A number of critics have objected to Quentin Tarantino’s movies on the grounds that the violence he unleashes upon his female characters is in service of nothing but his own entertainment. After watching The Hateful Eight, Laura Bogart wrote that one of the only female characters of the film (Jennifer Jason Leigh’s Daisy Domergue) is “somehow singled out for the most savage treatment – and not only by the men on screen, but by the man behind the camera.”

In a recent piece in The Guardian, Roy Chacko argued that Tarantino’s films revel in “extreme violence against female characters” and are evidence of “the director’s fondness for piling abuse on women.” It’s not just the fact that people do horrible things to women in Tarantino’s films, the argument goes, but that his camera delights specifically in female suffering.

Tarantino’s films do revel in a certain type of violence, one that is simultaneously messy and disgusting and cool and slick; a violence that ends with gunshot wounds that squirt blood cartoonishly; a violence that makes sweaty, beautifully lit faces contort in pain at 24 frames per second. Yet the claim that Tarantino directs heavily stylised, often extremely graphic violence at women for his own perverse, juvenile pleasure is both fallacious and dangerous.

Firstly, this implies that his male characters do not suffer in the same way. But in The Hateful Eight, everyone screams and bleeds. Major Warren (Samuel L Jackson) is shot in a sensitive area and the grizzly John Ruth (Kurt Russell) projectile vomits an unbelievable amount of blood. Yes, like her male counterparts, Daisy is severely punished, and this makes for grossly entertaining, uncomfortable viewing. Of course it does. It’s meant to.

But the point of her suffering is neither misogynistic nor comedic. Paradoxically, she is beaten black-and-blue in the name of equality. As Tarantino explained to Variety, “Violence is hanging over every one of those characters, like a cloak of night. So I’m not going to go, ‘Okay, that’s the case for seven of the characters, but because one is a woman, I have to treat her differently.’ I’m not going to do that.”

The accusation that Tarantino’s films are misogynistic also implies that the women in them are one-dimensional punching bags, rather than fully-formed characters. Again, this is simply not true. Over the course of his career, Tarantino has brought us a variety of strong, complex female characters. One might even argue that his films are ingloriously feminist. Which is to say that while Tarantino is not necessarily someone who consciously sets out to make films about female empowerment, he does promote female agency through writing multifaceted women.

Jackie Brown is a prime example of the inglorious feminism latent in Tarantino’s work. At the end of the film, Jackie (Pam Grier) is alone and driving to the airport with half a million dollars in her suitcase. The camera lingers on her for the entirety of the scene, allowing us to observe her as she smiles and sings along to Bobby Womack’s ‘Across 110th Street’. As she sings the line “pimps trying to catch a woman that’s weak”, we suddenly notice her content expression changing and her eyes slowly begin to imbue a sadness. Or is it fear? We can only guess at what Jackie is thinking. She might be thinking about those sun-dappled LA streets she’s driving through. They’re her home, after all, and she’s leaving them behind to start afresh in another country.

Whatever is on her mind, there’s no denying that this brief display of emotional fragility is a subversive narrative choice from Tarantino. Here is a woman who up to this point has been outwardly decisive and strong-willed – an archetypal feminist hero. She’s already reduced murderous gun-dealer Ordell (Samuel L Jackson) to a well-behaved Labrador. “Shut your raggedy ass up and sit down,” she exclaims after he points a gun in her face, and sit down he most definitely does. She has also managed to turn charming bond salesman Max (Robert Forster) into a lovesick teenager. Max is both head-over-heels-Delfonics-in-the-car in love with Jackie and also absolutely terrified of her. She knows all this, but still plays him for kicks. “Are you scared of me?” she asks. There’s a slight pause as he thinks. He then puts up two fingers close to each other and sweetly replies, “A little bit.”

Tarantino is a screenwriter who has always shown a sincere affinity for his characters. Big or small, everyone is given their own moment to shine, even if it’s just for a quick scene – think of Christopher Walken in Pulp Fiction, or Vivica A Fox in Kill Bill. Yet there’s something special about the love Tarantino shows for Jackie Brown (a character who, ironically, wasn’t actually conceived by him but the author Elmore Leonard in his 1992 novel ‘Rum Punch’). He loves her enough to present and centre her as a strong and fragile woman. She’s fierce and complicated; a woman wounded by time (“I just feel like I’m always starting over”) but also determined to beat time and become something more. And Tarantino grants her space to work all this out.

We watch her live, hurt, love. It’s messy, chaotic and hopelessly, beautifully human. It feels only right, then, to end the film on a note of indeterminacy. As she drives away, a profound sense of humility washes over Jackie. She is left wondering about her unknowable future, and so are we.

Published 11 Aug 2019

Stars and worlds collide as Quentin Tarantino serves up his most thoughtful and personal work to date.

The director’s own professed black sheep is his most beautiful work.

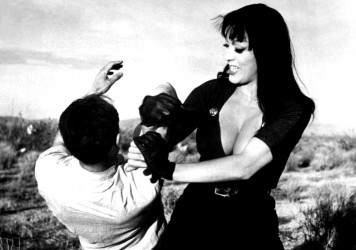

How many ’60s exploitation movies have you seen where women get to smoke, drink, drive and fight?