“Oh Luke, you wild, beautiful thing!” exclaims Dragline (George Kennedy), loving best friend to Paul Newman’s eponymous nonconformist. When Lucas Jackson is caught drunkenly pulling parking meters off their poles he is sentenced to two years in a Florida penitentiary. It’s an unforgiving place under the perpetual watch of the ironically nicknamed ‘the man with no eyes’, Boss Godfrey (Morgan Woodward), who stares down at the prisoners through his mirrored aviator sunglasses. It’s a place built on rules, both the internal regulations of the prison and the unofficial code of its unruly chain gang, who toil away under the hot southern sun.

Luke is a man who operates on his own terms. He laughs heartily as the police arrive to arrest him for petty damage to municipal property, and is willing to risk everything to escape what would have only been a two-year jail term. Newman’s exquisite portrayal of this nuanced character is a big part of why the film has endured for half a century.

Newman gives a masterclass in understated acting here. Luke’s presence shouldn’t really draw the attention of the audience and his fellow prisoners; he’s quiet and by no means walks with the confidence that his facial expressions betray. In his first few days in the prison he doesn’t assert himself in any considerable way. He is neither the new trouble maker nor the gang’s next leader, in fact a small comment gets him into a fight which he loses miserably and sees him slump back to his bunk defeated. So, what is it about Luke?

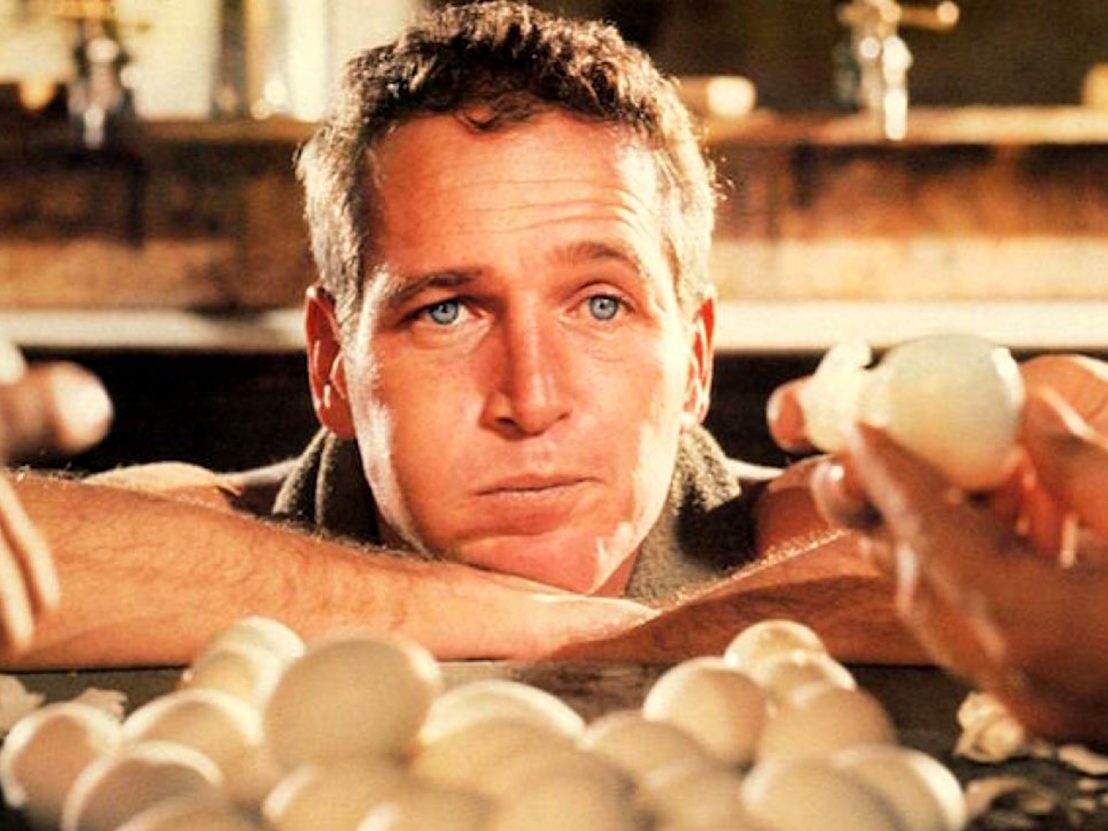

Scything crops shirtless in the punishing Florida heat, Newman’s physical presence does a lot of the talking for him. Luke draws in the gang with his quiet confidence, winning a hand of poker with a “handful of nothing”, after which he earns the nickname ‘Cool Hand’, and famously asserting that he can eat 50 eggs in one sitting, winning him both money and trust within the group.

The quiet charisma and uncrushable spirit that Newman brings to the role of Luke draws the prisoners to the newcomer and they soon grow to rely on his courage for their own strength and sanity. In this sense, Luke has been likened to the figure of Christ. In fact, Frank Pierson specifically wrote in religious symbolism when re-working Donn Pierce’s original novel into the screenplay. Luke is not the biggest or the strongest of the inmates, but he exudes assuredness through his actions.

He motivates the gang to work faster so they can enjoy two hours of blissful rest before the sun sets and he faces his unjust punishments with bravery. Donning a white robe as he is placed into ‘the box’, a small shed with barely room to move, he faces his punishment calmly. With his every attempt at escape, the prison population celebrate his freedom. “We in here diggin’ and dyin’, he’s out there livin’ and flyin’”, beams Dragline as he pours over a photo of Luke living life out in the free world. “That’s my baby!” his adoring disciple exclaims. Luke’s fellow prisoners look to him for guidance and hope and, in an uncanny biblical echo, begin to lose faith in him when his harshest punishment brings him to his knees and he begs the guards for mercy.

According to critic Roger Ebert, the film’s secret ingredient is Newman’ unmistakable smile. It’s a look of rebellion, of defiance and of the wicked enjoyment of subverting the rules that has both the audience and characters under its spell. At the time of the film’s release, the closing montage of Luke’s cheeky grin was an emotional climax to a fictional story. For a modern film audience, Cool Hand Luke is the perfect way to (re)discover both a brilliant actor and a beautiful man.

Published 26 Nov 2017

By Mayukh Sen

Sidney Lumet’s The Morning After sees the acting icon at her brusque, contradictory best.

Arthur Penn’s seminal crime thriller owes a lot to the likes of Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut.

Nick Pinkerton gauges the cultural impact of the clean-cut all-American icon.