A lot can change in 20 years, especially in cinema. Take the superhero genre for example. Today it is a colossal enterprise, with connected universes expanding at an eye-watering rate. Given the richness of available source material it is remarkable that these monolithic blockbusters often feel so uninspired and lacking in diversity. Back in 1997, a trio of superhero movies were released which, despite their many flaws, were arguably much more progressive than their 21st century counterparts.

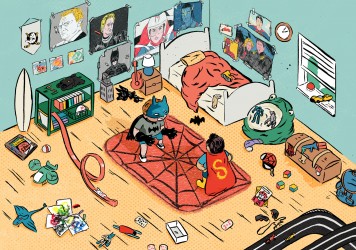

The most notorious of these is Joel Schumacher’s Batman & Robin. The director’s second Batman film, quickly commissioned following the box office success of 1995’s Batman Forever, has more in common with Mardi Gras than the gothic grit of Tim Burton’s earlier instalments. A combination of cringeworthy jokes, garish sets, rubber nipples and codpieces turned Schumacher’s film into a multi-million dollar laugh stock. Indeed, George Clooney and Chris O’Donnell have since admitted their regret at being involved in the project. The financial returns were so poor that Warner Bros cancelled several proposed sequels and the Caped Crusader did not return to the big screen until 2005 care of Christopher Nolan’s acclaimed reboot.

Yet Batman & Robin should be celebrated on some level. Apart from a mostly forgotten Supergirl movie from 1984, a big-budget superhero movie had never featured a prominent heroine. Batgirl, played by Alicia Silverstone in the 1997 film, is far from a exemplary female character but hers is possibly the strongest arc in Batman & Robin. The film also paints her as a much more intelligent individual than her Gotham comrades. The X-Men and Avengers movies would later improve upon these humble foundations – and it remains to see what Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel will bring to the table – but Batgirl’s contribution, although small, should not be disregarded.

With one of the most lauded and dependable superheroes falling spectacularly at the first (okay, third) hurdle, the next big comic book movie of 1997 faired little better. In the 1990s Spawn was easily the most popular non Marvel or DC character. Created by Todd McFarlane, Spawn is a CIA assassin who is wrongfully murdered and sent to hell only to forge a Faustian pact where he agrees to serve the underworld just so he can see his wife again. Admittedly the Spawn story is a little confusing, and its blockbuster adaptation certainly did little to make up for that, opting to overdose the audience on the most shoddy special effects to ever grace a $40m movie.

It’s hard to find much to praise in this quagmire of incoherence, but Spawn does hold at least one commendable accolade: it was the first major studio superhero film to cast a black actor in a leading role. Michael Jai White, who plays Spawn, clearly has a lot of respect for the source material and tries to bring as much gravitas to the role as the script allowed. White’s performance marked a welcome departure from the norm and in part set a precedent for 1997’s next superhero movie.

When it seemed as though things couldn’t get any worse for superhero fans, Steel happened. Starring NBA superstar Shaquille O’Neal, the film was based on a DC character who wears a technologically-enhanced suit of armour and wields a huge hammer. That’s about as interesting as our hero gets in this drab, unambitious and overblown TV movie, which is not remotely enjoyable. Steel was a colossal flop, earning just over $1m at the box office and effectively bringing a premature end to Shaq’s acting career.

Still, Steel does have its saving grace in the form of Annabeth Gish, who plays Susan Sparks, a wheelchair-bound woman who assists Steel in his fight for justice. Even though the film is ridden with clichés it does not dwell on her disability. She is simply shown as an intelligent and talented person who helps a friend in need, and in return is treated as an equal. It’s this positive representation of disability that sets this otherwise abysmal film apart.

Overall 1997 was a disaster for superhero movies, it took nearly five years for the genre to completely recover. In that period both Blade and the first X-Men movie were released, launching two successful franchises featuring black actors, both male and female, as prominent heroes. Fast forward to 2017 and we have Cyborg in the Justice League, plus Falcon and Black Panther in the Avengers, albeit in supporting roles. Disabled parts are still limited but Patrick Stewart’s seven-film run as Professor X proved that there is more than enough longevity for a disabled character if portrayed in the right way.

Twenty years ago, superhero movies were truly awful – but in their own way, they took the fledgling genre in a bold new direction. Things have undoubtedly improved, but it’s important not to forget that these three films pushed more boundaries than they were given credit for.

Published 2 Apr 2017

By Tom Bond

Roger Corman’s unreleased 1994 film The Fantastic Four was doomed from the start.

Twelve writers pin their colours to the tentpole in our survey of the best summer movies of the modern era.

From Guardians of the Galaxy Vol 2 to Wonder Woman, we preview the biggest new movies coming your way.