It’s now 20 years since Pokémon: The First Movie was released outside of Japan – and the film’s producers really weren’t lying with that title. Since 1998 there have been 20 animation sequels, with a live-action spin-off, Detective Pikachu, due out this year (following the box office bomb Pokémon 5, they’ve been primarily released direct-to-video)

The success of the original video games series is often attributed to the ingenious marketing slogan ‘Gotta Catch ’Em All’, but that alone would have produced a passing fad. Pokémon has endured as a cultural phenomenon primarily because it taps into universal themes, in addition recognising children’s innate interest in collecting: franchise creator Satoshi Tajiri cites his childhood hobby of collecting insects as a key inspiration.

Equally crucial is the way the games actively encouraged players to connect in the pre-internet era. Gaming in the ’90s was generally considered a solitary experience, but Pokémon made it sociable, quenching gamers’ desire to unite and do battle together. The appeal of Pokémon Go, the augmented reality mobile game released in 2016, was the interactive, social experience it offered, prompting users to get off the sofa and explore the outside world. It engendered a strong sense of community, and for a fleeting moment Pokémon Go meet-up groups were all the rage.

So when Pokémon: The First Movie arrived three years after the first game, many fans complained that the storytelling failed to match that of the games. Critics dismissed it as forgettable nonsense – less a movie than a marketing exercise. Rewatching the film today, the message seems no less confusing. The premise, concerning a psychotic Pokémon clone who wants to be a Pokémon master, feels basic and dated. But it’s the central theme of the film, that fighting is futile and immoral, which feels especially jarring.

Scenes in which the Pokémon clones fight each other are accompanied (at least in the US version) by a cheesy pop ballad where the singer asks, “What are we fighting for?” Well, you’re fighting because that’s precisely what the whole franchise is based around. As characters line up to lament how “fighting is wrong,” it comes across as pointless mawkishness. This is downplayed in the original Japanese version, but tweaks made by US distributors exacerbated it for an international audience.

In fact, that’s not the only aspect the US distributors altered to the film’s detriment. In Japan, Mewtwo was given a lengthy backstory where he befriends other Pokémon clones who are promptly taken away by the scientists that made them, provoking his villainous rampage. US distributors worried that viewers wouldn’t want a sympathetic villain, so scrapped it. In doing so, they lost a large part of that character’s motivation for wrongdoing. There was also concern that young viewers wouldn’t want to wait 20 minutes for their first glimpse of Pikachu, so a vignette called Pikachu’s Vacation was shoehorned onto the start, which does little more than prolong the film’s running time.

The film has another fatal flaw – it’s not only an adaptation of a game but a TV series. Supporting characters that serve a purpose in the cartoon series don’t have much to contribute here, other than simply propping up and agreeing with the main character. Case in point: the villains of the series, Team Rocket, aren’t the villains of the movie, and consequently their roles feel a bit tagged on. Ash’s pals Misty and Brock feel equally superfluous.

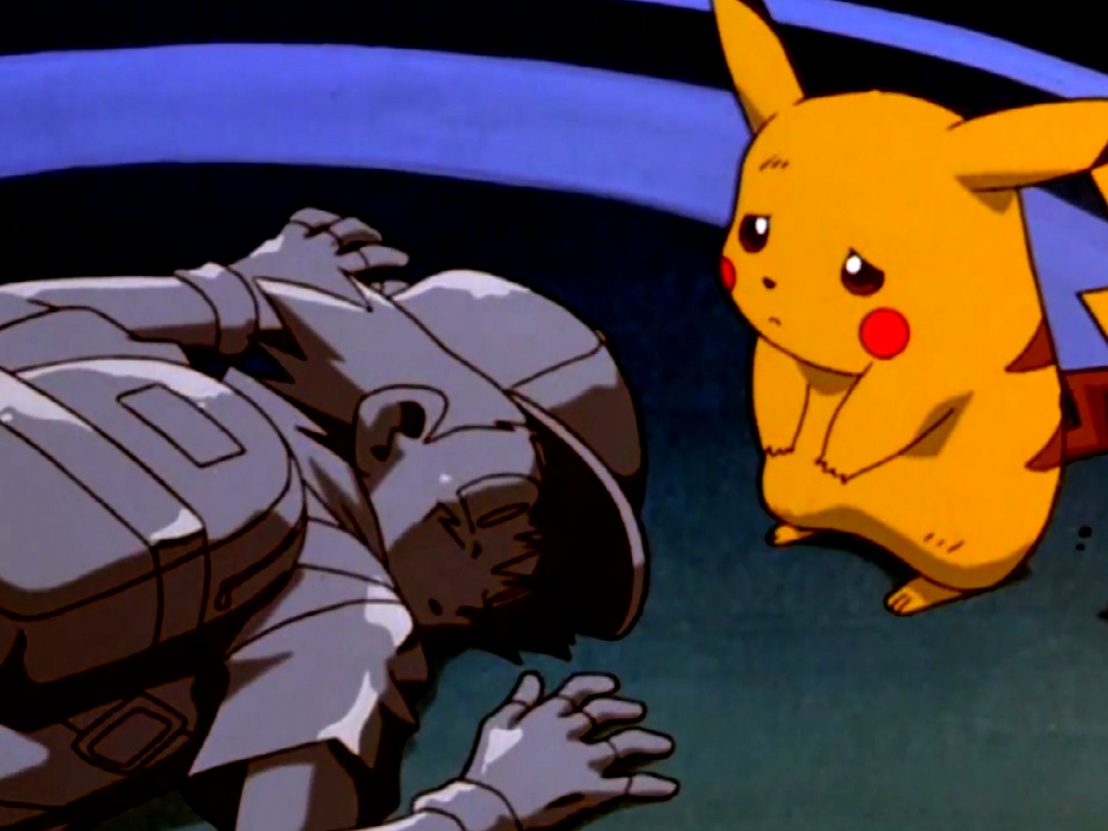

Towards the end of the film, there’s a scene where lead character Ash gets caught in the crossfire between sparring clones Mew and Mewtwo, and is turned to stone. All the Pokémon, especially Pikachu, are distraught by this – but fortunately their tears bring him back to life and all is well again, status quo restored. It’s a fairly inoffensive moment which serves to highlight a fundamental difference between storytelling in film and video games.

In games, death is not “game over”. You simply respawn and begin again. Characters don’t die, they expire or faint,only to be revived like virtual Lazaruses moments later. Characters in film with this power over mortality are rare, as without death their actions have few consequences. There’s no jeopardy, no peril, and it often makes for a tedious story. Despite this, Pokémon: The First Movie was a huge success. It remains the highest-grossing anime at the US box office, and in France and Germany it’s the highest-grossing Japanese film ever.

With the arrival of Detective Pikachu, it’s interesting to see the franchise moving in a different direction, rebranding itself for a new generation. Pokemon’s first film might be riddled with inconsistencies, but for anyone who was 10 years old in 1999 it was the cinematic event of a generation, and as such it’s stranger that it has been largely forgotten. If Detective Pikachu wants to be more than just a flash-in-the-pan hit, it would do well to take heed of its predecessor and shape its storytelling accordingly.

Published 4 May 2019

By Greg Evans

This curious ’90s phenomenon brought us animated versions of everything from Beetlejuice to Men in Black.

Ryan Reynolds voices everyone’s favourite electric yellow rodent in this fun, fast-paced murder mystery.

By Greg Evans

Between them Batman & Robin, Spawn and Steel pointed the way forward for the genre.