Anyone tasked with writing about the work of filmmaker Patrick Wang will inevitably feel a degree of panic once putting pen to paper. Similar feelings might befall first-time viewers of his films; the singular confluence of genres, tones and formal rigour found in Wang’s work can initially be jarring.

Each work is so effortlessly dense, experimental, inventive and emotional that it’s almost impossible to do them justice with mere words alone, or a single viewing. This isn’t even my first attempt to do just that and I’m feeling nervous. Still, if Wang’s films have taught me anything, it’s that the fear and anxiety we feel about any major life challenge – be it creative pursuit, transition, or tragedy – is a process worth embracing.

Not surprisingly, Wang’s films exert such a profound impact precisely because of the various ways in which they depict our instinct to resist change, both individually and collectively. His 2011 film In the Family is an especially moving example of such a complicated, thorny situation.

At the time of its release, the film became something of an indie sensation after receiving a rave review from Roger Ebert. But there wouldn’t have been an Ebert review if not for the stalwart work by online critics like Rob Humanick of Slant Magazine, and the support of events like San Diego Asian Film Festival, both of which provided the film a platform to gain a wider audience.

Thankfully that’s exactly what happened, which considering the film’s length (3 hours) and director’s lack of name recognition makes it even more of a modern miracle. Looking back though, I’m hard-pressed to think of a more important American debut film in the last decade. In the Family revolves around Joey Williams (Patrick Wang), a successful contractor who lives with his partner Cody Hines (Trevor St John) in the American South. Together, they have raised Cody’s biological son Chip (Sebastian Brodziak) for the last six years in a home of relative happiness and fulfilment.

This all changes when Cody is tragically killed in a car accident. In the weeks that follow, Joey suffers a double tragedy of sorts when Cody’s sister claims guardianship over Chip, revealing the various inadequacies of a legal system that doesn’t understand or protect non-traditional families. Using long takes with static camera set-ups, Wang stages one stunning dialogue scene after the next, giving his actors space to bring the full weight of this human conflict to bear.

Sometimes memories of the past interrupt these moments, flashbacks that seem to be living alongside the action instead of separately. In the Family culminates in a nearly 40-minute deposition scene that remains one of Wang’s finest achievements, and perfectly symbolises the hope he sees in humanity, and our ability to transcend the fear that can easily ravage a family (or community) if unchecked.

2015’s The Grief of Others, which Wang adapted for the screen from Leah Hager Cohen’s novel of the same name, is an even more devastatingly raw example of this faith in our emotional capacity to endure. The broken family at the centre may live under the same roof, but each feels resolutely alone in life. Ricky (Wendy Moniz) has just experienced a traumatic pregnancy that resulted in the death of her baby, of which all the particulars she kept from her husband John (Trevor St John) until the last minute. Their two children – bullied teenager Paul (Jeremy Shinder) and sprightly tween Biscuit (Oona Laurence) – are both experimenting with modes of self-expression that could be destructive.

Adopting an even more avant-garde approach than In The Family, Wang upends all sense of linear temporality by presenting a fractured narrative that’s always on the cusp of collapsing. Once again, flashbacks seem to appear out of the ether, conjured by ghosts to remind of the festering traumas that must be confronted. Heavy guilt weighs on these characters to the point that the film itself begins to reflect their splintering selves in through aesthetic means. The use of superimposition, iris shots and varying film speeds show the diversity of Wang’s stylistic interests, and yet, each feels of a piece with this intimate exploration of loss and renewal.

While less emotionally gutting that his previous two films, Wang’s masterful 2018 diptych A Bread Factory Part I: For the Sake of Gold and Part II: Walk With Me a While are no less impressive, and reveals a filmmaker whose lofty ambitions and love of cinema has only just begun to scratch the surface.

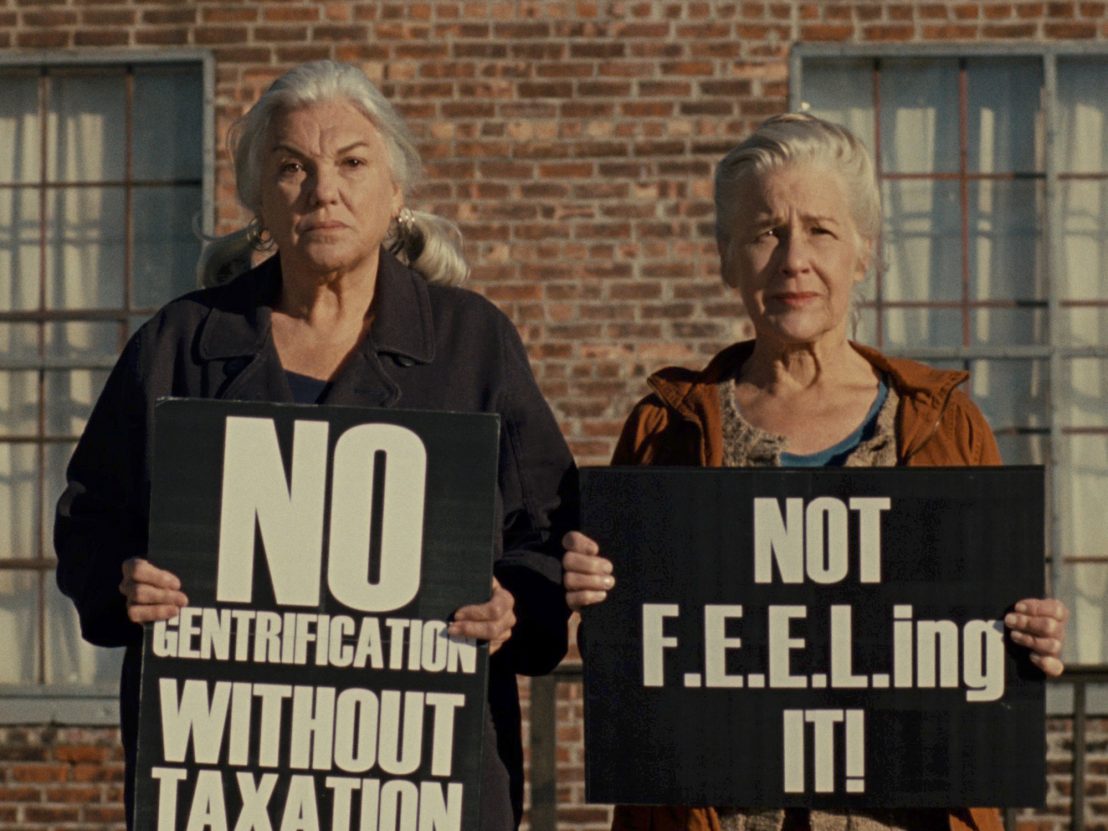

Set in the fictional upstate New York town of Checkford, the films grapple with corporatization of art, how local politics can be manipulated and the essential role of print journalism to cover it all. If the film has lead characters, they are immovable couple Dororthea (Tyne Daily) and Greta (Elisabeth Henry), devout proprietors of the legendary local arts space that has become the flashpoint for a city council vote over education funding. But this film really belongs to the collective of ornery filmmakers, passionate actors, discerning critics, supportive business owners, grumpy eccentrics, and precocious kids who make up Wang’s double shot mosaic.

For my money, the most pivotal scene takes place between the tenacious newspaper editor (Glynnis O’Connor) and her naïve intern Max (Zachary Sayle). She’s just called him out for quoting a press release in his puff piece on the town’s latest attraction: a fraudulent and corrupt post-modern performance artist duo named May Ray. As the teenager slowly realises the extent of his betrayal to journalistic ethics, she earnestly comforts him by saying, “Don’t run away from this moment.” In one way or another, all of Patrick Wang’s films embody the wisdom and empathy of this statement with every fibre of their cinematic being.

The films of Patrick Wang are in UK cinema from 18 Feb and on demand in March.

Published 16 Feb 2022

Rotterdam International Film Festival offered a rich programme in its second virtual edition, with intriguing sidebars on two vastly different artists.

Nestled amongst the sego palms and surfboards of southern California stands a living, breathing shrine to physical rental culture.

By Kate Jackson

Talented filmmakers like Desiree Akhavan and Ingrid Jungermann are making their voices heard.