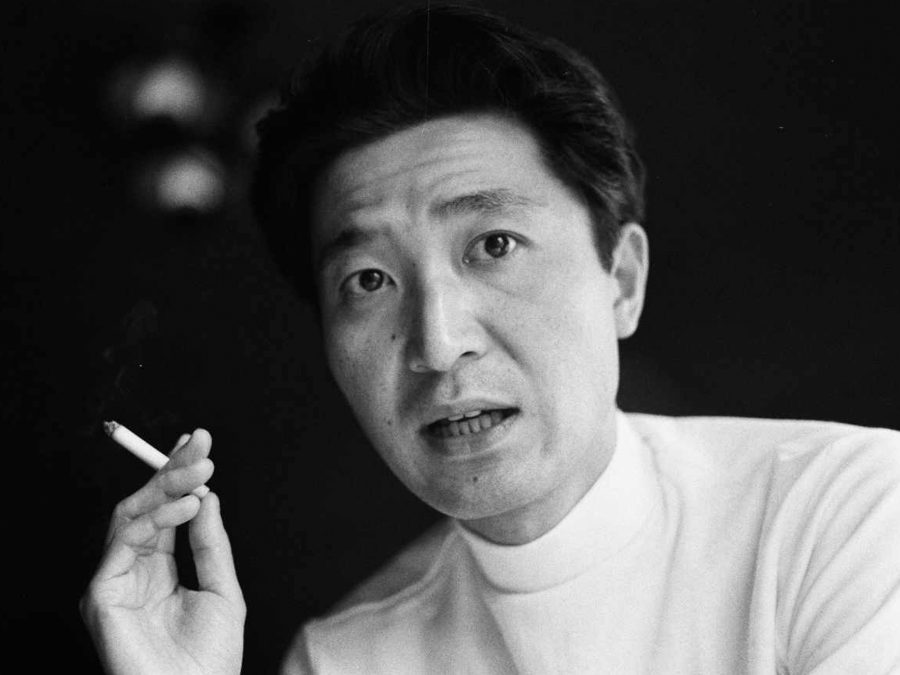

Yoshida passed away last month at the age of 89. He was a founding member of what was dubbed the New Wave of Japanese cinema – a creative movement that began in the early 1960s during a period of violent social unrest throughout Japan. Along with his peers, he challenged previous conventions through subjects like radicalism, sexual violence, and commodity fetishism that underpinned the “bright life” of Japanese modernity. His second film, Blood is Dry, is an interesting case; it was pulled from the production company just three days after its premiere when the leader of the Japan Socialist party was assassinated on live television. As such, it is surrounded by an obscurity not shared by his anti-melodramas like Akitsu Springs, or magnum opus, Eros + Massacre. Part anti-capitalist reflection, part call to action – Blood is Dry holds its own today as a unique, anti-humanist voyage through the dynamism of the Japanese 60s.

The film begins when a salaryman named Takashi Kiguchi is laid off from his job; he then makes a dramatic, failed attempt at shooting himself in the head. A life insurance company gets wind of this story and decides to hire him as the mascot of their new ad campaign – literally selling suicide under the slogan: “It’s high time that you are all happy.” He reluctantly agrees, and after a staged photo reenactment, his image is plastered all throughout Tokyo. What follows is a narrative dance between a slimy paparazzo (Harada), Takashi’s ad agent (Ikuyo), and Takashi as they set out to exploit, control, and destroy one another.

With the setting of Tokyo, Yoshida gives form to 1960 Japan through collisions of space, culture, and time. Erratic cuts carry the audience between blind rooftops and street corners while the intimacy of the home is breached by voyeuristic photography. Meanwhile, the cast repeatedly enters into 1940s American noir through the world of a smokey jazz club. Even Takashi’s pistol contains a matrix of overlapped meaning, as it is both a relic of imperial Japan, and a copy of the gun used to assassinate Franz Ferdinand at the start of World War One; it emerges once again into the present as an inconvenient zombie.

It is through such collisions that the film evinces the spatial and temporal incoherence of 1960 Japan: a country that had conquered violently, and was killed for it; had been turned to ash, occupied, and blistered; was rebuilt upon the hot layers of itself, and appeared at the doorstep of a new decade as a budding protege of Western modernity. Like his New Wave contemporaries, Yoshida reflected on this historical moment with heavy skepticism.

Japan was democratized, yet its labor movements were being squashed from above; it was demilitarized, yet it had just helped America wage a violent war in Korea; it was promoting a “bright life” under capitalism, yet much of the working class had fallen into debt trying to afford televisions. What Yoshida saw was not a country on the precipice of greatness, but rather, as Ikuyo muses, “… a house of cards,” suspended only by the lattice of its own contradiction.

As such, Blood is Dry represents a pivotal shift from the humanism of Japanese postwar cinema; in these films, mankind was paramount; it contained both an inherent authenticity, and an infinite potential for self-determination. In contrast, Blood is Dry asserts the supreme will of its world. Characters are not guided by the power of human spirit; rather, they exist as vessels of the disjointed objects, places, and conditions that surround them.

One way this logic manifests is through the character arc of Takashi. Soft-spoken and withdrawn, he erupts rapidly into public stardom. He finds himself cast as an omnipresent advertisement, and then as a figurehead of a worker’s union. As his passivity is replaced by hubris, Ikuyo tries frantically to reel him back under her thumb – herself only a vessel for the financial interests of the company. In one scene, they stand together under the sublime presence of Takashi’s billboard; he stares back at himself, possessed by headlights, and bellows: “This is what I am!”

In this way, Blood is Dry deconstructs the trope of stoicism found in films like Kurasawa’s Seven Samurai. Like these prolific heroes, Takashi is initially reserved. Yet instead of cutting through the nonsense of the world, this stoic nature is stripped naked, and shown to be as mutable as anything else. When his personality fractures, we are met with the unsettling suggestion that he was never even real to begin with.

Harada, on the other hand, exudes control from the very start: “I crush anybody I don’t like.” In another timeline, with his hate of corporatism and suave demeanor, Blood is Dry could have easily billed him as its anti-hero. Instead, when he takes pictures, we are given long closeups of his camera, and not him. When he steals power – often through deceit and sexual violence – he is unable to wield it effectively, so nothing changes. The film does not deliver Harada to us as a lone wolf; rather, he is unraveled as a vehicle of class-based frustration, functionally adrift, and led mostly by the will of his camera.

The result is a cast always entangled in repetitive loops. Takashi tries to kill himself, and then spends the rest of the film mimicking that same act for posters and commercials. Harada coerces a famous baseball player to drink, stages intimate photos, and then smears their reputation; he destroys Takashi in much the same way, and in both instances, he is physically beaten as a result. Ikuyo is always beckoned back to the jazz club, where she dances in circles and eventually goes home with Harada.

In a quiet moment near the film’s climax, they lay in bed together naked and outstretched. We listen to the dead rumbles of a 24-hour factory. Ikuyo speaks as if caught in an endless, cyclical dream: “I slept with you years ago, today I’m sleeping with you again.” She drags a cigarette under the moonlight, “It’s as if I did nothing. It’s truly bizarre.”

It is here that we arrive at Blood is Dry’s fundamental conflict: a perpetual inability to reimagine the future. For Yoshida, living in Japan during the sixties was an, “absurd situation.” It provided tangible evidence that there was no natural state of things – no bedrock of meaning on which to rely. Thus, the only path forward was to first meet eye to eye with one’s conditions. In the end, he forces us to do this with Takashi’s closing act.

After being defamed and fired, Takashi storms corporate headquarters. He draws his gun to his head, and finally – after countless imitations of the original attempt – pulls the trigger. The closing minutes drag on with our protagonist dead as reporters are sent into a frenzy trying to understand why. When his billboard falls magnanimously from its resting place, the camera zooms in slowly on Takashi’s crumpled face. He is no longer a man, only the pure, unobscured image of everything that animated him – his job, the advertisement, and of course, Harada and Ikuyo. They watch him, perhaps clearly for the first time. Credits close over Tokyo and the loop is broken at last.

Published 20 Jan 2023

Don’t fear the run-time: Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s giant saga is a movie for the binge-watching generation.

By Anton Bitel

Destruction Babies is raucous rebel filmmaking at its brutal best.

The shining star of movies by Ozu, Naruse and Kurosawa has died at the age of 95.